May 13, 2021

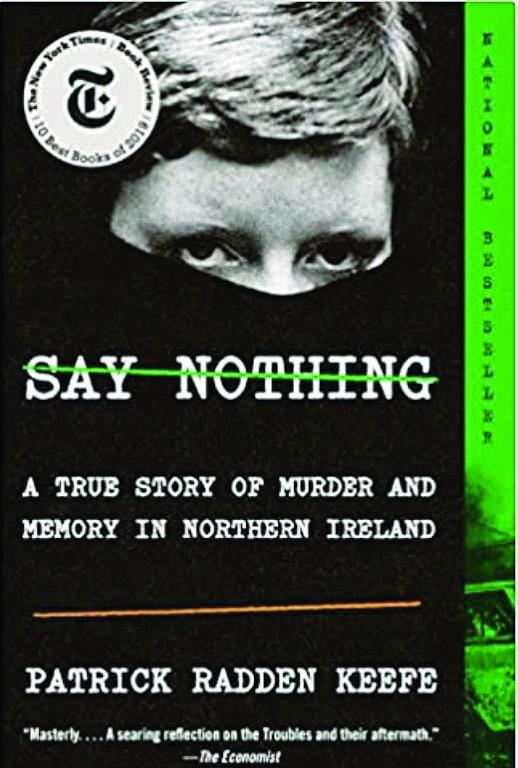

One of my rediscovered pleasures following vaccination is going into bookstores. A few weeks ago, I picked up Patrick Radden Keefe’s book “Say Nothing,” which is about “the Troubles,” the longtime conflict that turned violent in Northern Ireland in the late 1960s and lasted about 30 years. Keefe, who was raised in the Ashmont section of Dorchester, is a writer for The New Yorker magazine, and has published four interesting, award-winning books. He is an excellent writer, whose portrayal of “the Troubles” brought back many memories of my involvement with the Irish peace process, which stretched from 1999 to 2008, mostly through the Boston College Irish Institute and partly via a similar program out of Columbia University.

Following the Good Friday Peace Accord in 1998, the governments of Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the US funded efforts to bring Protestants and Catholics together in a peaceful way to build bridges between them. They looked for places that were not in Northern Ireland but would allow discussions of the causes of animosity between the parties while working on projects together. The Codman Square Health Center was one place that was chosen for those interactions.

Why the Codman Square Health Center, which was organized in 1974, the year the desegregation order was issued by Judge W. Arthur Garrity that resulted in school busing in Boston? The racial conflict that erupted following that decision was deeply felt in Codman Square where from the time of the banks’ “redlining” programs of the late 1960s, Washington Street was considered the dividing line between African Americans to the west and the mostly white residents to the east.

The organizing of the Codman Square Health Center in the middle of the busing troubles was one of the very few multi-racial efforts that succeeded in bringing people together for a common purpose.

Every nation on the planet has health centers, so the Catholics and Protestants of Northern Ireland could both understand the role of a health center in providing services, and see the results of an effort of residents living in a conflicted area doing something together. The American civil rights movement resonated with the people of Northern Ireland. The Catholics in identified with the movement and saw Martin Luther King as a hero. Protestants always referred to their summer marches as symbols of the claims to their civil rights.

So for several years, dozens of Protestant and Catholic participants in the peace process came to the Codman Square Health Center for several weeks at a time and worked alongside the health center’s medical, public health, and youth workers to perhaps learn how they could work together back in Ireland.

The Northern Ireland Peace Accord also involved the creation of nonprofit organizations (called Non-Governmental Organizations or NGOs there), and so my role, besides telling stories about Dorchester’s efforts to build a strong and unified community, was to teach things like fundraising and managing and supporting a diverse staff. It also involved my traveling to Ireland once or twice a year to participate in peace efforts there.

One chapter of Keefe’s book discusses the decision of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) to bomb sites in London in 1973 as a way to bring the civil war raging in Belfast to the capital of the UK. The bombing was organized by a division of the IRA called the Unknowns, which included one Gerry Kelly, who was in and out of prison for his IRA activities, who participated in the hunger strikes that became an international crisis for the British, and who later became a political leader in the Sinn Fein, the political arm of the IRA.

During one of my trips, which I think was in 2002, I was part of a group of four who traveled around Northern Ireland where we saw Protestant “Orangemen” march through a Catholic area (a few years later, I monitored a Catholic march), met with NGO leaders, and discussed community policing with municipal officials.

During that trip, the US State Department found out about it and asked us if we would meet with Gerry Kelly, who was described as “number three in Sinn Fein’s leadership,” to ask about Catholic participation in the police force.

Until 2001, the police force in Northern Ireland known as the “Royal Ulster Constabulary” (RUC), which by both name and effect was seen as an anti-Catholic paramilitary force. As part of the peace accord, the RUC was renamed the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), and an effort was made to desegregate it by recruiting Catholics. But Sinn Fein was refusing to endorse the PSNI, and Catholics wanting to be police officers were reluctant to go against Sinn Fein. The State Department wanted to know if this was likely to change, and made arrangements for the four of us to meet with Kelly, so we could ask the question.

The meeting was set up at a building called “The Felons Club,” a private place set up “to foster and maintain Irish Republican friendships formed during imprisonment or internment as a result of their service to the Irish Republican cause.” It had a bar, with a larger hall for events, but, because it was an IRA meeting place, it had extra protections built into it, such as cages that one had to go through to get into the building. You entered one chain link cage, which would lock behind you before you would enter the next cage, then you’d get to the entrance door.

After we entered, we were told that Kelly was busy and we would have to wait, and were ushered into the bar. As I remember, it was all men drinking beer, and so I asked for a Guinness and tried to ignore the tall man who stood uncomfortably in back of me. Our wait for Mr. Kelly continued and I needed to use the bathroom, so I left the bar area, followed by the tall man, who stood behind me in the bathroom. I turned around and asked the obvious question: “Are you following me?” to which he replied, “Yes, I am.” I thanked him for telling me, and we went back to the bar together.

After another pint of Guinness, we were told that Kelly would see us. We went into the larger room, where there were chairs set up for us in the middle of the hall, and introduced ourselves. After some small talk, we asked the State Department question: Will Sinn Fein encourage Catholics to join PSNI? He replied, “Go and tell your State Department that we’ll get there, but on our own terms and timeline.”

In 2007, the year of my last trip to Ireland on behalf of the peace process, Sinn Fein endorsed PSNI, and Catholics now make up about a third of the force. On my last night in Dublin, a group of us, including Boston Globe columnist Kevin Cullen, were having “pints” with the deputy chief constable of PSNI, who informed us that just a year or two earlier, he would have to inform the Dublin government that he was coming to Dublin so that they could meet him and give him an officer to protect him. But that was no longer necessary, as peace had broken out.

That same year, several former IRA soldiers told me that the war was over because Ireland was in fact united – through the European Union. But the new peace could be undone. The Brexit vote that resulted in the United Kingdom leaving the European Union has been problematic for Northern Ireland, and there have been signs of new troubles.

Peace requires continuous nourishment and hard work.

Bill Walczak lives in Dorchester and is the former CEO of Codman Square Health Center.