May 31, 2019

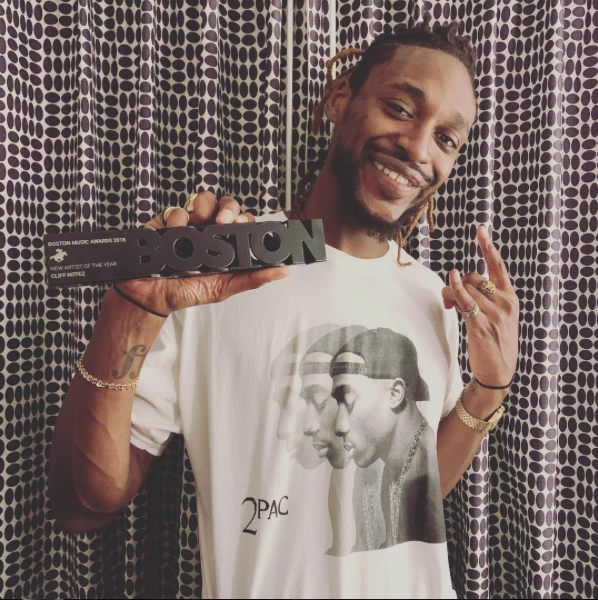

Cliff Notez, a rapper with Dorchester roots, won “New Artist of the Year” at last year’s Boston Music Awards.

Hip-hop is everywhere in Dorchester. Booming from the subwoofers of passing cars, and leaking from earbuds on Ashmont-bound trains. Irrepressible, it seems to seep up through cracks in the pavement, like splotches of oil under the baking sun. And from 7-10 p.m. on the last Tuesday night of each month, it rattles the walls at Dorchester Art Project’s nascent open mic in Fields Corner.

The monthly showcase is quickly becoming a proving ground for Dorchester’s wealth of artistic talent. A sign-up sheet for the event is posted at 6:30 p.m.; often, it’s full within minutes.

A frequent host of these open mic sessions, the multi-talented spoken word artist/promoter/talent manager Amanda Shea is one of the people driving Dorchester’s do-it-yourself (DIY) arts culture forward. A few years ago, as manager of the then-up-and-coming Anson Rap$, Shea vaulted over the barriers to access that historically have hindered black hip-hop artists in places like Dorchester and Mattapan. Most of the options for booking shows were rock and roll-heavy venues in Cambridge and Allston, where events would be a trek for fans in the southern parts of the city. And those venues weren’t always friendly places.

“That’s when I started realizing that there was a lot of pay-to-play things happening,” said Shea. “There were a lot of places that didn’t foster hip-hop because of the negative connotations that came with that, whether it be fighting, violence, gunshots, drugs, alcohol, sex. All these very weird, negative things attached to hip-hop were keeping it out of the scene.” So, said Shea, “we were like, [eff] this, we’re gonna take a different approach.”

.

.

Amanda Shea hosting BAMSFest last year. Photo by @d_irvin

In November 2017, she decided to buy out Sonia, the new sister club to The Middle East, plan an event glibly titled “Surprise!”, and fill the bill with Dorchester and Roxbury-based talent. After a “thorough promotion process,” she managed to pack the club with fans – and get every artist paid.

The success of the event uncovered a new template for rising hip-hop artists to use to book shows, one rooted in the independent spirit of DIY house shows that has traditionally characterized the city’s hip-hop scene. In the years following, Shea has noticed a sea change. “I feel like we’re shifting,” she said. “We’re starting to finally come together and be like, we all care about art, how can we make a space for us?”

Anson Rap$ also senses the gravity of the moment. “I seriously think that if there’s ever gonna be like a documentary on Boston rap, last year was the pivotal moment of rap,” he said, noting how Cousin Stizz, Fields Corner’s most commercially successful export, rose to success and showed other artists from the area that “they could do it, too.”

Stizz left Boston to make it big in L.A., a formula that area artists have long considered to be necessary for success on a national scale. But as Anson and others noted, that narrative is gradually beginning to change.

“I think that psychology comes from just thinking, you know, all these other people from Boston left, so I got to leave. But I think people are starting to figure out that being from Boston is actually one of the best places you could be as a musician.”

Dorchester-based artist and self-proclaimed "art rapper" Anson Rap$.

Cliff Notez is another figure in the forefront of making space for black artists in Boston. The rapper and filmmaker split his adolescence between Dorchester and Somerville, an upbringing that nurtured in him an acute awareness of how different life can be at opposite ends of the Red Line. With that cityview in mind, he founded Hipstory, a multimedia organization with a mission of “creating a platform for marginalized stories and identities to be told and heard.”

Last Saturday, he headlined Boston Answering, a show at the Strand Theatre that Hipstory organized along with community arts advocates DAP and Hood Aesthetic as a response to a Boston Calling festival that this year largely shunned Boston-based talent in favor of more national (and whiter) acts.

Notez sees the Strand as Boston’s equivalent to Harlem’s Apollo Theater, and with good reason: New Edition got their break at a Hollywood Talent Night at the Uphams Corner spot in 1981. As such, he reasoned, the lineup and the venue are “more true to what Boston really is.” Furthermore, he explained, the festival was a celebration of the collective movement that is building a concrete foundation for hip-hop in the city.

Cliff Notez performing at Boston Answering, a festival organized by his non profit Hipstory. Photo by @serenasawthat.

“We’re all talking to each other, we’re all pushing each other up, supporting each other’s art,” he said. It’s something that has the backbone for the type of longevity that isn’t seen that often in the music world these days. It’s a special thing and we’re lucky for that.”

Sharing the bill with Notez on Saturday night was Red Shaydez, a Dorchester-based MC born with hip-hop in her blood; her father is a rapper, her mother a DJ. As a child with a “big imagination,” she developed a “mixtape” of tracks by ten different invented characters with unique voices and flows. Today, that theatrical sensibility remains in her act.

“I don’t perform without them on,” she said, referring to the famous red sunglasses behind her stage name. “When I put them on, I feel like another person. If you see me in places like this, like a coffee shop, I’m sweet, I’m pretty shy. But on stage, I’m like super gangsta.”

.

.

Red Shaydez took the stage at Boston Answering at the Strand Theatre on May 25. Photo by @serenasawthat

Shaydez’s lyricism is honest and often seeks to impart some wisdom to her listeners. On “Little Sabrina,” a track kindred to 2pac’s “Brenda’s Got a Baby,” she tries to mentor a troubled teenage girl with low self-esteem; in the song’s music video, she appears as a friendly samaritan at a Fields Corner bus stop. On “Self-care ‘18,” she exhorts her overworked peers to take a day for themselves and relax in the tub with a glass of wine.

“That song is for everybody who works their ass off and forgets about themselves,” she explained.

Shaydez believes that after years of trying to break through a “glass ceiling,” hip-hop is finally being recognized as a Boston product. “Contrary to popular belief, hip-hop is popular here,” she said. “Yeah, we could be getting more support from the venues, but the fans are here, the support is there from the people.”

She often collaborates with Brandie Blaze, a fellow MC with whom she shares a “rap sisterhood.” Blaze, a born-and-raised OFDer, takes time in each of her songs to shout out her hometown. “I don’t have the thickest Boston accent, but I do have a bit of one and it comes out on the records,” she said with a laugh.

Blaze grew up idolizing rappers like Biggie and Lil’ Kim, as well as the Haitian-born rapper Dutch Rebelle, who made a name for herself after growing up in Dorchester. “That was the first time I saw a female rapper from here, so it was just like, Wow! I could do it, too,” she said.

.

.

OFDer Brandie Blaze reps Dorchester on every track. Photo courtesy Green Line Records.

For Blaze, last weekend’s show at the Strand was a source of immense pride. “A lot of artists here, we’ve been trying to tell people like, yo, there’s a scene here and it’s starting to get cohesion and starting to get attention...with [Boston Answering], they’re kind of kicking in the door. Something like that, you can’t deny it anymore.”

Her rap persona contrasts starkly with her everyday personality; on the mic, she’s loud, aggressive, and unapologetically confident. But in her mind, she’s simply emulating some of her favorite MCs.

“I like the idea of subverting gender roles in hip-hop,” she explained. “I’m a huge, huge hip hop fan, I even consider myself a scholar, but it’s misogynistic as hell! You don’t wanna keep hearing disrespectful things...so I try to push as far in the opposite direction as I can, just like embracing and owning my sexuality.”

Blaze recently teamed up with Red Shaydez to cover the Doja Cat song “Tia Tamera” in a nod to their sororal relationship. Collaborations like this, in which one Boston artist is featured on another’s work, are the norm in such a tight-knit music community. Most musicians here are willing to extend a hand to someone a few years younger, someone like 20-year-old Adonis Woods, one of the featured artists at last month’s DAP open mic.

.

Adonis Woods performing at last month's open mic at the Dorchester Art Project in Fields Corner.

Many of his songs deal with “being black and growing up in Boston,” a reality where violence and racism surround him on a regular basis; on one track, “Warchester,” he dodges literal and metaphorical bullets. “Straight from Dorchester/Please don’t let the war get ya,” he raps, a survival plea to his peers. Like other young MCs in the city, Woods uses grandiose terms like “infinity” to describe his aspirations. But at the end of the day, he also knows it’s mainly about doing what makes him happy.

“Boston’s small, but the world is big. I wanna travel, tell my story to people, make a connection...for me it just comes from having a story you want to tell.”

Daniel Sheehan is the Arts and Features Editor for the Dorchester Reporter.