July 26, 2018

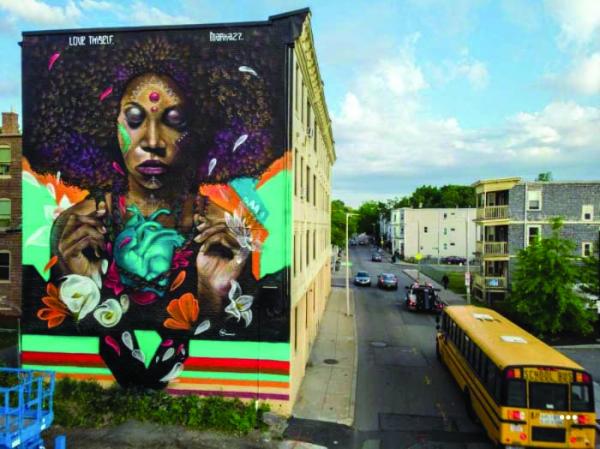

“Love Thyself,” by Victor “Marka27” Quiñonez. (Courtesy of the artist)

Just for fun, Jojo Vallera decided to take a different route through Grove Hall to visit her godson on Sunday. With him in tow, Vallera shuffled down Quincy Street until she let out a gasp and immediately scrambled for her iPhone.

“Wow,” she said, staring up at “Love Thyself,” the latest mural by Cambridge artist Victor “MARKA27” Quiñonez, who co-founded the artistic studio Street Theory. “All I can say is God bless the artist. It captures everything this generation needs to see. It captures the third eye, the heart and the soul, and it captures a black woman, with her natural hair, no less!”

Covering the entire side wall exterior of a three-story apartment building at 199 Quincy St., Quiñonez completed “Love Thyself,” at the end of May. It’s the last of five city of Boston-funded art projects along the Quincy Street Corridor and the Grove Hall Business District. In the last two years, the city has spent about $70,000 on the murals, art for utility boxes, and new banners throughout the neighborhood.

The mural centers on a black woman with a natural afro hairstyle, her eyes closed and her hands in a meditating pose, with bright, geometric patterns bordering her face and body. On her chest rests a luminous, turquoise heart, with lotus flowers and arum lilies intertwined around her arms and body. Quiñonez refers to his aesthetic as “neo-indigenous,” paying homage to Native, African, and Latinx ancestries.

“When I see her hair, I see my hair,” Vallera said, as she snapped photos. “So when I see this, I see myself.”

“The more you show the beauty of different cultures, the more you’re going to make people curious and want to know more about them,” said Quiñonez in a recent interview. “In Boston, if we paint a person of color on a wall, it’s always someone like Big Papi, and I want to change that.”

Quiñonez, who was born in the Mexican border city of Juárez, grew up in East Dallas — where his parents emigrated — in what he describes as “a rough neighborhood where drugs, gangs, police brutality and violence were commonplace.” He began to draw cartoons for friends at the age of 4 and became obsessed with graffiti street culture by the time he was a teenager in the early 1990s.

After graduating from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 2003, Quiñonez met his wife Liza. They launched Street Theory two years ago. Part creative studio, part gallery, Street Theory aims to promote more culturally diverse visual and public art in Boston and Massachusetts.

Quiñonez’s city-funded mural marks a shifting public attitude toward public art in Boston. Historically, Boston’s approach toward public art, particularly street art, has been conservative — to say the least.

Quiñonez recalls Boston police arresting Shepard Fairey, the established contemporary street artist, most known for his red and blue “Hope” posters used by former President Obama — for old tagging violations, while on his way to a solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 2009. Under a plea deal, Fairey was forced to publicly apologize, renounce tagging and pay $2,000 to a Back Bay neighborhood group. Quiñonez also remembers the uproar stemming from artist duo Os Gemeos’ mural in Dewey Square in 2013, with some locals comparing the art depicting a boy in pajamas to a “terrorist.”

Which is all to say, Bostonians didn’t seem to appreciate street art in the way people in Los Angeles and New York did.

In the last two years, Street Theory has been at the center of major art installations including the Underground Mural Project at Ink Block, which transformed more than 100,000 square feet of grey walls and empty space under Route 93 into a unique urban park.

Karin Goodfellow, the director of the Boston Art Commission, worked closely with Victor and Liza on both the Dorchester murals and the Underground Mural Project. “Working with Street Theory has been an incredible opportunity for the Boston Art Commission. In many ways, their work fulfills the city’s goals put forth in Boston Creates,” she wrote in a statement. “Deeply committed to elevating and diversifying public art in Boston, they’ve stepped in to play a transformative curatorial role.”

“Love Thyself” also marks a new effort to bring meaningful art to under- served areas in Boston. Grove Hall Main Streets Executive Director Ed Gaskin said the murals, which were announced last November, are the most recent example of a much-needed influx in public art dollars. Grove Hall worked with the Department of Neighborhood Development and the Boston Art Commission to secure funding and placement for the new art.

“The mural actually should have been up a while ago, but it was found to be a bit controversial at the first site,” Gaskin said of the Afrocentric artwork. “We just couldn’t find a place to put it.” According to Gaskin, two commercial property owners passed on the idea, one calling the image “too powerful.”

“For me it’s frustrating because this would never happen in a place like New York or Chicago,” he said. “There’s a long history of Chicano art in those places and people have been exposed to diversity of culture, but a place like Boston, there hasn’t been enough of that, especially on a massive scale,” said Quiñonez.

On a recent sunny day, Corneilus “Chef Biggie” Lawson took a quick break outside of the Commonwealth Kitchen on Quincy Street where he helps run the Jamaica Mi Hungry food truck. Lawson knows the area well, having grown up in Dorchester and Roxbury. He watched Quiñonez paint the mural in May.

Lawson said he’s grateful for the art peppering the neighborhood where his son goes to school. He’s also hungry for more. When I explained the delays in finishing “Love Thyself,” he was confused. “Too powerful? What were they scared of?” he asked. “My wife was the first one to comment on it, and she just thought it was amazing. It’s just a strong, black lady just being beautiful. It makes me happy.”

Quiñonez said his own identity informs his aesthetic. “I’m trying to fight the fear that certain people are trying to instill, that all immigrants are criminals or if you’re from Mexico you’re a thief or rapist,” he said. “It’s the oldest trick in the book, demonize the others so you can divide and conquer. When I paint, it’s to empower and inspire.”

Dana Forsythe is a reporter who works for WBUR 90.9 FM, Boston’s NPR News Station. The Reporter and WBUR have a partnership in which the news organizations share resources to collaborate on stories. This story first appeared online and on the radio for WBUR’s The Artery on July 10.

Topics: