June 4, 2020

At the farther end of life, my 78th year, I’m regularly prompted to cast my mind back to the long ago. Most often, it’s a name or place cited in the local news that triggers remembrances of family, friends, and associations from my boyhood time in Dorchester. The easy recollection of things that happened to me, and around me, when I was being guided into adolescence and Catholicism by my parents and my relatives, by the teaching nuns at St. Mark’s parish school, and by the Jesuit priests at Boston College High come into my memory accompanied by vivid colors and fetching voices that suggest those events as having been special, or blessed. Maybe not all were that way in the happening; still, specific names and faces and words attached to specific events during my growing-up years rebound with an unreal clarity 65 and more years later, even as other memories – the good, the bad, the indifferent – have vanished into the mists of time.

Pattie Anne and Sister Superior

In early April 1953, she was the last of the children of Tom and Julie (Harrington) Mulvoy to come home to Lonsdale Street from St. Margaret’s Hospital, following Mark, aka Skippy (’41), Tommy (”43), Bobby (’44), Mary (’47), and Jimmy (’49). I was fascinated by the tiny girl who had joined our busy five-room household. After a while, I began to take her for walks in her carriage, usually during school lunch time (At St. Mark’s, we were off from 11:30 to 12:55). She was almost always asleep on the way down to Adams Street and back.

The last time we took a stroll was just before noontime on June 3, when I handed her off to my mother. An hour or so later, Patricia Anne Mulvoy, aged 68 days, was found dead – “A blue baby,” I later heard a neighbor say, a reference of the time to the color of her lifeless countenance – in her carriage on our front porch by our upstairs neighbor and landlord, Anna Ford. As I walked down the street on my way home from school, the fire truck outside No. 22 was my first notification that all was not well at our house.

In the days that followed, the widespread chaos of grief in the wake of the horribly unexpected defies my ability to describe it 67 years ago this very week. There was a wake (“our tiny angel dressed in innocent white in this small casket,” said Father Dunford), a funeral, a burial, and, forever after, seven altered lives back at home.

Patricia Anne Mulvoy March 27-June 3, 1953

A few days after the services, I was at school when I was told by my fifth-grade teacher, Sister Isabel Mary, that “Sister Superior wants to see you in her office.” This was not ordinarily a welcome message. Sister Anthony of the Sacred Heart, SND, was a formidable personage who supervised a host of formidable teacher-nuns who lived in their convent across from the school. She answered the door when I knocked and asked me to come in and sit down.

For the next half hour, she was mostly a listener as she encouraged her 10-year-old pupil-visitor to say out loud what he was thinking about the previous week’s events. When I told her that I was angry at God “for taking my beautiful little baby sister away from us” and for making my mother “cry too much,” she leaned toward me and said softly, and in so many words, “Thomas, life will continue to challenge you with things you don’t understand and think you can’t handle, but you are family-rich and with them you will be okay. Trust me, and God bless all.” As I walked toward the door, she came over and gave me (appropriately for that time and place) a light hug. Her embrace startled me – surely, a Holy Cow! moment – but the warmth of her touch brought a soothing sense that I feel again as I type these words.

Charlie Paget, Maestro at Wainwright Park

He had been struck by polio as a boy, and the effects of the disease lasted more than 60 years – a curved back held steady by a sturdy brace that also pinched his lungs, making his every breath a chore. By the time I came to know Charlie Paget, in the early 1950s, he was about 40 years old and the longtime caretaker at Wainwright Park, a typical urban play space set in a square bounded by Melbourne, Brent, and Wainwright streets and, to the north, by a multi-family dwelling known as The Frederick. Charlie’s working status with the city’s Park Department, given his disability, was a matter of curiosity, but he acted to the max as if he were lord of the domain. Over seven days a week, he arrived at the small brick municipal building at 9 each morning and he stayed until 5. He then came back about 7:30 and stayed till 9 o’clock. In the wintertime, he sat inside all day and evening long; in the spring, summer, and fall, he worked outside, setting the white lines on the baseball diamond, sweeping the courts beside the main building, raking leaves and burning them in large piles scattered around the outfield; in general, keeping things as neat as he could in a mostly grassless place some called “Charlie’s Pebble Palace.”

Over time, especially toward the end of the decade, I joined a small number of regulars who enjoyed sitting with Charlie on the steps of his building until darkness closed down summery days. He was full of information about the neighborhood and its people going back to his childhood days when he was a schoolmate of my mother’s at the Emily Fifield School in Codman Square. He had detailed stories, and opinions, about the politicians who had helped govern the neighborhood since the high-gloss times of James Michael Curley and Honey Fitz. A fierce advocate of fiscal responsibility, and a Republican (gasp!), he could describe, in chapter, verse, and numbers, what he saw as the “folly” being set loose in City Hall and at the State House.

I remained a close friend of Charlie’s until his death in 1974 at age 76 just a week after I had taken him on a “one-last-time” day trip to Martha’s Vineyard, the site of his childhood family vacations. He was the perfect mentor for a boy who told him early on that he wanted to become a newspaperman. Charlie never missed an edition of whatever Boston paper he was enthralled with at the time; he knew the history of generations of newsmakers in Boston; and his eagerness to tell the stories of those people enhanced greatly my sure sense that I had chosen the right profession to pursue. It is still quite the ride after 55 years of reporting, editing, laying out pages, and composing headlines at two fine Dorchester institutions, The Globe (1966-2000) and the Reporter (2003-20??).

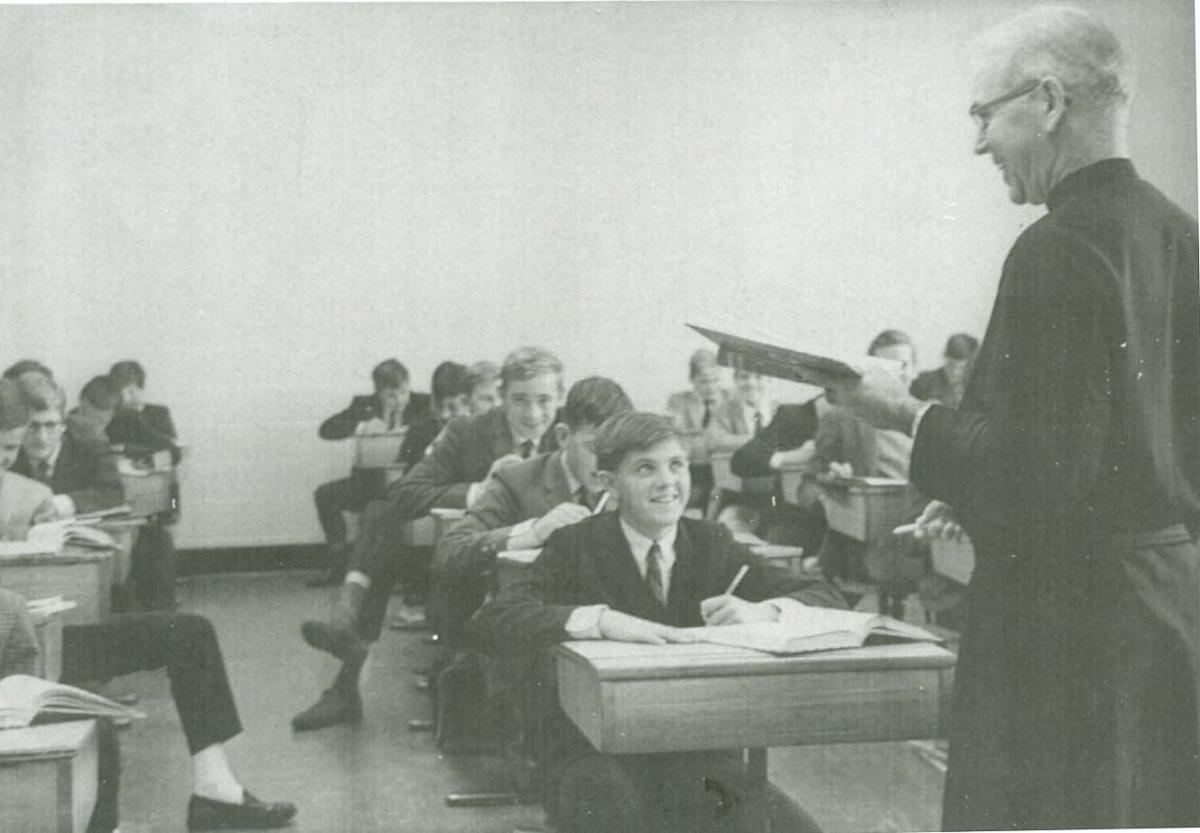

Father Sullivan and Gen. Marshall

The Rev. John Whitney Sullivan, SJ, was a son of Dorchester whom I first met in 1956, in Classroom 1L in BC High’s Loyola Hall where he taught mathematics to freshmen. White chalk in hand, he slowly unwrapped the mysteries of mathematics, his casual classroom manner and explanatory brio a decidedly new look from the way the sisters engaged with their pupils at St. Mark’s School. I kept in touch with Father Sullivan during my school time on Morrissey Boulevard and after graduation until his death in 2003, when I wrote his obituary for The Globe. In between there were regular lunches, which were easy to arrange because we worked across the Boulevard from each other. There also was a special occasion: He gave me the last rites in August 1964 when a perforated ulcer almost did me in.

Father John’s influence on me came with a bonus: He steered me to an avocation that has not wavered in interest since October 1959 when, for reasons I cannot recall, he mentioned to me one morning that “George Marshall has died.” I forget what my response was, but whatever I said, he was back at me later in the day with a copy of that day’s New York Times, which had devoted a large block of space and a photograph on the front page and an entire page inside to the obituary of the man and general officer who led the US Army throughout World War II, who set up the Marshall Plan that helped Europe recover from that catastrophe, and who, in 1953, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, an uncommon selection for a soldier. The bookcase in my home office that is filled with Marshall memorabilia is also a testament to how my best-ever teacher and friend whetted my appetite for history and the men and women who made it.

The Shamrocks, and Our Coaches

We three met (warily, I suspect) in Miss Dinn’s kindergarten class at the Elbridge Smith School on Centre Street at Dot Ave in 1948. In June 1956, we graduated from St. Mark’s grammar school. In June 1960, we took our leave of BC High, and in June 1964, we commenced adult life in Alumni Stadium at Boston College in Chestnut Hill. We were not joined at the hips, Jack Gallagher, Paul Sullivan, and I; we were good friends who by dint of our birthdates spent a lot of time with each other in school and out over close to two decades. We had many friends, close ones named Billy and Jack and Franklin and Joe, to cite a few, and we had a gang, of the benign sort, the Shamrocks, with Wainwright Park as our home base for games and for hanging out while our parents were at work. There were no class divisions in the Shamrock family; our home lives were alike, each in its own way.

Smiling teacher, smiling students: Father John Whitney Sullivan engages in math with his BC High students in the 1950s.

There was little organization to what we did at play (the pastor and our nuns warned us against fraternizing with the kids at the Y in Codman Square. (God knows what when on up there!) If we didn’t have enough players to fill all the positions for a baseball game, we set up “clear fielding,” where a hit to an empty right field was an out for a right-handed batter, and to left for a kid who batted from the other side of the plate. We also played pick-up games of basketball, stickball, roofball, and halfball, then sat on the courtyard wall to needle each other and share local teenage gossip.

By the late 1950s, we had coaches (I don’t know who asked them) who showed us the ways a team organizes to succeed, but not necessarily to win. There was the parish unit of the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO), where Father McGann was the chief priest and No. 1 fan. Bobby Reardon, later an Oblate missionary, drilled us relentlessly in engaging with the fundamentals of baseball; up at Girls Latin School on Friday nights, John Dooley showed us how to jab and clinch and counterpunch; Jimmy Kelly made calisthenics a part of our daily routines; Leo Smith, a large man with a loud voice and generous heart, made a basketball team out of a motley crew whose on-court talents ranged from “good” to “not bad” to “what’s a layup?” and George and Madeline Reardon organized a boys and girls CYO bowling league at the Lucky Strike Lanes in Fields Corner.

He was Bobby Reardon to The Shamrocks, but to his parishioners in Brazil later he was their pastor, Pe. Chico (Roberto Francisco Reardon), an Oblate father.

All of which speaks to the spirit of adult concern and generosity that underlay life in the village where I grew up. It’s the same drive that that is present in the neighborhood today with the organizers, benefactors, coaches, and players of community stalwarts like the All Dorchester Sports League and its emphasis on athletics, life skills, academic focus, and nutrition, and with the dedicated staff at the Boys and Girls Clubs.

Time and adult responsibilities have seen a dispersal of most of the friends of our youthful gang, some of them to places far away. But best friends are forever. The trio of 1948 is now two; Sully has died. Every time Jack Gallagher and I talk, every time we met for lunch or dinner before the coronavirus stopped that routine, the backdrop to our conversations – our Dorchester Days together in the long ago – reminds me that those memories – vacations in Winthrop, painting (poorly) the walls at his dad’s auto parts business in Newton, rides in his car to and from BC High, hockey games at the Wainie – belong only to us. And that is fine by me.

Tags: