March 2, 2017

Boston’s public schools are in line for a massive overhaul in the next decade, with the majority of facilities in need of some repair and changing educational standards expected to push the limits of the district’s existing building capacity, according to a city report released by Mayor Martin Walsh on Wednesday at the Boston Municipal Research Bureau’s annual meeting.

The document is the culmination of more than a year of work under the BuildBPS initiative, the city’s 10-year educational and facilities master plan.

In an early briefing to reporters on Tuesday, city and school officials emphasized that the report, which includes an online interactive data tool, was not a prescription for dramatic change.

“Build BPS is not a list of school closures and it is not a list of specific school projects we want to do moving forward,” said Ben Vainer, director of strategic initiatives for the mayor’s education cabinet.

Rather, he said, the data are the guide as the district and community members determine what repairs, expansions, or new construction will be merited in the next decade.

Officials said the school anticipated an increase of up to 2,000 students in the system over the next few years.

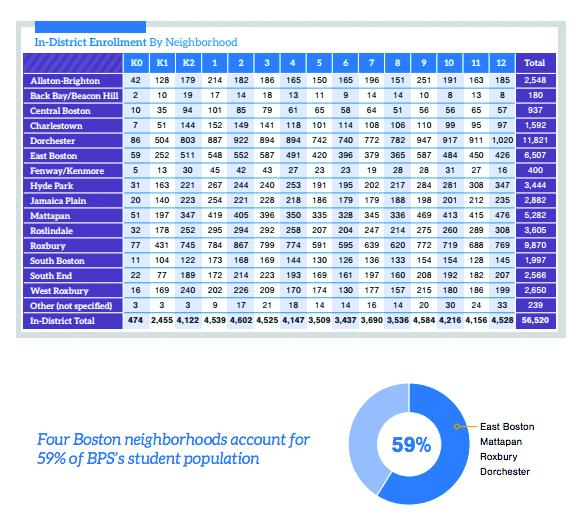

East Boston, Mattapan, Roxbury, and Dorchester are home to 59 percent of the city’s school-aged children, the report says, noting that “the projected percentage of growth is also highest in these neighborhoods for the foreseeable future.”

School capacity is being recalculated in the BuildBPS plan. As classrooms and schools are laid out now, the district can house about 69,000 students, filling the schools to about 81 percent capacity. This calculation accounts for the traditional classroom setup, with rows of neatly packed students facing an instructor at the front.

Contemporary education demands more flexibility in classroom arrangement, availability of creative space, and room for a peer-to-peer learning environment, school officials said. Rooms would need to be enlarged, and some re-allocated for music and arts spaces. That lowers capacity by about 10,000 seats, which is not quite enough to house all currently enrolled students if all schools were reconfigured to meet that standard.

In discussing the need for a longer-term plan for funding crucial school repairs and renovations, Boston’s Chief Financial Officer, Dave Sweeney, said they “found that school investments have historically been done on an ad hoc basis.”

Walsh pledged a $1 billion investment over 10 years in the system’s buildings and classrooms in January, a move that Sweeney said will allow the city to take the long view of school infrastructure.

The district has a very old structural base – 66 percent of the buildings haven’t been renovated since World War II. About half of the facilities are in “fair” condition, the assessment found, a conclusion borne out in surveys and public meetings.

“What we talked with the public about is what are their experiences right now with their schools,” Vainer said, “which we found very much echoes what the data tells us, which is that our schools need a lot of love. And it also told us that overall families are happy with the instruction happening in the school and just wish there was a better building to support that.”

The BuildBPS system for evaluating building standards uses four measures. Assessments grade the physical condition of the buildings and the quality of the sites. The building’s effectiveness as a learning space is measured by its characteristics and contents, as well as by state standards for space shape and size.

Many schools are weak in multiple facilities measurements, though in some cases they are counterbalanced with particularly strong characteristics. The Edward Everett elementary school, for example, ranks “fair” or “good” with regard to the actual site, but ranks “poor” in learning environment and “deficient” in the space assessment. The Dever School is “fair” in three measures, but the building condition is considered “poor.”

The Mattahunt Elementary School, which will be closed and re-opened as an early learning center this summer after consistently poor academic performance, highlights the balancing act between facilities assessments and educational standards.

The Mattahunt’s building and learning environment is, for the most part, fine by the BuildBPS measures. In structural quality, it is “excellent,” having received bolstered funding as the district attempted to reverse its low performance status.

For parents, who now have additional school quality measurements to sift through, building quality and academic strengths will continue to be assessed individually.

“We’ve separated academic quality from the integrity of the building,” Dorsey said. “We’re just going to have to be clear to make sure to say to parents, ‘These are two different sets of measures.’ When we’re looking at quality and state accountability, that is really a separate conversation from what we need to fix in this building… and one doesn’t preclude the other.”

The school facilities department, until now the only such department to operate separately from city facilities as a whole, will be absorbed by the Public Facilities Department.

BPS plans to launch new conversations with the community starting with March and April informational sessions to introduce residents to BuildBPS and gather feedback. After that, there will be neighborhood workshops in May to begin using the facilities data to set district priorities. About $13 million is allocated for new technology and funding for immediate fixes is included in the current year’s budget.

The interactive dashboard is available online at BuildBPS.org.

Topics: