May 2, 2019

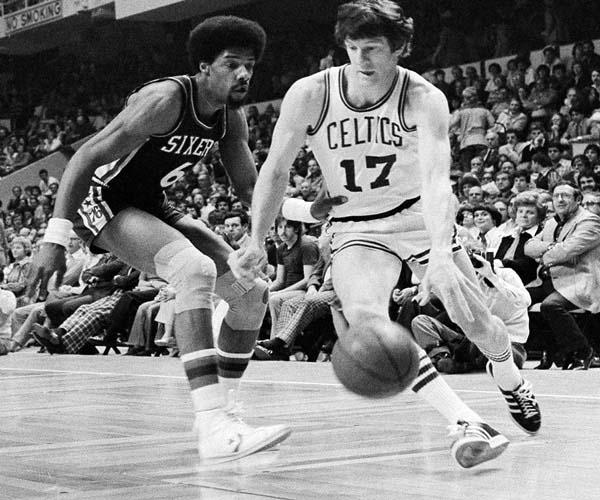

John Havlicek makes a move past the legendary Julius Erving during a 1977 game at the old Boston Garden. AP photo

John Havlicek, an eight-time champion with the Boston Celtics in his 16 years with the team, died last Thursday (April 25) at age 79. Former Boston Globe and Sports Illustrated columnist Leigh Montville, an author of bestsellers on Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, and Dale Earnhardt, covered Mr. Havlicek during his glory years in the 1960s and 1970s.

By Leigh Montville

I talked to John Havlicek’s mother once. She had come in from Bridgeport, Ohio, or wherever she then lived, for some playoff game in one of her son’s basketball years with the Boston Celtics. It was the only time I ever saw her in the Boston Garden.

I remember that she said the family owned a grocery store and lived on the second floor when John was young. I remember she said she was amazed at how he was always running everywhere as a kid, running, running, always involved in games of some kind, always running. I remember she said when he stopped running for a break, he would come into the store, go to the big commercial refrigerator, take out a quarter-pound stick of butter, and eat it like a popsicle. He would do this all the time.

“A stick of butter?” I asked in a tone of disbelief. “A stick of butter,” she replied in the same tone.

From that moment, I always thought—back of my mind—that maybe this was his secret. He had some extra lubrication, some kind of Pennzoil of the body, or something that made the parts work just a little bit better than everyone else’s parts. How else to explain what he did? He could keep going and going and going. He never had to stop.

For 16 seasons (1962-1978) in a game played by the best athletes in any professional sport, he could wear down anyone and everyone. There might have been players who could jump better and shoot better and dribble better—though not a lot of them—but there was no one who had his endurance.

He was 6-foot-5, 203 pounds, a perfect basketball size. Tall enough to play forward. Fast enough to play guard. To play against him on defense was a basketball nightmare. He would take his man on long and treacherous trips through forests of arms and legs and well-set picks, all at high speed. Oops, he was free for a jump shot. He would spring free on fast breaks. Oops, a lay-up. Oops, another lay-up. And another. He would slide inside for rebounds. He would edge off his man, counting in his head as Hal Greer of the Philadelphia 76ers had to throw the ball in-bounds within five seconds in the seventh game of the NBA Eastern finals on April 15, 1965 and … wait for it … steal the ball. Havlicek steals the ball. (Look it up.)

He played for eight Celtics teams that won NBA championships, filling different roles in each of them. For the first four, all in a row, he was a legendary sixth man off the bench on teams dominated by Bill Russell’s defense and offense from Bob Cousy and Tommy Heinsohn and Bill Sharman. The next two—everybody but Russell and Sam Jones gone—he was a starter and a scorer. For the last two, Russell and Sam gone, an entirely different roster with Dave Cowens at center, he was a veteran presence, a scorer, a star. He played so long he was part of two Celtics championship eras. He was named an All-Star in 13 of his seasons.

“I never thought I’d play this long,” he once said. “I thought maybe eight years. That seemed to be the limit when I broke in.”

He was as amazing to his teammates off the court as he was on the court. Great attention was paid to his fussiness, his profound sense of order. He would hang up all of his clothes in his locker, even his socks. Who hangs up socks? He would arrange all his toiletries by height. Who arranges toiletries by height?

He would take care of the bill at all team dinners. No, he wouldn’t pay the bill. He would go down the list, making sure each player would contribute for that extra glass of wine or that more expensive entrée. Who cuts up the check like that in modern-day sports?

“Well, back then, nobody was making the big money,” Mal Graham, a Celtic for two championship teams, says. “These were the cheapest guys you’d ever meet.”

Havlicek maintained his sense of order even in his post-game interviews. While other players sometimes would talk to the cameras and notebooks more than the people behind them, Havlicek studied his inquisitors. He knew who asked what questions. He read the stories the next day. He put faces and bylines together.

“So-and-So gets it wrong every time,” he said once. “I try to repeat everything for him, just to make sure he understands. I spell it out. And then he gets it wrong again.”

He was always a terrific interview subject. He took time, answered everything. (Even if he knew it might come out wrong the next day.) He liked to talk about college, Ohio State. Did we know that the Ohio State NCAA championship team of 1960 set a record that will never be broken? No, what was that? Every player on that team graduated from Ohio State. A couple had gotten masters degrees, a couple doctorates. Every one a graduate.

“I had to work at it at Ohio State,” Havlicek said. “Jerry Lucas (the All-America center) was my roommate. It would be finals week, and I’d be sitting there with all my notes, a line of No. 2 pencils all sharpened, all my books, doing an all-nighter. Jerry’d come in, turn on the radio and read for half an hour and go to bed. I’d be up all night. He’d get the A. I’d be fighting for that C.”

I covered his last game on April 9, 1978. He had just turned 38 years old. It was a classic Havlicek production, everything planned with that fine sense of order, right down to the recorded rock music that was played during warm-ups instead of the usual organ stylings of John Kiley. His speech was perfect. The celebration was perfect. He scored 29 points. He wore a tuxedo to and from the game. The suit (and black socks and underwear) was hung in his locker.

I stayed around while he got dressed, stayed while he stalled and stalled, really not wanting to leave. All the other players had left. The coaches. The equipment men. The reporters. Everybody had left. He balanced a box at the door, let me out, and turned off the lights.

Perfect.

RIP, sir. You were a pleasure to be around.

This essay was first published by TrueHoop.com.