October 29, 2020

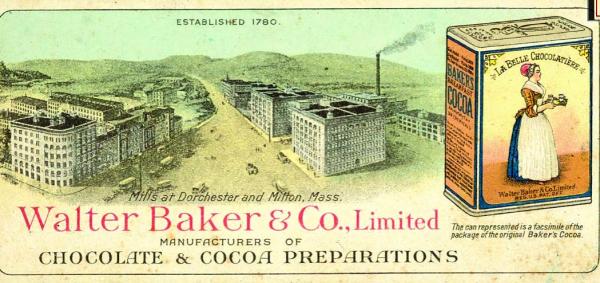

19th century advertisements for Baker’s Chocolate featured the company’s trademark “La Belle Chocolatiere” illustration and touted the purity of their cocoa, made “without metals or chemicals.”

In anticipation of an abnormal Halloween, staff from the BPL’s Leventhal Center for Maps and Education have organized a “virtual candy tour” that highlights several key elements of Boston’s storied candy-making history, including a handful of confectionary landmarks in Dorchester.

Rachel Mead, Public Engagement & Interpretation Coordinator at the center, spearheaded much of the research for the project. She explained that the idea of exploring Boston’s candy story came to her while she was geo-transforming maps for the Leventhal’s Atlascope tool.

“You can find some pretty cool stuff when you’re staring at these atlases all the time,” said Mead. “Something I noticed was all these candy factories and confectioners...Boston has this really deep candy manufacturing history, and it’s true of all of Greater Boston.”

Today, most of those manufacturers have moved out of state, including many from “Confectioner’s Row,” a stretch of factories in Cambridge that gave the world sweets like Necco Wafers and Junior Mints.

But the physical legacy of confectioners remains in Dorchester, largely in the form of the old Baker Chocolate Company complex in Lower Mills, the oldest producer of chocolate in the country.

Mead noted that from a cursory analysis of the antique Leventhal maps, the longevity of the Baker enterprise indicates its importance as a fixture in the community.

“There are not a lot of things on every map layer from the mid-19th century to the early-20th century, but Baker’s is one of them,” she said. “You can see it on the 1874 and the 1933 map— a span of almost a dozen atlases from that time period. So, it’s long-lived, and it was clearly important to the neighborhood around it.”

The business opened as Baker’s Chocolate in Boston in 1780, at a time when a population of sweet-toothed New Englanders and the city’s central role in the notorious triangular trade operation combined to create an environment ripe for chocolate-making, but not for history.

That trading prospered at the cost of countless lives. The region’s merchants shipped goods like New England-made rum to Africa in trade for slaves who were then shipped back across the Atlantic to plantations in the Caribbean and, later, the American South where raw sugar/molasses, and then cotton, mostly harvested by slaves, were purchased and brought back to New England to make rum and to supply the cotton mills with the goods to make clothing.

In those days, a lack of refrigeration made chocolate a tricky business experience, explained Mead.

“Before there was refrigeration, with New England summers, you couldn’t do the chocolate trade yearlong. So a lot of factories, including Baker’s, would stop manufacturing chocolate in the summer and temporarily become a paper mill or some other kind of mill.”

Maps of the time were created largely for fire insurance purposes and reveal little more than building material, zoning records, and property ownership. Nevertheless, the Baker lineage can be traced in the atlases alone, which show how the company was passed down through the generations for more than a century.

Henry Pierce, the step-nephew of Walter Baker, was the last “Baker” to own the operation after inheriting it following his uncle’s death in 1852. Pierce expanded the factory’s footprint in Lower Mills and engaged in an extensive marketing and public relations campaign to raise the chocolatier’s international profile.

Pierce went on to become a congressman and mayor of Boston. Upon his death in 1896, Boston renamed the intersection outside the Baker Chocolate Factory in Lower Mills “Pierce Square.”

Baker’s chocolate did have some competition in Dorchester, but most were in-house or small storefront operations that struggled to compete with the scale and resources of the large factory, said Mead.

While city directories reveal dozens of smaller manufacturers along Dorchester Ave. and other thoroughfares, she noted, “It’s hard to find the little stores, and the smaller stories that go along with them.”

However, the discourse around candy was well recorded in the local press. Using metals or chemicals for coloring was frowned upon, and attaining a certain purity or high quality of candy was prized, with Baker’s ads proudly touting their own purity: “No chemicals are used in any of Walter Baker & Co’s Chocolate and Cocoa preparations. These preparations have stood the test of public approval for more than one hundred years, and are the acknowledged standard of purity and excellence.”

Mead discovered one particularly testy exchange around an editorial that discouraged people from buying candy for their kids. An angry letter to the editor rebutted the author’s anti-candy stance: “Shall we next ban wheat, corn, and molasses?” they wrote.

While candy discourse has mellowed in the last hundred years or so, New Englanders are still eager to voice their strong opinions in a public forum. Mead said she had fun researching the topic, which remains a key aspect of the region’s history.

“I enjoyed digging up something really specific and very meaningful to the fabric of how these communities grew,” she said.