May 30, 2019

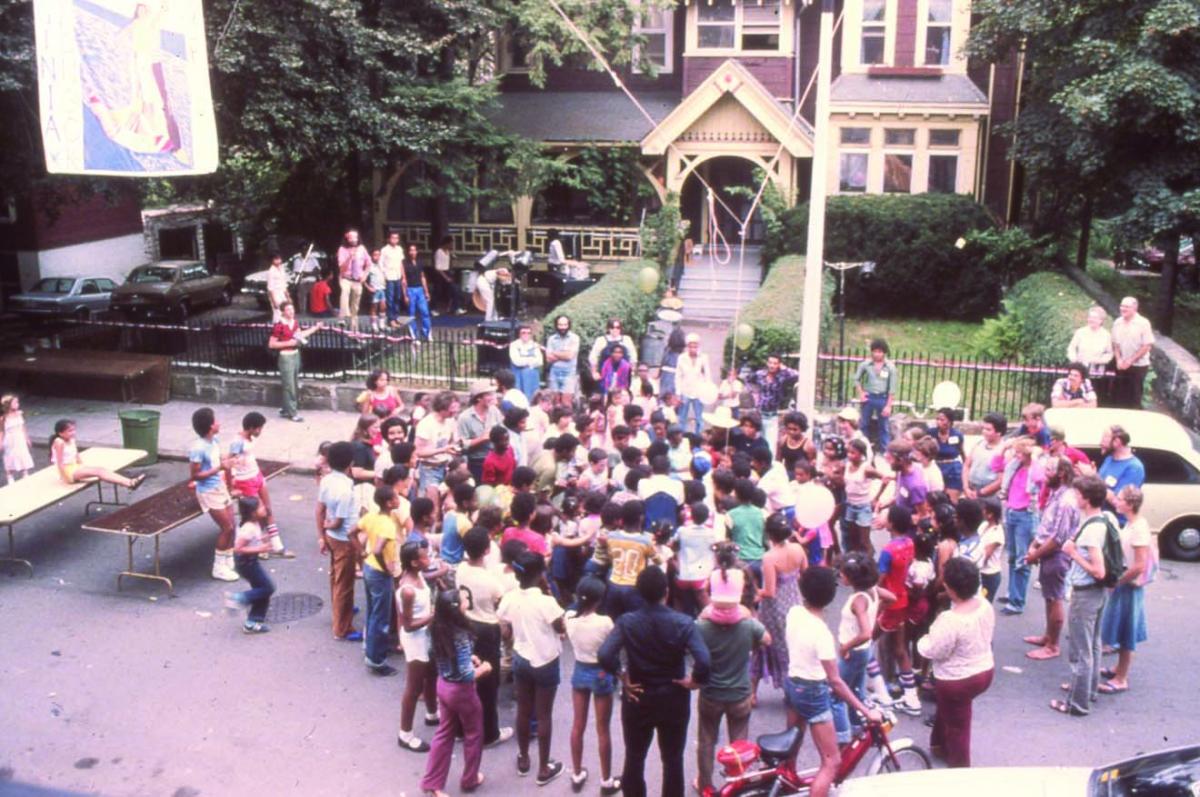

Young residents of Monadnock Street gathered before a 1979 block party organized by residents including Robert ‘Bob’ Haas, who recounts the efforts to build community and combat blight, crime and displacement in Uphams Corner in his memoir, ‘Monadnock.’ Park Daugherty photo

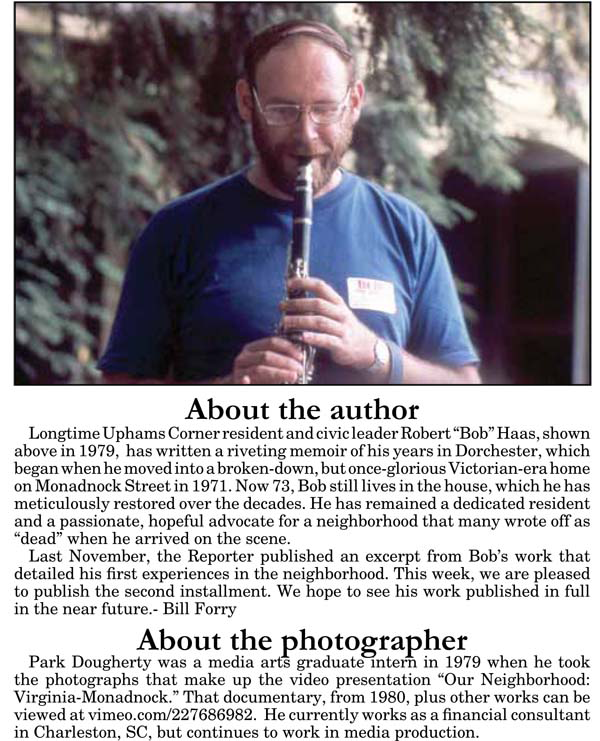

Editor's Note: Longtime Uphams Corner resident and civic leader Robert “Bob” Haas, shown above in 1979, has written a riveting memoir of his years in Dorchester, which began when he moved into a broken-down, but once-glorious Victorian-era home on Monadnock Street in 1971. Now 73, Bob still lives in the house, which he has meticulously restored over the decades. Last November, the Reporter published an excerpt from Bob’s work that detailed his first experiences in the neighborhood. This week, we are pleased to publish the second installment. We hope to see his work published in full in the near future.- Bill Forry

PART II Reclaiming the Street 1977 – 1987

It started off as Cemetery Corner. Set at the outskirts of the Puritan settlement of Boston, it was where the whole community buried its deceased. A chronicle of its history, the headstones told the stories of love lost, spouses who died too young, perhaps in childbirth, and children who never made it to adulthood. They also identified soldiers who had died in battle, except for the 40 from the Revolutionary War, who were buried in a common grave and remain unknown. And some marked the lives and deaths of slaves.

In those days, the 1600s, it was the exception if someone’s child survived long enough to marry and carry on the family name. One of the lucky settlers that way was Richard Mather, born in 1596, and buried in 1669 at age 72. A minister himself, he had four sons, also ministers, and one of them, Increase, became the first president of Harvard University. Richard lived to enjoy the prosperity of generations that followed him, including the childhood of his grandson Cotton, famous as a minister for his role in the infamous Salem Witch Trials.

The remains of two colonial governors who served over interim periods when the official designate was in travel are in the cemetery. One of them, William Stoughton, a bachelor with no descendants, also served as the chief justice of Massachusetts and as presiding justice of the special court that oversaw the Witch Trials. The other was Stoughton’s nephew, Richard Tailer.

Gravestones in the cemetery carried names like Capen, Clapp, Davenport, Bird, Humphrey, Holden, Baker, and Pierce, prominent families who started and led Dorchester’s famous Masonic fraternity, the Union Lodge. Their names live on in local street names, where later residents had no connection to the past history.

The big change at Cemetery Corner was in 1804, when Amos Upham opened a dry goods store there. Upham’s family had Puritan roots, but they were not of Dorchester. Amos moved there from a small town west of Boston. His store prospered so well that after several decades the crossroads became known as Upham’s Corner. This was where Dorchester’s only land route to Boston, through Roxbury, intersected with roads to other parts of the town. This was where Boston’s prosperity, built on trade with Europe and the West Indies, trickled into Dorchester. A second route to Boston, running north from the Corner, was opened in 1827 when a bridge was built across South Bay into the city. From then on, Upham’s Corner was a transportation hub.

Upham passed his store on to a son, James H, who became a prominent Mason and drew his father into the Union Lodge. Another newcomer to the area, William Sayward, joined the lodge shortly after James did, and the two of them served on a committee to honor the Centennial Year of American Independence and create a chronicle of Union Lodge from its founding in 1796 to 1877, the year it completed its work.

James was also a member of Dorchester’s last governing Board of Selectmen, and in that role he cast the deciding vote in 1869 to annex Dorchester to the City of Boston. Soon after that, Sayward sought property for subdivisions. The farmland that rose up the hill behind Upham’s store was where he created Virginia and Monadnock Streets. His naming of Virginia Street was inspired by a framed account he’d received of a meeting at the Masonic lodge in Virginia City, Nevada, which sat on the top of a 7,800-foot mountain. That group called itself “The Masons on the Mountain.” And, presumably for symmetry, Sayward named his other street Monadnock for the famous New England mountain.

With the influx of newcomers on subdivisions like Sayward’s and in local stores, the families of the Cemetery and the Union Lodge receded from view. A five-foot concrete wall that was built in the early 20th century made the gravestones all but invisible. The imposing brick building the Upham family added in 1895 to the top of their store became known as the Masonic Apartments and served from then on as meeting space for the Union Lodge, where descendants of the prominent families met up until 1950. That was when the Union Lodge departed for the suburbs, and its members, no longer local property owners, were mostly forgotten.

Around that time, the trolley tracks were being torn up, and a new Roman Catholic parish in the neighborhood , St. Kevin’s, was moving into prominence and looking for a site for its church. What might have been a dramatic arrival for Catholicism in the neighborhood was deflected when the empty Baker Memorial Methodist Church was demolished. An imposing stone edifice with a giant clock tower, it lasted only from 1891 to 1943, when the property was put up for auction. But the will of Mrs. Sarah Baker, who had left a substantial bequest to help build the church, stipulated that the property could not fall into the hands of the Catholic Church. Instead, the parish’s new worship space was retrofitted into a nondescript empty telephone exchange building, two blocks away from the Masonic Apartments.

The influx of parishioners into the St. Kevin’s congregation changed the neighborhood significantly. Irish Catholics were forbidden by church laws to join the Masons, but they had their own organizations within the parish. And they had had a school, next to the church, built into what had been an auto garage. A second floor was added there for classrooms, while the church hall took over the cavernous repair space, where previous owners could fix ten cars at a time, elevating them, if necessary, on lifts. The echo-challenged hall became the place for weekly bingo nights and yearly bazaars. And the front door was still wide enough to drive a car inside, in case the parish featured one in a raffle. Across the street, the Strand Theatre, where the parishioners first worshipped, was where the pastor’s annual Lenten passion play became a yearly tradition. “The Christus” drew audiences from all over metropolitan Boston.

For all that, by the time of America’s Bicentennial in 1976, Upham’s Corner had little to celebrate. Fires were tearing the neighborhood apart, the Irish Catholics were in full flight to the suburbs, and the Strand was closed. St. Kevin’s church still filled up on Sundays, but with worshippers from a potpourri of backgrounds and ethnicities, and the school, also multi-ethnic, was accepting students from outside the neighborhood. Twice every day, parents formed a parade of cars, dropping their young ones off in the morning and picking them up in the afternoon.

The neighborhood’s history was displayed in empty edifices; in the Masonic Hall; in the James Blake House (1661) down Columbia Road in the middle of what was once the Dorchester Town Common; and around the Cemetery, which was flanked by old Protestant churches with depleted memberships. The Stoughton Street Baptist Church (1870), was a white wooden structure with four slender spires on its bell tower, and St. Mary’s Episcopal Church (1888) was the work of architect Henry Vaughan, whose only other church design was the National Cathedral in Washington.

And history lay dormant inside the neighborhood’s homes, wherever their design details hadn’t been destroyed. Boston’s mayor by then was Kevin White, an Irish Catholic who was beginning his third term in office. His administration installed high intensity sodium vapor lighting on the main streets of Upham’s Corner, proclaiming it to be “The Great Light Way,” and promising that the new look would reduce crime. The city also renovated and reopened the Strand, which was where, in 1980, following his election to a fourth term, White broke tradition by moving the mayoral inauguration ceremony, for the first time ever, away from the esteemed colonial-era Faneuil Hall.

A Sense of Belonging

My perch at the top of the extension ladder was a great place to appreciate decorative details up close, on my gables, dormers, and roof. And I could admire the wider landscape of other roofs, angular peaks designed by the neighborhood’s architects a century before my arrival, visible in their full majesty only to the few who might climb up a ladder. Some of the roofs, not mine, still had slate. It was also a great place to watch the street.

On a crisp fall afternoon, a few months before the blizzard of 1978 caused its havoc, I was painting above and noticed a group of white people, five of them, walking up the street. I could tell from the way they moved that they were unfamiliar with the neighborhood. Otherwise, they would likely have kept their gazes focused on some infinite point and would have marched forward, taking care not to observe anything close to them. But these folks were looking around, staring at everything. They carried clipboards. One of them, a young woman, called up to me. She asked if I would come down and answer some questions, and I agreed to do so.

The five were graduate students in urban planning from Boston University, with a primary interest in historic preservation. I gave them a full tour inside as part of the interview, after which they described my house as a gem. They characterized Monadnock and Virginia streets, the focus of their study, as a “forgotten” neighborhood.

I was pleased by the attention my house and the street were getting, and by the fact that these students saw value where so many of my neighbors didn’t. But I was also skeptical. What difference did it make if some students said my house had what they called historic preservation value, if all they did was go off and write a paper about it? I vented, in words tinged with anger. I predicted that the street and its houses were headed toward their doom, with owners seeing no point in fixing up. I said, “If you want to save these houses, if you really care about this neighborhood, then tell the people who live here what to do to save ourselves. Otherwise, everything’s going to burn down and we’re all

The students fell silent. But, months later, after their report had been finished, they invited the people they’d interviewed to a final presentation.

That night, they described our houses as “forgotten mansions,” and they directed me to the appendix of detailed recommendations at the end of their report. Their Virginia-Monadnock Area Conservation Plan had as its goal to increase neighborhood confidence and commitment. Specific suggestions were outlined in six categories: (1) Sense of Community; (2) Neighborhood Security and Safety; (3) Housing; (4) Transportation Services and Facilities; (5) Community Services and Facilities; and (6) the Visual Environment. Present that night also were people from city government and they affirmed the recommendations. The final two pages of the report offered a Strategy Timetable and Budget, essentially prediction as to how long it would take to accomplish the objectives of their six categories, and what the effort would cost. And they identified funding sources.

A scene from “Our Neighborhood Virginia-Monadnock” slideshow created by Park Daugherty in 1980.

I had never been exposed to urban planning studies like this one. I’d never interacted with public officials or programs that expended public money. To me, recommendations on paper were nothing more than that. They weren’t good enough for me, and I said so. I asked how ordinary, unsophisticated people could act on the complicated list the students had presented. What should we, the residents, do first?

Most urgent, the students said, was to “create a sense of belonging in the neighborhood.” I didn’t see how that was possible, with the neighborhood drowning in negativity. I insisted that nobody felt like belonging. The students’ recommended first step was to form a neighborhood association. I bristled and argued that the recommendations were beyond the capacity of the neighborhood. And they seemed like more than I could do. I said I didn’t even know what a neighborhood association was. How could I form one?

Susan Harr, a planner from the Boston Redevelopment Authority, responded. She introduced me to some neighbors at the meeting, people I didn’t know, and suggested they might get involved. Next she introduced me to Joe Finnigan, the Director of the Kevin White administration’s Upham’s Corner Little City Hall. Joe was a young man who had grown up in Upham’s Corner and cared very deeply about the neighborhood and its future. Susan assured me that Joe would help me, and it seemed like he might.

After the meeting, Brandon Wilson, the leader of the student group, gave me more advice, and reading material. She provided me with a US Government pamphlet entitled “Understanding Your Community.” The pamphlet advocated first coming to an awareness of all the strengths in a particular geographical area and then giving it cohesion as a community, engaging the residents in celebrating the positive as much as possible.

Later that night, at home, I recounted the details of the meeting to my housemate Art, who was already engaged with agencies in the neighborhood. I told him about all the exchanges I’d had, about how abrasive I’d been. He skimmed through the students’ paper, endorsed their recommendations, and he told me he trusted Joe Finnigan. He urged me to trust Joe, too, and work with him. I had nothing to lose if I tried it, so I began a relationship with Joe, a man ten years younger than I, accepting him as my mentor. Joe wanted to convene a meeting as soon as possible, to listen to what the residents might say about the neighborhood.

We held that meeting in January 1978, during a much smaller snowstorm than the following month’s blizzard, and 30 neighbors came out. They were exploding with anger, fed up with housebreaks. No one that night, whether white, black, Hispanic, or Cape Verdean, had missed having their whole house turned upside down, having doors and windows smashed and drawers dumped on the floor.

A major presence that night was the Cape Verdean DePina family, and they came with a translator, Christian Pina. He was more than a translator. He was the leader among them, the spokesperson for the family and other Cape Verdean neighbors. None of the rest of them spoke directly to the group, but through Chris they shared that they’d had their eye on a family, two doors away from my house, who repaired cars in their yard and had a sign that identified their business as “Hermanos Unidos.” The Cape Verdeans suspected them of housebreaks, and had named them “Ali Baba and the 40 thieves.” Chris expressed the hope of the DePinas that the neighborhood ought to drive them out.

The Hermanos Unidos family didn’t appear at our meeting. If they had, we could never have talked about them. But with the freedom we had, the DePinas could be honest while Joe and other city officials could participate in the discussion and give us frank advice. They outlined methods they knew to drive the family under suspicion out of the neighborhood. And in less than a month, when the Blizzard of 1978 hit, it happened. When the temperatures suddenly dropped, their unheated house became unbearably cold, which forced the family to seek warmer quarters. And once they were gone the police, who by then knew they were squatters, raided the house and had it condemned.

Art, who’d developed community organizing skills as part of his social work studies, gave us advice at that first meeting on how we should form our neighborhood association. He recommended that we set up a steering committee to organize meeting agendas. It would be composed of stakeholders from all the ethnic and cultural groups in the neighborhood. We chose the members for the committee: Aida Pomales and her sister Ana Hernandez, originally from Puerto Rico; Juan Evereteze and Mordecai Wilson, African Americans; and Chris Pina to represent Cape Verdeans. I was to be the white representative.

The committee members were all recent comers to the neighborhood. And we discovered that each of us had good analytical skills. Each time we met, we dissected what we knew of the neighborhood’s malaise and tried to understand its trends. We strategized on how we could get people, especially homeowners, to stay in the neighborhood, and how we could create the “sense of belonging” that the students recommended. Our plan was for a multi-ethnic, multicultural sense of belonging. We would espouse equality among all the groups that made up the neighborhood. We envisioned a block party, to be held the following summer, as the time when we would express our new vision, when people would be outside and we could speak to all of them. We hoped that way to engage more people in stopping the housebreakers. And we had capacity to communicate in all the neighborhood’s languages, to translate at meetings and distribute Spanish and Portuguese flyers.

We convened the wider neighborhood in March, and again in April, having skipped a month for the blizzard. At the April meeting the neighbors named their new organization the Virginia-Monadnock Neighborhood Association and as soon as they did, they elected me the president. I was taken by surprise, stunned by such sudden trust coming from people with a multiplicity of ethnic backgrounds and languages. They hardly knew me. In just a few months, I’d gone through a transformation, from being an anonymous, discouraged homeowner who kept my distance to becoming the neighborhood’s abrasive complainer, and now I was the leader of an initiative to redeem the area. I had no idea how to proceed, but Art and Joe pushed me.

They set me on course each month when I convened the meetings, and they supplied ideas when I didn’t think I had anything to say. The new organization affirmed the steering committee’s date for our strategy centerpiece, the block party. It was to be late in August. Chris Pina and the Cape Verdeans assured me I’d have their full support. I hoped the party would be another round of DePina celebrations like the ones I’d witnessed when they shoveled out after the blizzard.

Sadly, evicting the Hermanos Unidos family from the squatter house didn’t take them off Monadnock Street. After the blizzard they continued living in another house, and that was one they owned. There, at least, they didn’t have a yard, and they couldn’t fix cars on the street. Joe had found the real owners of the squatter property who had affirmed for him that anyone using their yard would be trespassing and should be arrested. We were disappointed that our victory was only partial, but Joe had more ideas. If he could take the family’s house for taxes owed, they’d be off the street for good.

To reduce housebreaks, we also needed to seal off entry to our back yards through the railroad property, and for that we had an opportunity. The tracks were about to become a passenger rail link, taken over by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA). The scheduled rebuilding of Boston’s Southwest Corridor required temporary re-routing of all the trains that used the city’s South Station. Sixty trains every day, including all of Boston’s Amtrak linkages to New York and farther south, were to pass by on our tracks, right behind my house. It would be noisy. It would pollute our air with diesel fumes. And we had no choice about it. For the new service, the tracks would be rebuilt, and the upgrade called for eliminating a popular grade crossing. That point would be sealed off by a six-foot chain-link fence, which would continue behind all the yards on my side of Monadnock Street.

At our meetings in May and June, we argued with the MBTA, about how the fence would be installed and maintained, about the pedestrian overpass that was promised as a replacement for the closed street crossing, and about the trains themselves. Why couldn’t we, with so many trains passing through our neighborhood, get on the trains and ride downtown? On the train, the trip to South Station would be less than 10 minutes, compared to the bus and subway option then, which could take 40 minutes to an hour. The answer from some of the public officials, not Joe, was that our neighborhood was so bad, some person getting on the train in Upham’s Corner would likely assault the passengers. Concern for rider safety prevented stopping the trains. Also, even though there was already an Upham’s Corner station at Dudley Street, we were told that the cost to stop one train ran to thousands of dollars. We were in a weak position then, being a nascent neighborhood group, to argue with the MBTA, a state agency, and be heard.

I’d never been to a block party, and now, in the summer of 1978, I was going to run one. The best place for the party, everyone agreed, was right in front of my house. The police closed off the street. My front yard, the only one with enough space, was where the DJ set up. I ran long extension cords out of my house.

Joe Finnigan knew what to do. He got all the official permissions from the city, and he knew the DJ. I rented a helium tank and set it up on my front sidewalk, where my friend Kathy from church filled balloons and handed them out to the kids. Mordecai Wilson brought his grill around from Virginia Street and cooked hotdogs and hamburgers for everybody. Next, Joyceline Villaroel came down the street with a platter of food she’d prepared at home, West Indian rotí. And that was when Guta Alves, Elica Medina, and Elda Barros, the Cape Verdean sisters from across the street, came out, covered our food tables with plastic tablecloths, and set down giant pots of cachupa. Elda also brought out a paper bag filled with pastels, Cape Verdean pastries she’d made, stuffed with tuna. She passed her treats out on the sidewalk. Everyone had more than enough to eat.

Our plan for the block party was mainly to speak to the adults in the neighborhood, but it turned out to be mostly about kids. That was because most of the adults were parents, and for them to be attached to the street it had to be a safe place to raise a family. It was fortunate that I’d had the idea to have name tags. I asked each person to make one, with his or her name and address. Nearly everyone cooperated, largely because the kids promoted the tags, with great excitement. Older kids helped the littlest ones with their writing. The name tags helped me see exactly where people I’d been watching were living, and how many kids lived in each house. We used 300 name tags, and as many as 200 were worn by kids, all from the street.

Kids and teens gathered on Monadnock Street during a 1979 summer block party, which Robert Haas and other neighbors organized. Park Daugherty photo

The event culminated with dancing in the street. Neighbors, young and old, participated, representing all the cultures. A dance contest, emceed by the DJ, was the first time I noticed Lamar Johnson, from the apartment building at the corner of Dudley Street. Only 11 then, Lamar was a serious contestant for the prize. He lived part of the year with his father in New York, where he’d learned break dancing, new in 1978. The contest boiled down to two finalists, Lamar with his break dancing and an adult woman who excelled in a range of styles. The decision was tough. The prize was money collected from spectators, and the DJ wanted to award it to somebody. When he finally decided to declare a tie and divide the money, the mood turned ugly. Both contestants went away angry.

The block party succeeded for its purpose. People got to meet each other for the first time, and I got to discover which of my neighbors, some of them among the DePinas, could speak English. Chris Pina made a short speech urging people not to sell their houses, not to move away. And people we suspected of criminal activities listened to his comments about house breaks, acting just as engaged and supportive as everyone else. Afterwards, the steering committee renewed its commitment to our anti-crime agenda, which included that we’d repeat the block party the following year, without a dance contest. And the next year I had support, in my house, from a college intern who established rapport with the kids.

That fall the MBTA built its fence, and we, the neighbors, continued to complain, pointing out places where we were seeing people slipping underneath. We’d been promised that the fence would be embedded in concrete, two feet below the ground level, but it wasn’t. The chain link skirted the ground. The trains were scheduled to start running in October, and we continued to press, with other neighborhoods along the line, for the MBTA to provide us service. Finally, in November, just before they began using the tracks, the MBTA caved in and agreed to stop some of the trains, once per hour. We continued our fight with them, demanding fares equivalent to those in the subway, with a free transfer from the trains to the subway, and eventually we won some concessions, but not the free transfer.

In January 1979, a year after we’d begun our organization, I was encouraged to write letters to the city advocating allocation of federal block grant funds for two unfulfilled priorities: the setup of a Team Policing unit in our neighborhood; and a start on renovating abandoned houses. Neither of those ideas found their way into the city’s subsequent budget, but my proposals began fruitful conversations with the police department and with a nearby housing non-profit which I’d hoped would receive the renovation funds I’d requested.

In May of 1979, Rich Entel, a student from Dartmouth College, came to Boston to work as an intern in the neighborhood. He’d never lived in a major city before then. A school program at Dartmouth, under the William Jewett Tucker Foundation, connected him to Denison House, where his internship was covered by a stipend. He was to serve on the staff of the agency’s summer day camp, and my housemate Art, who had by then become the program director of Denison House, arranged for Rich to live in the house with us.

Each day, the Denison House day camp transported 40 lucky kids from the neighborhood to the agency’s facility in Rowley, Mass., 25 miles north of Boston. Rich joined the kids in the mornings and evenings on a school bus, and he swam with them in Camp Denison’s lake. He enjoyed those times, but he was bothered by how many more young people remained on neighborhood streets that summer, untouched by the Denison programs or any other planned activities. He could see, because he lived in the house with us, that a lot of those kids were on Monadnock Street.

After spending his days at the camp with the Denison House kids, Rich struck up relationships with Monadnock Street kids. He listened as they told him about the street and heard them light up with excitement about the street’s big event, the block party. Through the kids, he learned that the whole street was looking forward to repeating the good times they’d had the year before, and this time the block party could have the DePina family’s live band, playing for free. They called themselves “Tabanka Jazz,” they played Cape Verdean music, most of them were from the street, and they rehearsed in basements across from me.

Up to then, I’d not known that my neighbors had musical talent. Now, through Rich, I had a changed view of the street. He got as excited as the kids about the block party, and his excitement began to infect me. He made a major investment to work on the event, to plan a series of children’s games and activities for the afternoon. And he threw himself into making decorations, with kids helping him. They painted banners on bedsheets to hang on ropes across the street.

When they weren’t working on the block party, the kids invited Rich into their homes. Their families fed him meals of fish soup or cachupa. He got to hear stories from Cape Verde, about how the families traveled halfway across the world from Africa to their new home on Monadnock Street, about how excited they were to be living new lives in America. The DePina family accounted for more than half the young people Rich met on the street.

A young resident of Monadnock Street pays a visit to Bob Haas’ porch in 1979. Park Daugherty photo

Rich’s popularity brought a new ambiance to our house. Kids yelled across the street to him when he came out the front door. Kids rang the doorbell looking for him and hung out with him on the front porch watching him do sketches of the three-deckers across the street. They came to block party meetings on our front porch. They were also curious about me, and they asked a lot of questions, about who I was, where I came from, and how old I was.

Zaduca Alves, five years old at the time, believed it when I told him I was 250 years old, not perceiving or understanding that I was in my 30s. He and his older brothers, Antonio and Raoul, came over a lot, as did their sister Gina. Other times their cousins Chico and John Campos hung out on the porch. Chico and John also liked to put traps in my backyard bushes to catch birds. We let them do it. Kids who were not DePinas also came over to see Rich. They included Cape Verdeans Nanelou and Justin Fernandes, and Billy Vanes and Jimmy Villaroel, whose families were from Trinidad. Sometimes Miguel Melendez, whose family was Puerto Rican, would come up from the apartment house at the end of the street. He knew Rich from Denison House. The bond between everybody was attachment to Rich and excitement about the block party.

The second party was a triumph. We had 400 attending, and with our live music, most of them wound up dancing in the street. But once it was over, the anticipation was over and the summer was over. And Rich was going to leave. He couldn’t bear the anticlimax, the light dimming in children’s eyes. He tried, in the beginning of September, to create links for them to programs at Denison House. He brought some Monadnock Street kids into the headquarters in the Masonic Hall, hoping they’d mix with the Denison House regulars painting a new mural on one of the walls. His popularity attracted all the young people, at all hours of the day.

Kids became invested in the mural. They were invested in being with Rich and all the energy he brought to their activities. But it didn’t last. Finally, when he did leave, other realities at Denison House became visible. The temporary headquarters were not a good fit for the agency’s programs. The once-proud settlement house, unable to sustain its community work, was sliding away from the public’s consciousness, in danger of disappearing altogether. Neither Rich nor Denison House were players in the neighborhood’s subsequent transformation, but they left an imprint on the street’s culture, which has sustained through four decades.

Read the first part of 'Monadnock' here.