September 23, 2020

In November, Massachusetts voters will take up a ballot question that would fundamentally reshape the way they cast their ballots. Under a system called “ranked-choice voting,” elections that involve more than two candidates give voters the option of numerically marking their choices.

Proponents of ranked-choice voting (RCV) say it would help to ensure that no candidate is elected by a minority of voters. Supporters include former Govs. Deval Patrick and Bill Weld, as well as former Harvard president Lawrence Summers, who calls it “the single most important change we can make to improve American democracy.”

But the system is controversial. Those against the proposal say it violates the “one-citizen, one-vote” principle and could create a bureaucratic nightmare.

How Does It Work?

Ranked-choice voting only applies to races with three or more candidates, and only when one candidate does not reach greater than 50 percent in the initial vote tally.

Until that point, votes are tabulated at the precinct level, the same way they are under the current system. If no candidate gets more than half the votes, the ballots go to a central location where the non-first choices are redistributed in successive rounds until someone crosses the 50 percent threshold.

In each round of the counting, the last place candidate is eliminated, and the second choice of that candidate’s voters are added to the tallies of those who remain. That process continues until a candidate tops 50 percent.

If the ballot initiative passes, it wouldn’t be the first time voters in the state get to rank candidates. Cambridge has a system known as “proportional representation,” which ensures that “any group of voters that number more than one-tenth of the votes cast can be sure of electing at least one member of a nine-member Council.”

Why Proponents Want the Change

Those behind the ballot initiative say elections are broken. They point to candidates who win elections without majority support. One case is Massachusetts Congresswoman Lori Trahan, who among 10 Democratic candidates ran for the 3rd District House seat in 2018. She won the primary election with less than 22 percent of the vote.

Proponents of ranked-choice voting are now also citing Jake Auchincloss’ recent 4th District Democratic primary win. In a packed race, he won with less than a quarter of the vote.

“It has now become the exception, not the norm, for winning candidates to achieve majority support in highly competitive, widely contested races,” according to a press release from the non-partisan group MassVOTE. “Ranked-choice voting, however, can fix that.”

Voter Choice Massachusetts, the advocacy group behind the ballot initiative, estimates that 40 percent of races involving three or more candidates result in a winner who does not get a simple majority.

Those who champion the system say ranked-choice voting will spur greater participation in elections and encourage campaigns to reach out to a broader base of support, and thus lead to more civilized politics.

Maine, the First with RCV

Maine voters opted in a 2016 ballot initiative to become the first state to adopt ranked-choice voting for statewide elections. Proponents pushed for RCV after conservative Paul LePage won the governorship with a minority (or a plurality) of the vote — first in 2010 with 37.6 percent, then in 2014 with 48.2 percent.

Proponents characterize the effort as a non-partisan way to expand participation and allow more diverse candidates to get elected. But some conservative opponents, like the Maine congressman who lost his seat to RCV, argue that progressives are more likely to run multiple candidates in an election, drawing more voters to the polls who favor a Democrat over a Republican as a second choice.

The first major test of RCV happened in 2018 in Maine, over a House seat then held by Republican Bruce Poliquin. Poliquin got 46.3 percent of the votes in the first round — slightly better than his Democratic opponent, Jared Golden — with about 8 percent split between two independent candidates. Because Poliquin didn’t cross the 50 percent threshold, a second round of counting was triggered, and Golden pulled ahead with 50.6 percent to win the race. Poliquin tried to fight RCV in court but was unsuccessful.

Last month, the law survived the latest of several legal battles questioning its constitutionality. Maine’s Supreme Judicial Court recently blocked a ruling that would allow a ballot question to repeal RCV — the third time in four years that voters there would have had the chance to vote on the election system. Maine is now set to become the first state to use RCV in a presidential contest, though legal challenges remain ahead of the election that could change that.

Backers and Opponents

The group formed to push RCV here is Voter Choice Massachusetts. Supporters include the state Democratic Party, the League of Women Voters and the Massachusetts Immigrants and Refugees Advocacy Coalition. Financial supporters include prominent CEOs in Massachusetts, as well as advocacy groups Action Now Initiative and Unite America.

Voter Choice Massachusetts says it has raised $5.5 million as of mid-September, with roughly half of those funds raised in the two weeks after the Sept. 1 primaries.

The Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance has railed against ranked-choice, claiming the state would be better off with runoff elections. In runoffs, a field of candidates is narrowed to the two top vote-getters, and a second election is held to determine the winner.

The ballot committee against RCV in Massachusetts is called No Ranked Choice Voting Committee, which organized late in the summer. Patricia Chessa, chair of the Westford Republican Town Committee, is listed as the group’s only official, according to the Office of Campaign and Political Finance. Chessa did not immediately respond to a request for comment, and no data is available on the OCPF website.

More broadly, critics of the election system often say it is too confusing for voters.

What Would RCV Apply To?

Beginning in 2022, the system would be used in primary and general elections for statewide offices in Massachusetts, as well as certain state and federal legislative positions. Ranked-choice voting would not be used in presidential elections, county commissioner races, or district school committee races.

If approved by voters, advocates say the new system would be limited to these offices at first but could expand to other races, including the presidential election.

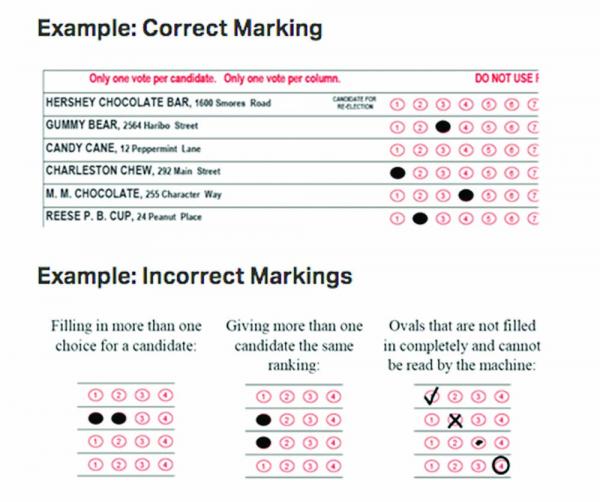

Should voters approve the ballot measure, the secretary of state would issue regulations as to the mechanics of RCV in Massachusetts and carry out a campaign to educate voters on the new process.

This article was published by WBUR 90.9FM on Sept. 14. WBUR and the Reporter share content through a media partnership.