November 24, 2021

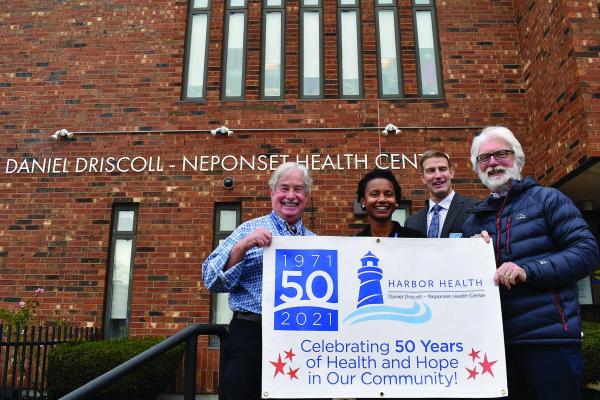

Pictured from left to right: Dr. Bob Hoch, pediatrician and former Chief Medical Officer of Harbor Health, Dr. Monera Wong, Chief Medical Officer of Harbor Health, Dan Driscoll past CEO and Chuck Jones, current CEO of Harbor Health. Photo courtesy Harbor Health

Fifty years ago, the newest face of health care in Dorchester was a line of mothers with baby carriages outside a storefront on Neponset Avenue.

If the patients at the newly opened Neponset Health Center looked like a throwback to a time when a medical visit was within walking distance, or even at home, they were also a sign that times had changed. Just one block away, Neponset Circle had become less a rotary than a shadow beneath highway traffic that was mostly going somewhere else. And, as area residents noted with dismay, the same thing was happening with local medical practices.

Just beyond the opposite end of Morrissey Boulevard, problems with access to care were already being addressed by a pioneering model at the Columbia Point Health Center. It was the first community health center in the nation, opened in late 1965 at the Columbia Point public housing development. Founded by visionaries in a struggle against racism and poverty, the center’s primary support was from federal programs advancing health care to address underlying social problems.

In the Neponset area, the concern was more straightforward: a lack of access to doctors, especially for residents of Port Norfolk, a waterfront neighborhood increasingly cut off from the rest of Dorchester by the Southeast Expressway’s opening in 1959. When a group of residents formed the Port Norfolk Health Committee, they sought help from Jean Hunt, a Neponset resident who was also a nurse at the Carney Hospital, the first Catholic hospital in New England, which moved to Dorchester from South Boston in 1953.

“Before people started moving out of the city, doctors lived and worked in the community. And, as they died off, younger physicians did move out, to the suburbs,” Hunt recalled, “so it was hard because we didn’t have access to care.”

For residents of Neponset and other parts of Dorchester, the alternatives were longer trips to medical practices or seeking outpatient care at hospitals—trips easier to make by car.

“That was a big problem,” said Hunt, “because in the late sixties and early seventies, people had only one car, and the breadwinner took the car.”

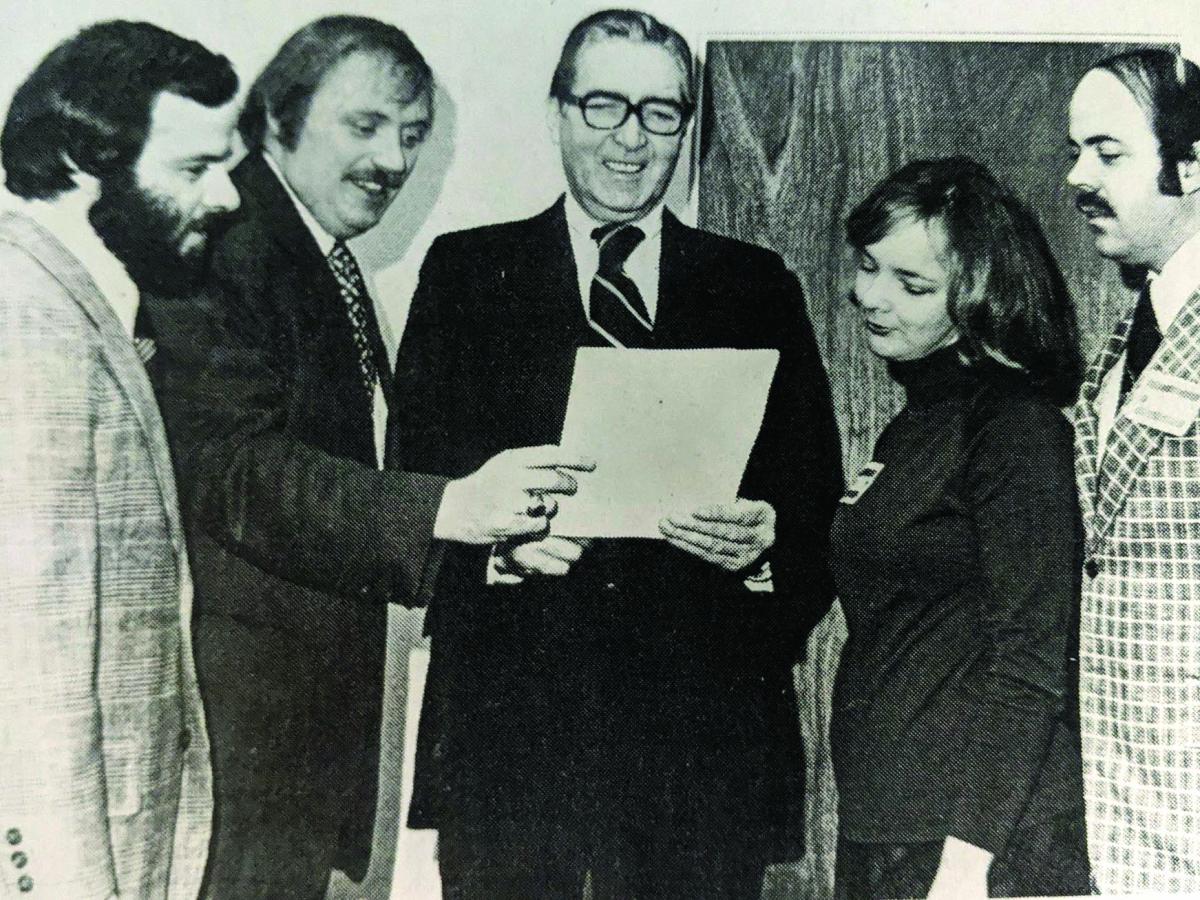

Pictured during a fifth anniversary event for the Neponset Health Center were,l-r, Jack Cross, administrator; Ed Forry, president of the health center committee; Edward Moore, administrative assistant to Congressman James Burke; Jean Hunt, vice president of the health center committee; and Jim Hunt, Jr., building committee chairman. Rep. Burke had secured a large federal line-item — $700,000— to help building the facility that now houses the health center on Neponset Ave. File photo by Steve Allen Sr.

That was also a problem for the Carney Hospital. According to Ed Forry, one of the health center’s early board members, the hospital’s emergency room was “being swamped” with patients who, just a few years earlier, would have been at a doctor’s office.

Along with supporting the Neponset Health Center, the Carney would play a role in the startup of other health centers in Dorchester and Mattapan, even holding their clinical licenses. And, when Forry came to the Neponset Health Center for his father’s first appointment, the nurse working the evening shift was one of the Carney’s future top-level administrators, Sister Kathleen Natwin, of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul.

“It cannot be underestimated,” said Forry, “how valuable the Carney’s role was in those years in getting things started.”

Forry and his wife, the late Mary Casey Forry, had one other claim to being health care pioneers, as parents of the first child served by the health center’s OB/GYN program—Bill Forry (the publisher and executive editor of the Dorchester Reporter).

The Neponset Health Center opened on a part-time basis in late December of 1970, thanks to help from the City of Boston, Permanent Charities, and funds raised from neighborhood Tupperware parties. The staff included two pediatricians from Carney Hospital and a nurse. There were four rooms, renovated with help from neighborhood residents, among them Hunt—who would become a chair of the health center’s board--and her husband, James W. Hunt, Jr.

“The health center provided not only a local option,” James Hunt said, “but also a private model that had a sliding fee scale, that ‘All are welcome here,’ that could provide comprehensive services. And, of course, some of the hospitals benefited from strong referral patterns between the health centers and those hospitals.”

Recruited from high school by Boston Mayor John Collins to work for the city, Hunt went from community volunteer to full-time advocacy with the Mass. League of Community Health Centers. He would work there more than 42 years, almost all of that as its president and CEO.

Less than six months after the health center’s opening, a conference took place at Northeastern University that would lead to the league’s formation. The meeting brought together representatives from 22 community health centers, as well as insurers and other providers. The object was to solidify a base for addressing common concerns: from reimbursement flow to a stronger role for consumers and a definition of care that went beyond medical treatment.

In 1977, the Neponset Health Center moved to its current location, in a new building at the former site of the Minot School. That required help from the city, but the largest amount of funding for the new facility—$840,000 — was from the federal government.

Dan Driscoll, former CEO of Harbor Health, Jean Hunt, founder and former president of Neponset Health Committee, Mary Lou O’Connor current board chair of Harbor Health, Chuck Jones current President and CEO. Photo courtesy Harbor Health

In the same year, Dan Driscoll became the health center’s administrator, after being recruited by James Hunt. Driscoll had spent a year at the Mass. League, after working as a city planner. He also had a master’s degree in planning from Cornell University, with a thesis on community participation at neighborhood health centers, including the one at Columbia Point.

When he started at the health center, Driscoll said, the staff had increased to 23 people, with an annual budget of about $400,000. What remained the same was a community board that helped make decisions about services and the overall mission of community health.

“One of the things we used to say at Neponset,” Driscoll explained, “is that the difference between a private doctor’s office and a neighborhood health center or community health center was that, for the health center, the community was the patient, not just the people in the waiting room.”

As examples of looking beyond the waiting room, Driscoll cited outreach efforts and services aimed at Dorchester’s growing immigrant populations from countries such as Vietnam and the Republic of Ireland. There would also be more attention to problems with mental health and substance abuse.

“We developed substance abuse programs because that’s what was going on, and it wasn’t in the waiting room,” said Driscoll. “And, in fact, there were people coming in for medical appointments and your ability to treat them was so compromised by the fact that they had all this other stuff going on.”

Driscoll described the approach as treating the patient holistically. And, during the 1980s, community health centers in other parts of Dorchester were also looking beyond the waiting room, especially to address the growing racial disparity in infant mortality.

According to a national leader on health care policy at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Dr. John E. McDonough, the difference in focus still applies to health centers around the country. Together with a dwindling number of safety-net hospitals, he said, they are “what remains of a mission-driven health care system focused on human and patient needs, not money.”

But financial need was a factor in the 1985 merger of Neponset Health Center with the Columbia Point Health Center, which was on the brink of receivership. The merger prompted formation of a new provider network, Harbor Health Services, where Driscoll would become president and CEO in 1994. Eventually expanding to five health centers and two inclusive care programs for the elderly, the network currently has a budget of $78 million.

The merger was the first in Boston between health centers. They served different communities but, as with the health center at Dorchester House—which also opened in 1970, they all were initially concerned with barriers to primary care, even if not always primarily caused by racial discrimination or poverty.

According to Driscoll, the merger changed the composition of the board, while the greater mix of patients allowed more programming and funding opportunities. And he said the continued growth of the Harbor Health network, with the Neponset Health Center being open 363 days a year, would add up to greater bargaining power, whether with insurers or other kinds of providers, including the Carney Hospital’s current operator, the Steward Health Care network.

“You can deal with Carney Hospital Daughters of Charity by just being a local health center,” Driscoll said. “You couldn’t deal with Steward, you couldn’t deal with Partners (HealthCare), you couldn’t deal with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, by being this little thing. You needed to meet their needs.”

As health care reform expanded access overall, the growth in risk created more opportunity for health centers. “And one of the beautiful things that happened,” Driscoll added, “is that the healthcare insurance companies finally accepted that certain amounts of preventive care would save money.”

As Driscoll and James W. Hunt, Jr. note, the size and mix of populations served by community health centers also mattered politically. The health center model hailed by a leading liberal in the US Senate, Ted Kennedy, at Columbia Point, could also be modified and embraced by what Driscoll described as the “bread-and-butter Democrats” of Neponset. As Forry put it, “People were starting a health center, not for the neighborhood, not for the person next door, but for themselves.”

But, by Driscoll’s reckoning, a multiple of that could easily have broad political appeal.

“A vote for a health center, cutting a ribbon at a community health center, voting for a health center appropriation,” he said, “became a smart thing for people politically, regardless of their political affiliation.”

Like other providers of its kind, the Neponset Health Center is described as an anchor for the community—as a place that creates traffic for neighborhood businesses, as a visible destination for patients, and because of how their mix over time reflects neighborhood change and continuity. The center currently reports serving more than 10,000 patients per year, almost two-thirds of them people of color, who also account for the majority of the staff.

In 2017, Driscoll’s contribution would be acknowledged on the exterior of the building, officially renamed as the Daniel Driscoll – Neponset Health Center. By that time, many health centers started by grassroots pioneers had become larger and more professionalized. But, as McDonough emphasized, they remain committed to serving anyone, regardless of income, health status, or citizenship.

“In a society still defined by racial and ethnic disparities and inequities,” he said, “they stand apart, in a good way.”

And Forry sees the notion of care as a right, which inspired the creation of health centers half a century earlier, as being affirmed on a larger scale in government response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Boston, health centers played a role in that response, with testing, food relief, and an expansion of telehealth services supported by the state.

“Whether we have a right to be healthy has been debated back and forth by conservatives and liberals,” said Forry. “And yet, when the pandemic came along a year and a half ago, there’s been no question.”