March 22, 2021

Marty Walsh is undefeated when his name has appeared on ballots in Boston. By our count he’s 22-0. Not too shabby.

But there’s an asterisk involved: He did, technically, come in third in his inaugural election day effort.

Confused? Well, buckle up. A strange thing happened on the way to Walsh’s first-ever victory in March 1997 when he, then 29, won a six-way race to fill the vacant 13th Suffolk state rep seat held by Savin Hill’s Jim Brett.

But the March 1997 special election was not Walsh’s first effort to replace Brett, who had announced his plan to leave his seat vacant the previous September. Walsh, and several other would-be successors, first sought to “beat” Brett during the November ‘96 general election by using stickers.

It was an awkward political dynamic. Brett, who had run for mayor and lost to Tom Menino in 1993, was a popular figure in his district. But once it became apparent that at least one candidate— Neponset’s Charlie Burke— was intent on seeking to win the seat outright using a sticker/write-in campaign, everyone else in the field followed suit. All, that is, except a political newcomer, an assistant district attorney in Middlesex County, who had just recently settled on Pope’s Hill, and who ended up urging her supporters to vote for Brett. Her name: Martha Coakley.

In one sense, the sticker campaign didn’t work out for those who participated. Brett, who had already moved on to lead the New England Council, piled up 4,144 votes, in large part because his name was the only choice on the ballot for the state rep’s seat. In second place: “Blanks” with 2,896. Marty Walsh was next in line with 1,953, well ahead of the fourth-place finisher, Charles Tevnan, an attorney rooted in Ashmont-Adams who managed to get 847 sticker or write-in votes.

Despite coming up short, Walsh showed considerable organizational strength in his rookie electoral outing. He blew away all other hopefuls in his home base precincts in Ward 13, where he was born and raised. But he also won in Ward 16, which included precincts in Neponset, Fields Corner, and the St. Mark’s Area. It was a signal to his supporters and rivals that the fresh-faced, red-headed baseball coach was more than just a contender. Suddenly, he was a front-runner for the special election that would no doubt come next.

In the first week in January, the Speaker of the Massachusetts House— Mattapan’s Tom Finneran— set the date of the special election to fill Brett’s seat: Tues., March 11. It was going to be a sprint, but the field that had taken form months earlier was still largely intact. In addition to Walsh, Burke, Coakley, and Tevnan, there was another young attorney, James Hunt III, who could mine from deep political and civic veins in Neponset. Hunt had served as chief of staff to state Sen. Paul White, who then represented the area and was a beloved figure. Another candidate, Ed Regal from the St. Mark’s area in Ward 16, also joined the fray.

Another compelling candidate was Rosemary Powers, a well-known civic figure in Columbia-Savin Hill and a vocal proponent of toughening Boston’s residency requirements. She and Walsh were seen as rivals and shared a base in Ward 13. Her husband Coleman had replaced Walsh as president of the influential Columbia-Savin Hill Civic Association the year before.

Powers was impressive — she went on to run state Sen. Jack Hart’s office, served as a key aide to Gov. Deval Patrick, and now runs the Cristo Rey School in Savin Hill. She and Walsh would’ve carved up the Savin Hill vote to devastating effect for each candidate.

But on Jan. 9, she withdrew from the race and threw her support to Walsh telling the Reporter: “I’m going to work hard for Marty. I’m going to ask people I know to do the same.” Walsh told us: “It’s nice to have. I welcome her support. I have to go out and touch every vote. I’m going to try to outwork everyone else.”

He and his campaign manager, Michael McDevitt, could now stop worrying as much about an internecine fight among Savin Hill’s tightly packed three-deckers.

As I wrote at the time: “Now that Walsh is the sole master of Ward 13, he can pour all of his considerable support into the breach while the six Ward 16 candidates chew each other up.”

But the field of possibles was not yet done contracting. Barry Mullen, a St. Mark’s Civic Association leader who had toyed with a run himself, decided not to after Powers made her exit, throwing his support to Hunt, saying: “ I feel he’s doing it for the community and not for his own personal gain.”

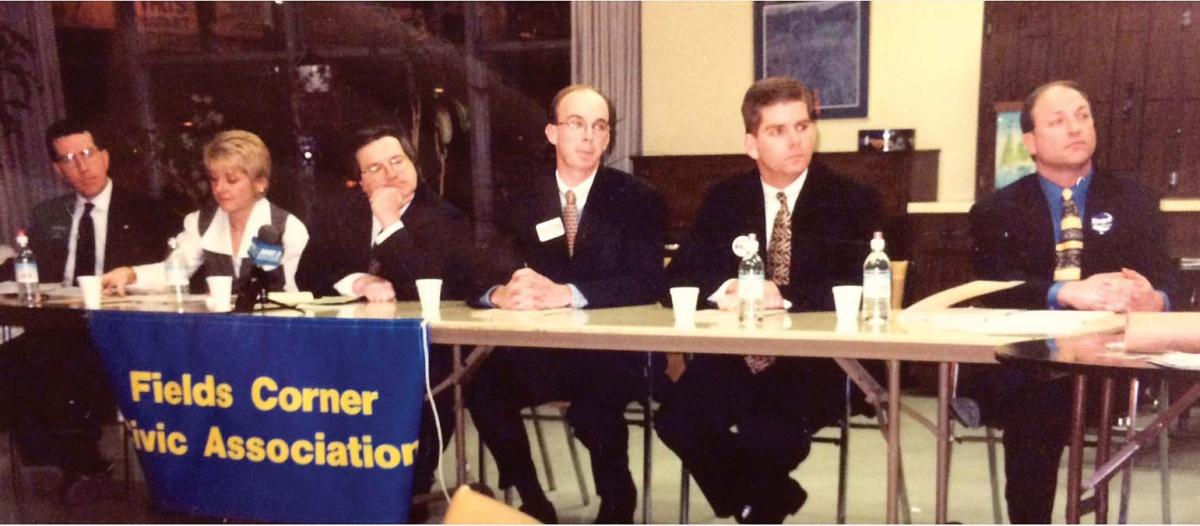

The candidates for 13th Suffolk state representative were shown during a candidate’s forum in Fields Corner in Jan. 1997. From left: Charles Tevnan, Martha Coakley, Charlie Burke, James Hunt III, Martin J. Walsh and Edward Regal.

After the first of several candidate forums on Jan. 28 in Fields Corner, the Reporter’s front page trumpeted: Fireworks Begin in 13th Suffolk Race.” Walsh, recognizing that the contest would likely be a two-man race between him and Hunt, targeted his rival directly for not having a public safety plan. “I have the guts to put it in writing,” Walsh told him.

Hunt fired back: “I don’t have paid people writing for me and developing those plans.” He sought to exploit the opening, describing Walsh’s resume as “vague,” adding, “after four months of campaigning against you, I still don’t know much about you.”

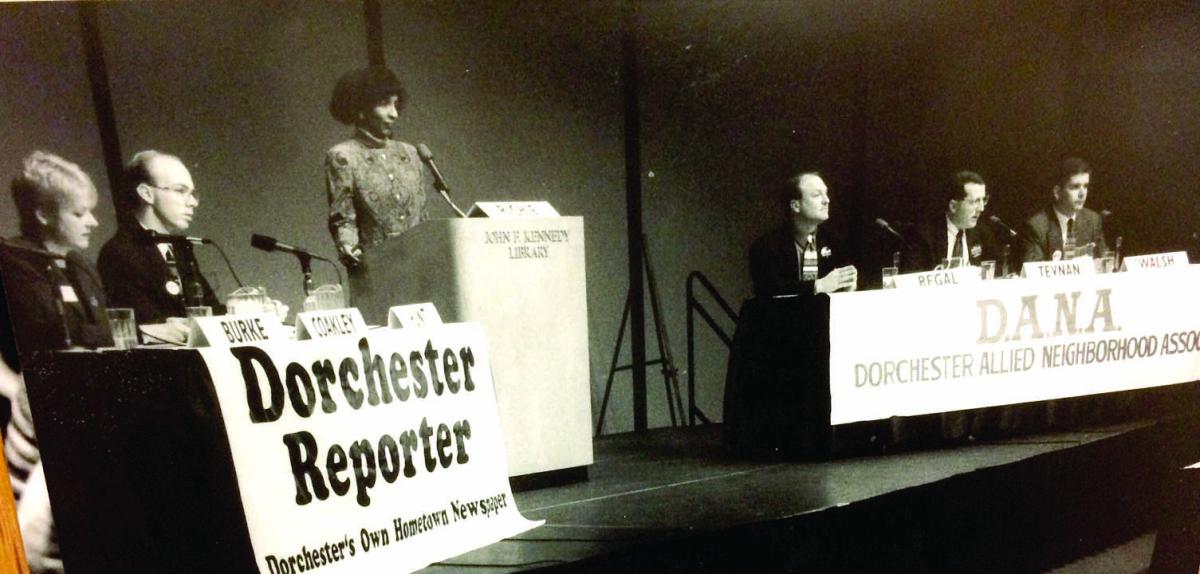

On Feb. 24, two weeks before the primary election that would decide the outcome among the all-Democrat field, the Reporter staged a debate at the John F. Kennedy Library. I was a panelist — and timekeeper—along with John Krall, president of the now-defunct Dorchester Allied Neighborhood Associations, and Jose Duarte, the principal of the Grover Cleveland School. Rep. Charlotte Golar-Richie, who would one day compete with Walsh for mayor, was the moderator.

The debate stage at the Kennedy Library on Feb. 24, 1997. From left: Martha Coakley, Jim Hunt, State Rep. Charlotte Golar-Richie, Ed Regal, Charlie Tevnan and Martin J. Walsh.

More than 400 people packed the Stephen Smith room for a 90-minute program that began with one of the six candidates, Charlie Burke, using his opening statement to withdraw from the race. (I was so stunned that I neglected to grasp the moment and rang a bell midway through his speech, not realizing that he’d be exiting stage left momentarily.)

Burke added intrigue to the moment by revealing that his own polling data revealed that it was a two-person race and he was not in the mix. “In this race, while I’m many people’s second choice, you run to win, not to come close.”

While he did not explicitly back any other candidate, Burke’s exit was widely seen as an assist for Hunt, who was gaining traction as the number of dawns before election day could be counted on two hands.

The rest of the debate was substantive and, at times, testy, with most everyone challenging Walsh with tough questions. “I wish Charlie Burke were still here,” Walsh joked at one point.

Hunt targeted Walsh for using an expensive hired consultant, Worcester Mayor Ray Mariano, to help direct his election, but Walsh was ready: “I, unfortunately, don’t have an elected official helping me,” he rejoined, a reference to Sen. White.

The ascendant nature of Hunt’s campaign was again underlined when Tevnan noted that the 24-year-old, youthful-looking law student “lives at home with his parents.” It was a line that elicited more than a few groans for Hunt’s loyalists in the room.

Walsh finished the night still in control, but with a resurgent Hunt, buoyed by Burke’s exit, gaining steam. A pre-election night rally at Florian Hall gave the rival camps a chance to flex their strength, and it was clear that the blue and red Hunt signs and the white and red Walsh signs would be the story the next day.

Election day turnout was steady throughout the day, but particularly strong in Walsh’s Alamo— Ward 13, precinct 10, St. William School on Savin Hill Avenue, where he could count on a lopsided margin and a gauntlet of poll workers led by Danny ‘Budso’ Ryan, one of Walsh’s closest allies throughout his career. He ended up with 436 votes at 13/10 on his way to winning 69 percent of the vote in Ward 13.

In Neponset, Hunt’s forces countered by pulling 75. Or so volunteers off the polls and sending them door-to-door onto the side streets of St. Ann’s parish to track down and drag out his “ones and twos,” campaign jargon for voters who had been identified as committed to or leaning towards a candidate.

It wasn’t quite enough, though. When the clock struck eight and the first Bud Lights cracked open, the results quickly showed a Walsh edge. The unofficially tally was Walsh 2,085 and Hunt 1,839. Tevnan was strong with 1,039 votes. Martha Coakley, who would go on to become the state’s attorney general, was a spoiler of sorts, plucking another 716 votes, mainly from Neponset precincts. Eddie Regal rounded out the field with 612.

In context, Walsh had barely survived. He grew his total from the November sticker campaign by a less than a hundred votes. To this day, some of Hunt’s stalwarts say that another week would have changed the outcome.

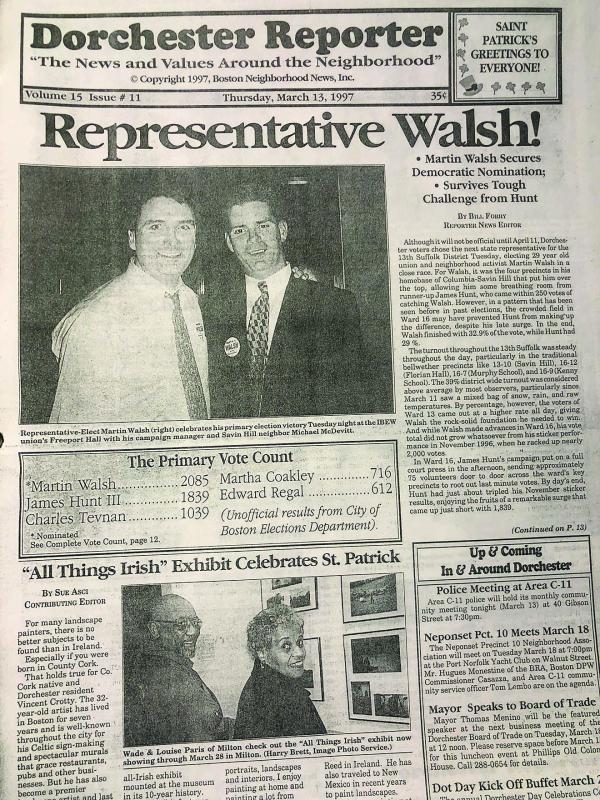

But the numbers didn’t take the edge off the sweetness of victory that night. Walsh gathered at the IBEW Union Hall on Freeport Street with several hundred supporters, many of them fellow laborers from the 223 local that his dad, uncle, and assorted cousins controlled. Stae Sen. Stephen Lynch and Rep. Jack Hart came by to congratulate him. Also in the crowd: one of his sandbox friends and super-volunteers, Annissa Essaibi, destined one day to win an at-large council seat and launch a campaign to succeed Walsh as mayor.

“I’m very happy and proud of the campaign we ran,” Walsh beamed. “Everybody who helped me conducted themselves in a classy way.” He added: I look forward to working with all of my ex-opponents. As we said before, we’ll all be friends.”

On April 11, Walsh cruised to his second election victory as the unopposed Democratic nominee for state representative. He was seated two weeks later.

He never lost a bid for re-election, and was only challenged once, in 2002 by a former supporter, Ed Geary, Jr. It wasn’t a contest.

Geary launched his campaign after it looked like Walsh would be leaving the Legislature. Secretary of State William Galvin had proposed that Walsh fill the vacant Registry of Deeds position, but after initially accepting Galvin’s offer, Walsh reversed course and decided to run for re-election.

At the time, he told the Reporter that he wouldn’t rule out running for another office in the future, saying, “I may still do that someday when the opportunity is right. Right now, I’m not done being a state rep.”