May 6, 2020

Relatives of Cynthia and Clasford Johnson, who were interred at Cedar Grove Cemetery last weekend, are shown by their grave. Only ten members of the family were allowed to be present at the burial. Photos courtesy Amos Monteiro

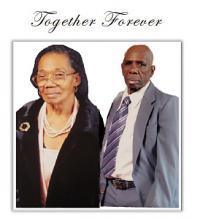

She was the matriarch and died first; he didn’t wait that long to join her

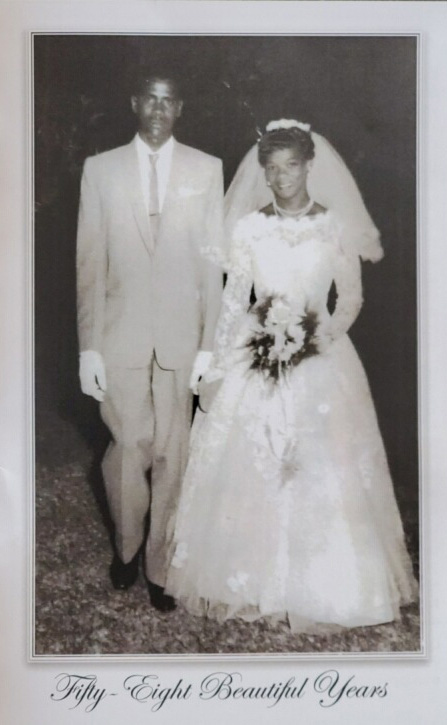

Cynthia Johnson and her husband Clasford were married for nearly six decades. On Saturday, they were buried together in a joint funeral at Cedar Grove Cemetery in Dorchester, their adopted home since the 1970s.

The Jamaican-born couple, who were residents in the same Hyde Park nursing home in recent months, died just five days apart.

Mrs. Johnson, 85, passed away from “natural causes” on Friday, April 24. It is not known for certain if there were any complications related to COVID-19.

Mr. Johnson, 84, died on April 29. He had tested positive for COVID-19 three weeks before, but never developed severe symptoms from the illness. He was, according to family accounts, not killed by the virus.”

Two of his grandchildren, Amos Monteiro and Tintra Monteiro, said that they believe that Clasford Johnson’s rapid decline in health was due to the loss of his beloved “Cynti.”

His death was not expected, said Tintra, who works as a nurse in the Intensive Care Unit at Boston Medical Center where she has watched the virus ravage people far younger than her grandfather.

“He was never in great health. He was diagnosed with COVID-19 about 17 days before. But he had been doing very well. He didn’t have all of the classic symptoms. He was a very strong, physical man,” she said.

The husband and wife lived in different rooms at the nursing facility in Hyde Park. As Cynthia’s condition worsened— and it became clear that death was near— her family arranged a final visit for the couple.

“Two days before she passed, we decided he should be brought in to see her,” said Amos. “He was wheeled in and he sat on her bedside and they both kind of fell asleep together.”

Clasford began to fail in the hours after his wife passed away. Even though he suffered from dementia— and frequently forgot the names of friends and family— he never stopped asking about his Cynti.

“I believe that he knew that she had passed and he took a rapid decline,” said Amos, a Boston firefighter who lives in Dorchester.

His sister agrees. “I’m in the medical field and we deal in science,” said Tintra. “But the minute she went, he knew this is it. She was his lifeline; that’s the only reason he was still there.”

Cynthia Valentia Rose was the youngest of three children born to Iris Miller and Stanford Rose in Craighead Manchester, Jamaica, in 1935.

Later, her mother married Barry Green and settled in Kingston. That is where she met her future husband, Clasford, who hailed from a different part of Jamaica, the second eldest of Estelle and Ivan Johnson’s 14 children. Cynthia and Clasford— who was also known as “Vernon”— were wed in 1962 and welcomed five children: Janet, Howard, Andora, Robert, and Denniston.

In 1970, Cynthia was granted a visa and moved to Boston, where she worked as a seamstress at the Jewish Memorial Hospital and Rehab Center. Her husband and her four youngest children joined her in 1971 and 1972, by which time she had already found the family a home on Tonawanda Street near Fields Corner, which they acquired in 1973. (Their eldest daughter Janet emigrated to London, England, in 1970.)

“Our entire family sort of revolved around the house on Tonawanda for a very long time,” said Amos, who grew up spending nearly every weekend with his grandparents while his mother, Andora, worked. “There were several other West Indian families on the same block.”

“My grandmother’s house was kind of like an international airport,” he said with a laugh. “People would come from all over and stay for a few days and sometimes a few weeks at Tonawanda. We’ve had a lot of contact with our family abroad and that’s because of Cynthia. She always kept in contact. Every year, several times a year, they’d come and stay. Her home was really the epicenter.”

Cynthia was doing all of this while also caring for her husband, who suffered a stroke before the age of 50, a setback that limited his ability to work as a mechanic— his chosen profession.

She also remained devoted to her faith.

Rev. Bruce Wall, her pastor since the 1980s at Dorchester Temple (later Global Ministries Christian Church) on Washington Street, recalled that Cynthia was a critical influence in his early days in co-ministry at the Codman Square church.

“Cynthia was there before I became the pastor and I was there for 27 years. She brought me in and she was critical to my staying and surviving as a pastor,” Wall said.

Wall remembers Cynthia as “loveable, laughable, warm. There was a whole Caribbean community at what was then known as Dorchester Temple. And once Cynthia found out that my people were from Jamaica, I was ‘in like Flynn.’”

Rev. Wall was part of a two-man, interracial pastoral team alongside Rev. Craig McMullen, a white minister. It was experimental for the Baptist congregation.

“Cynthia saw the potential in Craig and me. She gave us encouragement and love and counsel through it,” said Wall, who officiated at the funeral last Saturday.

“When she stopped coming to church, we would go to her home. We gave her a radio and said, ‘You can be part of our church even if you cannot come.’”

If she couldn’t pray with her fellow congregants on Washington Street— or be present for their family milestones— there were other more personal pursuits.

“My grandmother would cook every weekend,” said Amos Monteiro. “She worked as a seamstress, but even when she was home, she would be on the sewing machine: pillows, dresses, curtains, whatever.”

“She spent a lot of time doing that,” said her granddaughter, Tintra. “She was a pint-sized little person, but she was so strong. Even later in her life, you could see the muscles in her legs.”

“The lottery was big,” said Amos, again laughing. “She loved numbers. I think she was a little superstitious. She would dream numbers.”

He added: “She held the family together. One of the poignant things is that my grandfather, he lived a rough life. He’s been kind-of-old my entire life. We joked that grandpa will outlive everybody; that’s always been the joking narrative."

“When our grandmother died and he passed a few days later, we knew the reason.”

There was no advance “plan” to bury the Johnsons as a couple on the same day. Cynthia was ill and her death was anticipated. The family had arranged plots and services through Dolan’s Funeral Home five years ago. When Cynthia died peacefully on a Friday afternoon, the plan just kicked in. But it soon became clear that Clasford was letting go— and the family hit “pause” on the next steps.

By last Wednesday, it was clear that he would be joining his bride in a final repose. Her funeral was delayed to allow for a joint service and burial.

“We had a viewing at Dolan’s,” said Tintra. “There could only be ten of us and we walked in in family pairs at different times to observe social distancing. We proceeded to the cemetery where we listened to Pastor Wall and had the final services.”

It’s tough enough to endure one loss. Two?

Pastor Wall said it was the first in his long pastoral calling. “I’m used to giving a sermon and eulogizing in a church. But in this case the actual service was at the gravesite. No chairs. It was so awkward. But you have to create an atmosphere of love and support. This is new for us, too. It’s a culture shock, but we have to provide that love and support in this whole new environment.”

For the family, the absence of a wake translated into a relentless series of phone calls. The extended Johnson clan elected to create a video record of the burial and related services.

“We made sure we got some pictures of us and the caskets and we recorded a video of Pastor Wall and the ceremony at the cemetery,” said Amos. “We’ve been ‘What’sApping’ people in Jamaica and England and Pennsylvania.”

It’s no coincidence to their grandchildren that Amos and Tintra Monteiro are on the frontlines of the pandemic that complicated— if not claimed— the lives of their grandparents.

“They remained together for such a long time,” said Amos. “We’ve all done well and are still doing well. I attribute it to Tonawanda Street, to my grandmother primarily; the work ethic and the manners.”

“She was the epicenter,” says Tintra, who is safe and managing the crisis she faces every day in the ICU with her grandmother in mind.

“She never missed work. If she worked every day, it didn’t matter. Her door was still open. She held the family together.”