July 30, 2020

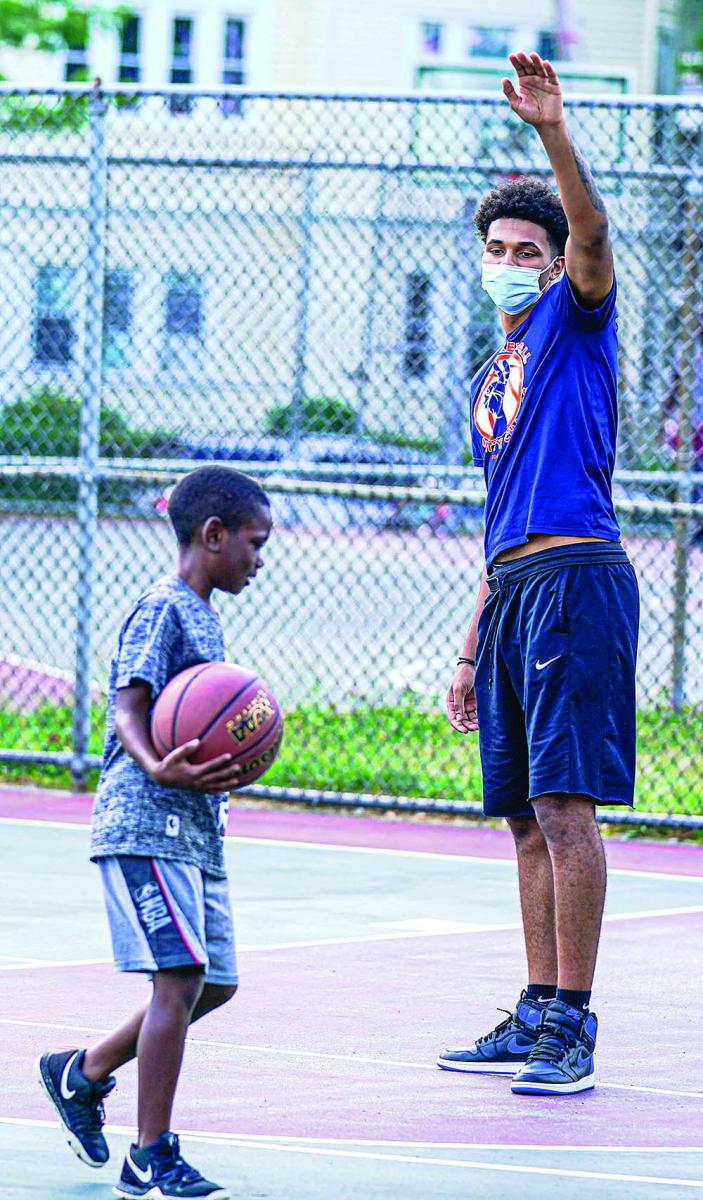

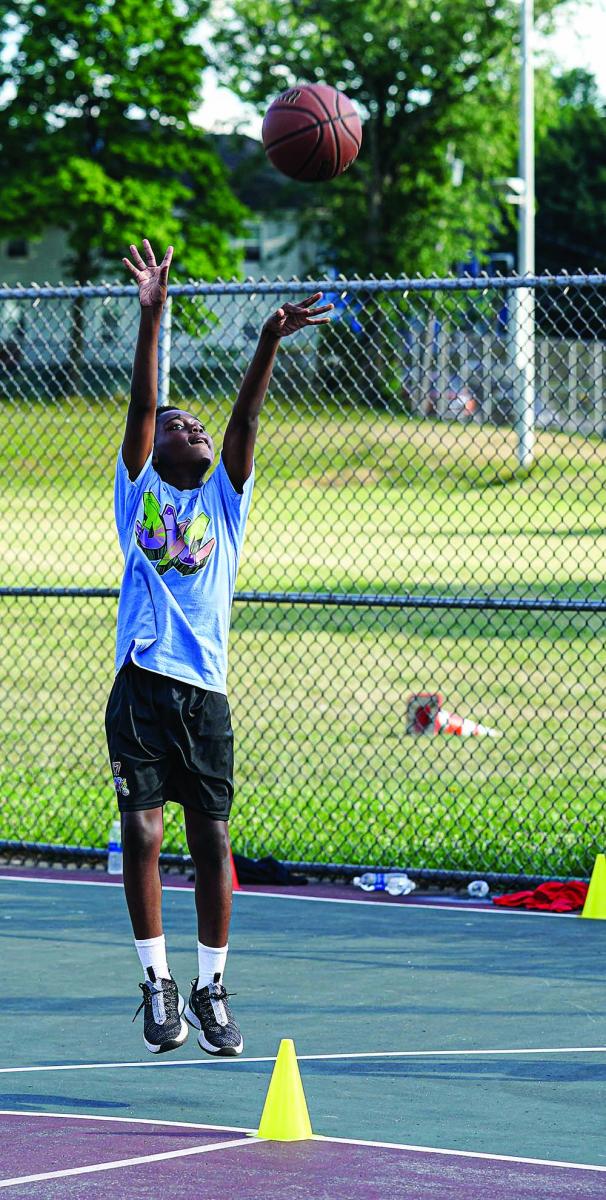

Distanced basketball drills resumed on the courts at Town Field in Fields Corner after Dorchester Youth Collaborative brought back its athletic programming earlier this month. Photos courtesy DYC

On Monday afternoon at Dorchester Youth Collaborative’s Fields Corner headquarters, Emmett Folgert and his small staff were spread across a cluster of sofas, engaged in solemn conversation. On the other side of the room, four teenagers wearing masks ribbed one another, eyes glued to a TV screen as they played a basketball video game.

After the mayor declared a heat emergency that morning, Folgert decided to move the day’s activities into the air-conditioned space instead of on the basketball courts baking in the sun just across the street at Town Field.

Since Folgert founded the Dorchester Youth Collaborative (DYC) in 1981, the non-profit organization has been a place of refuge for neighborhood kids and a source of mentorship meant to steer them away from drugs and gang violence and toward job opportunities and higher education. On Monday, it also provided shelter from the sweltering heat.

As the staff talked among themselves, a senior volunteer — whom the kids know only by his nickname, Nugget— posed a question: “Why are kids dying to die?”

The previous day, the older brother of a DYC teen member had been shot and killed on Sumner Street in Dorchester — the fourth gun homicide that week and the tenth in Boston in the month of July.

Folgert considered the question carefully, then answered: “Many of them feel they have nothing to lose. The ones who have given up. Nobody starts out wanting to be a gang member, nobody starts out wanting to be afraid that somebody’s going to shoot them...our part of it is prevention and diversion. If we can get kids from families that have relatives, brothers, or cousins who are gang members, we can keep them out of gangs.”

That’s the mission at the Collaborative, a mission made even more difficult by a pandemic that closed the center for weeks, leaving teens who typically head to their Fields Corner space with no place to turn.

(l-r) DYC kids Joshua, Garvey, Lawrence, and Diamani beat the heat on Monday with a game of 2K inside the organization’s Dorchester Ave space. Daniel Sheehan photo

Safe City Academy, the organization’s workforce development program for kids 15-22, was back up and running three weeks after the shutdown began in March with a pivot to a food distribution program in which older DYC workers delivered 14,000 pounds of food to Catholic Charities food pantries throughout the metro area using a rented tractor trailer truck.

“It was really an opportunity for them to be heroic,” said Folgert. “People were depending on these young people.”

But for the younger kids in the program, there weren’t many options. The center went remote, checking in with kids virtually, helping them keep up with any online classwork, and purchasing gaming systems and sports video games for many of the kids. “We spent years getting them off video games and then immediately put them back on them,” Folgert noted with a chuckle. The effort to keep kids engaged and inside was expensive, but largely successful.

Since July 13, a group of 25 younger kids and 7 staff members has resumed their basketball and track programs at Town Field. Still, life in limbo during the pandemic, especially during the early summer months, was troubling, said Folgert.

“Everything we use to prevent young people from getting involved in that disappeared. What do we use to keep people from getting into violent lifestyles and joining gangs? The centers — they were all closed. Jobs? They were all shuttered,” he said. “All of our tools were gone, yet the violence was continuing. Now we’re starting to load those diversion programs back in. But it definitely was a terrifying period to have violence continue and not have the tools that work to prevent it.”

The kids in the organization are no strangers to that violence; the deeply personal link to Sunday’s shooting fatality proves as much. But many of them have come to appreciate DYC as a second family.

“Emmett’s like a dad to me,” said Garvey, a 7th grader at the McCormack School. “He helps my family. Like on Thanksgiving he brought food for every family. He’s taken us to college football and baseball games.”

Diamani, 14, described the mentors at DYC as “people who I trust, who I can talk to about most stuff. They make me feel welcome here.” He explained how he was involved in a “cyph” —a small gang-like cell— before Emmett “convinced me to stop doing all that stuff, to do my own thing, and worry about myself. And there’s like no kids really in cyphs now. Emmett and his staff here are the reason for that.”

Lawrence, another 14-year-old, said spending his time at DYC has helped him develop as a person. “Personality wise, I used to be very hyper. It’s helped me calm down, so like, I know when to play and when not to.”

In recent weeks, Lawrence, a budding cross country runner, said he’s enjoyed taking on the role of basketball and track coach and working with younger kids in the program. Even at a relatively young age, he’s already setting examples for his peers.

“I’ve never been in a gang personally,” he said, “but I used to hang around a lot of people who were in gangs. A couple of my friends were getting jumped and getting into different stuff, and I told them if you hang with me, come to DYC, it could change your life.”

Lawrence’s life now, he said, is decisively better. “Before I started coming here, I would never leave the house. I’d just go to school and then come home and play video games. But now I come here after basketball practice, do homework, get some pizza or something, and hang out here until around 8:30.”

COVID-19 has strained the organization’s resources, which have been dwindling in recent years. Because of a need to hire more staff and acquire ample PPE, the pandemic “makes everything more expensive,” said Folgert.

An injection of support could help the organization acquire priceless assets: a new van to safely drop kids off at their front doors; an expansion of the workforce development program at the Kenny School. Closer collaboration with other agencies could help, too.

Folgert pointed to a recent RICO drug trafficking bust in the Bowdoin/Geneva area that took 20 gang members off the streets as another opportunity to make inroads.

“We don’t know when these busts are going to happen, but once they happen, that’s a golden opportunity to have a bunch of us prevention and diversion people at the ready to go into those neighborhoods and flood them with positive alternatives.”

A new round of funding from Boston After School and Beyond that will send $500,000 in grants to 34 local programs will make a small dent in DYC’s obligations. But other sources of funding that kept the organization afloat in the ‘90s and ‘00s have dried up.

“We don’t get any [federal money] right now. Our funding streams are mostly charitable donations...We really could use more donations. It’s a time that people can step up and support these kids.”

Joshua, 11, hoisted a shot while sporting an official DYC t-shirt. Photo courtesy DYC

For now, seeing smiles on the basketball court is a small victory for kids who saw their sports seasons and summer camps cancelled and their lives upturned.

“I’ve been doing this for over 30 years, and I’ve never seen a generation lose so much,” said Folgert. “It’s a really significant loss that these kids are experiencing, and to be able to put some programs back up is just thrilling, and they really appreciate it.”

With the uncertainty of school re-openings looming in the near future, however, the challenge of keeping kids safe will persist. Folgert knows that the stakes of the pandemic, like the stakes of his lifelong work, are those of life and death.

“They’re never going to forget how we treated them during this pandemic for the rest of their lives. They’re never going to forget it, one way or the other.”