November 21, 2018

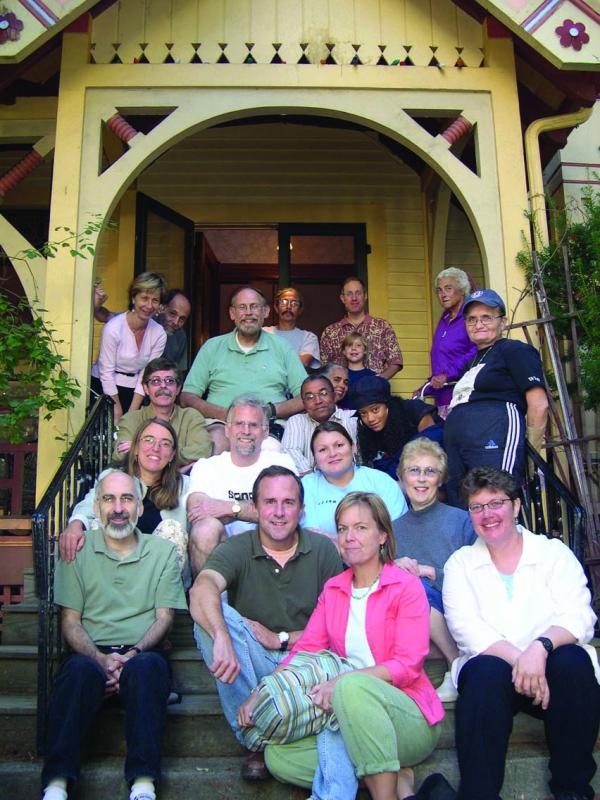

Robert (Bob) Haas – shown (top row, third from right) with friends and neighbors on the front stairs of his home on Monadnock Street, has written a detailed account of his Dorchester experience. Photo courtesy Bob Haas

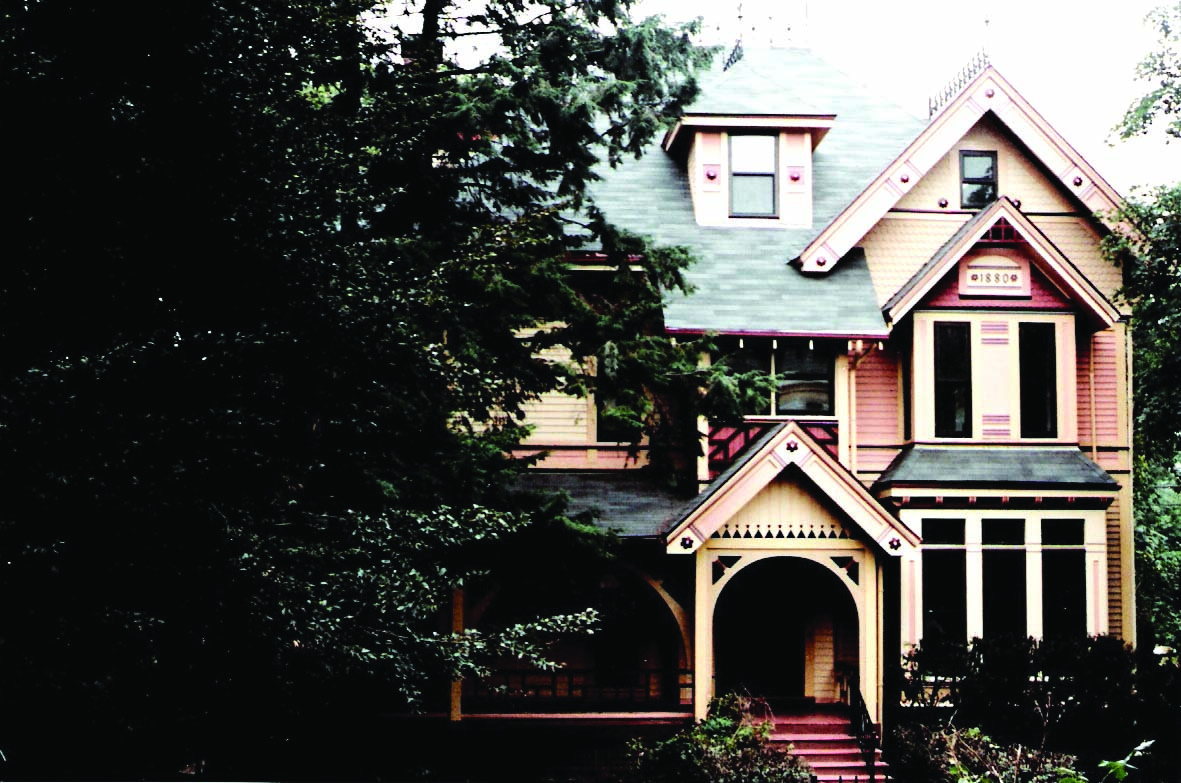

Longtime Uphams Corner resident and civic leader Robert (Bob) Haas has written a riveting memoir of his years in Dorchester, which began when he moved into a broken-down, but once- glorious Victorian-era home on Monadnock Street in 1971. Now 73, Bob still lives in the house, which he has meticulously restored over the decades. He has remained a dedicated resident and a passionate, hopeful advocate for a neighborhood that many wrote off as “dead” when he arrived in 1971.

This week, the Reporter is pleased to publish an excerpt from Bob’s work— which we hope will be published fully in book form in the near future.

FREE FALL: 1970-1979

When Boston annexed Dorchester in 1870, it set off a building boom. What had been a country retreat for well-to-do Bostonians, a scattering of farms where people spent their summers, turned into an urban grid, almost overnight. Two streets near Upham’s Corner were laid out in 1877 on a subdivision of rocky land obtained from the estate of a puritan settler, Ebenezer Sumner. At one end, Virginia and Monadnock Streets were joined together. They separated and ran roughly parallel to each other, downhill to the neighborhood’s commercial street, now known as Dudley Street.

Bends on Monadnock Street aligned it with the gentle curve of the adjacent Midlands Railroad. Trains stopped close by at Dudley Street and connected in minutes to downtown Boston. Prominent business leaders bought homes close to the station, in Monadnock Street’s row of new Victorian mansions. The grandest of them, a wood frame house with ornamental roof crestings, stood apart from the others at the middle of the block. It had wraparound porches and a long driveway that curved into the back yard, where the owners kept horses and carriages in a barn.

That house, number 29, was built for the son of George W. Smith, whose GW&F Smith Iron Company was a major supplier of Boston’s decorative cast iron. The company’s manhole covers, inscribed with their logo, marked the places where they laid sewers. They supplied structural steel for the earliest building projects that called for it, and giant prefabricated cylinders that became lighthouses, most notably in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, and at points along the Hudson River. And they laid the sewers in the new Dorchester neighborhood.

Mr. Smith’s son Bryant married Annie Procter, the daughter of the newspaper publisher in Gloucester, and a descendent of Massachusetts’ earliest Puritan settlers. Perhaps the expensive detail in the house was meant to impress her, to make her feel at home in a neighborhood yet to be acclaimed as prestigious. They began raising children in the house, helped by three servants.

The neighborhood never really caught on with the wealthy. The railroad tracks, built in 1850 for local service, became in 1885 a part of the New York and New England Railroad’s “air line,” a direct route for the fastest trains from Boston to New York. Every afternoon those trains—one into the city and one out—roared by the back of the Smiths’ house. They sold in 1889 and moved a block further from the tracks, to a mansion on the top of the hill across from their front porch. Then, ten years after that, the developer/entrepreneur who’d created Monadnock Street ended a voluntary moratorium on building and filled his remaining lots with cheaper houses. A wall of 3-deckers went up across from number 29, blocking the view to the top of the hill and the house where the Smiths had moved. More of the original owners sold and moved. When doctor owners who saw patients at home arrived, it was, in some minds, a serious moment of decline. Working class families owned and occupied the three-deckers by the time the street felt the Great Depression. That was when the Smiths’ house had an Irish immigrant owner who lost it to foreclosure.

Monadnock Street and Uphams Corner never really recovered from the Great Depression. And in the 1950s, removal of the trolley tracks from the main streets ended the neighborhood’s era as a transportation hub. Stores closed.

Decline continued through the 1960s, when the neighborhood experienced its first high-profile violence. In 1964, John Piotti, a record store owner, was murdered in his store. By 1970, Uphams Corner was in free-fall. The turnover of houses and apartments was accelerating like a train. Stories about the grand days of the past sounded like wild hallucinations. Store owners became hardened cynics. They locked their doors. The neighborhood had nothing going for it. Opinion leaders downtown said it was “gone.”

29 Monadnock Street – Bob Haas’s home since 1971. It was built in the 1870s for a wealthy industrialist. By the early 70s, it was a shell of its former self. Bob Haas photo

1. Getting In

When I first heard of Monadnock Street, it was an invisible place. None of the subways ran anywhere near it. But some friends wanted to buy a house there. They planned to fix it up.

They talked about the house every time I saw them, filled with excitement about how they would raise their son there and live in community with others. After resisting for some months, I took them up on their invitation to come and see. My visit, on a sunny summer afternoon, exposed me to the reality of the neighborhood, first to the noise on the street. Guys were fixing cars with their friends hovering around them, chugging beer from quart bottles. Teens were pounding basketballs on the pavement, while smaller kids, as young as 3 and 4, yelled and darted around them, on and off the sidewalk. Sometimes a car’s tires screeched for an emergency stop. Souped up car stereos completed the din, disallowing any silent pauses.

The house was massive, three stories with gables and a sweeping porch with wooden arches and spindles. It was the only one with a setback from the street, with a front yard and a driveway that ran under a giant beech tree.

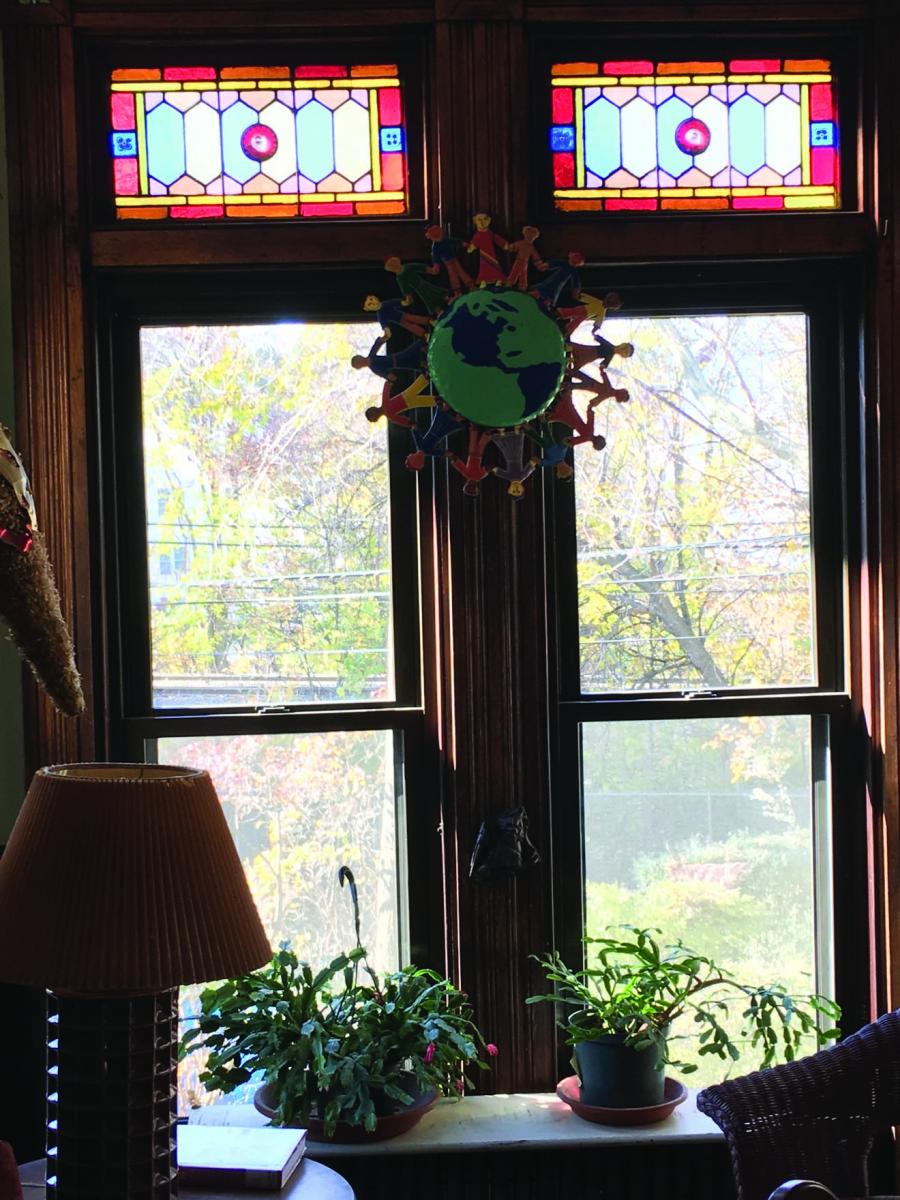

The inside was another world, a place of quiet. The noise didn’t penetrate through the broken, boarded windows, and the only light came from stained glass. Brightly colored transom panels, some of them marred by rock holes, remained uncovered. Where they passed through, the sun’s rays cast patterns of red and blue on the floor. I felt as if I’d entered a church.

That moment in the house pulled me in. On my tour of the rest of the house, I imagined its transformation. I began to share my friends’ excitement. With seven bedrooms and six expansive rooms on the first floor, all to be common space, this house could really be a harbor for community. The house became special to me. I wanted to see it saved, almost as much as my friends did. I volunteered on afternoons to come and paint and share dinner time. That was why, when some months later I’d lost my professional job and my career seemed to be derailed, I hoped I could move in.

I hadn’t lost my engineering job due to lack of competence, or out of failure to perform. I was good at what I’d been doing. Rather, political shifts in Washington had wrought a reordering of the Massachusetts high-tech industry, and with it a sudden spike in unemployment. More than 1,000 engineers were looking, during the Recession of 1969-1970, for new jobs. I wasn’t going to get hired right away, and if I told my parents in New Jersey, I knew I’d be nagged, especially by my mother, for my inadequacy, for my lack of initiative, for what I’d done to cause my plight. I was 26 then. I decided to hide what had happened to me. I would move into a community at 29 Monadnock, live cheaply there and survive.

As soon as I moved in, at the end of 1970, the house became the center of my life. I gave it my time, replacing the panes in broken windows and taking the boards off, painting walls and ceilings inside, climbing a 40-foot extension ladder to the third-floor gable, to scrape and put paint on wood trim that hadn’t been touched for decades. I wanted the house to be and look like a home. I spent most of the money I had reclaiming beauty that came to light once the boards were off the windows. I restored floors, carved fireplace mantels, tiles, and molded plaster. I fell into the pattern already set by my housemates -- we were too busy working on the house to talk to the neighbors. I hoped the restoration of the house, by itself, would be a signal to others that things would improve.

Windows at 29 Monadnock. Bob Haas photo

But Monadnock Street then was in deep decline. It was dangerous. It was battered. It had fresh scars where the skeletons of burned-out buildings still stood weeks and months after they’d burned, where piles of rubble remained behind after houses got knocked down. Some properties were kept up, still attractive, but they were the exceptions. Some yards, like mine, had giant shade trees and bushes. The wooded overgrowth along the disused railroad tracks served as a habitat for wild animals. I saw a pheasant there once. But as much as shady areas could be quiet, the trees and bushes were places to hide from the police. They were cover for fugitives, muggers, and housebreakers.

The only way to drive into Monadnock Street was from the business district on Dudley Street, an artery that most Bostonians tried to avoid. The storefronts there looked seedy, even where established, respected businesses were still operating. And four bars, with late night hours, attracted trouble. The biggest one, my choice of a landmark to guide visitors to my house, was the Pink Squirrel Lounge. It occupied a two story concrete structure, painted bright pink and adorned with flashing neon. Most nights it drew a collection of derelicts who drank on the sidewalk in front.

Drugs were easy to buy on Dudley Street. Heroin addicts desperate for a fix cruised up Monadnock Street, looking to break into houses and steal to support their habits. They fenced what they’d found back on Dudley Street, watches, jewelry, and small appliances, offering items to storeowners who mostly refused them.

Nearly every night I could follow the wail of fire trucks as they moved through the streets, toward some new destination. Most of the fires were across the tracks. First, the engines came from the local fire station. Then additional alarms sounded from other parts of Boston. Sometimes, if the fire was big enough, trucks came from towns outside Boston. Our local fire station gained the reputation for being the most active in the USA. Just about every night, something burned down. Smelling the flames and smoke and hearing the cries of people put out of their homes was everyday experience. So many fires, so often, couldn’t be accidental. The neighborhood’s stench, from charred wood, broken plaster and powdering mortar grew in intensity the more the devastation spread. The dust was everywhere. The visual images inhabited my dreams.

On Dudley Street, larger-scale fires consumed five and six-story apartment hotels, buildings with names like The Blackstone and The Normandy. After most fires, as soon as the next day, the City’s contractors moved in and demolished the skeletons of the buildings. Rubble from the bigger buildings, mounds of bricks, hunks of brownstone and mortar fragments, stayed on site. The piles brought out scavengers. I built up a brick collection behind my house, enough to lay out a patio. I also saved carved brownstone pieces, not knowing where I’d use them. I just liked the artwork. When visitors saw what I had, I told them the neighborhood was like the Roman Empire in its last days. I was gathering fragments from the ruins of Boston. Antiques dealers were usually the first to comb the rubble. They took away doorknobs, floor grates, mantels, whole doors and leaded glass windows, things they could resell at inflated prices, to customers unaware of what had produced the items.

When the fire of the night was just across the tracks, and the wind was just right, the smoke and sparks blew over into my back yard. My neighbors advised me to join them using garden hoses to water down our roofs, hoping to protect against flying cinders. No one could know how bad a fire would be, whether some night the fire would actually engulf some of our houses. That had owners on my side of Monadnock Street ready to sell, to anyone. They would take a loss. Some would give their house away. Any chance to get away.

I kept to my belief that things could get better if I just kept working on the house. In my first two years I stayed out of conversations with the neighbors. I didn’t want to have to try to answer their negativity, or speak to their panic. I could hear plenty of what they said from a distance. When I finally broke my silence, it was to talk to Larry, a young black homeowner. Larry lived in a three-decker across the street, and he was spending long hours and money to renovate it. I could see that he’d done beautiful work, and he seemed to be mostly finished. He seemed invested. I wanted him to be, like I was, a person who believed the neighborhood could turn around. I wanted him to be the kind of man who would stand firm, protect his property, and look for creative solutions to problems.

But his first words were, “Hi, I’m selling. When are you?” He described how he saw no future in Boston with neighborhoods like ours falling apart. He’d decided to move to Holyoke, in the middle of the state. I was shocked and disappointed by what seemed a sudden decision, just after he’d finished his work. I tried to talk him out of it. I tried to tell him about my own renovations and my commitment for the long haul. I begged him to hear me out, but he wouldn’t.

It seemed as if Larry had sought me out for his announcement, as if he wanted me to affirm his decision. But I wouldn’t. By that time I’d become fully embedded in what I was doing. I’d bought out all my co-owner friends. Larry’s refusal to invest, his refusal to hear my words, made me understand that just fixing my house wouldn’t be enough. That wasn’t going to stabilize the neighborhood. I would have to do more to be able to last in the neighborhood, and I didn’t know what it would be. What would I have to do, what would have to happen, so someone like Larry would want to stay?

***

The work that Bob Haas has done to help preserve and uplift his Uphams Corner neighborhood has extended far beyond his front porch. He has been a central figure in the revitalization of the business district and surrounding streets and in the efforts of two pivotal forces for improvement: The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) and the Dorchester Bay EDC. He has also been a witness— and sometimes a victim— of violence, arson and tragedy in his 47 years on Monadnock Street.