April 17, 2014

Darrell Ann Gane-McCalla : Collage contrasts coverage of neighborhood violence with marathon. In the midst of ramped up coverage of the Marathon and the Marathon bombing tragedy, a small group of Boston area artists gathered near the Boylston Street finish line on Tuesday evening to raise a contrarian view about the meaning of the slogan “Boston Strong” in the context of neighborhood violence.

Darrell Ann Gane-McCalla : Collage contrasts coverage of neighborhood violence with marathon. In the midst of ramped up coverage of the Marathon and the Marathon bombing tragedy, a small group of Boston area artists gathered near the Boylston Street finish line on Tuesday evening to raise a contrarian view about the meaning of the slogan “Boston Strong” in the context of neighborhood violence.

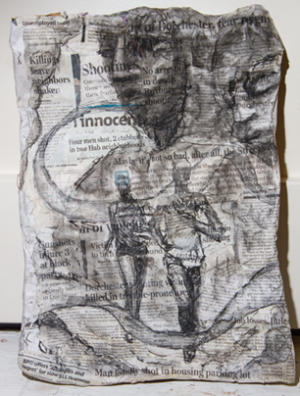

Darrell Ann Gane-McCalla, a former Dorchester resident, was one of three artists to put together a show called “Boston Strong?” to spark discussion about the coverage of the Marathon bombings and the comparative lack of coverage of the victims of crime in the city’s neighborhoods, including Dorchester.

“One thing about my work is it is making commentary about how our culture is pretty violent in general with terrorism or domestic violence or street violence,” Gane-McCalla said.

Her piece, in which drawings of people covered newspaper articles of violent events, stood beside those of artists Shea Justice and Jason Pramas at the Community Church of Boston’s Lothrop Auditorium at 565 Boylston St., one block from the Boston Marathon finish line in Copley Square.

The three artists held an opening event Tuesday with remarks by former Boston mayoral candidate Mel King, Tina Chery of Dorchester’s Louis D. Brown Peace Institute and hip hop poet Ant Thomas. A few dozen people attended.

Thomas, who is also a legislative aide to state Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz, D-Boston, performed a poem called “Shackles,” exploring the idea of how the shadow of slavery still affects the mentality of black youth today.

Thomas said he achieved success in his life, but that it is a difficult thing to do for black people.

“There are clear discrepancies that discourage our young people from being successful,” Thomas said. “When you’re constantly seeing on the news that you’re the only people on food stamps, that you’re the only people that commit crime.”

Thomas pointed out that six companies gave $1 million to the One Fund, the account set up to support the victims of the Boston Marathon tragedy, while victims of city violence remain unsupported.

Chery said it was important that the dialogue begun by the art exhibition continue well beyond Marathon Monday. Many people ignore violence in city neighborhoods because they feel separated from the crime, that it only takes place in “those” neighborhoods, Chery said.

She added that she felt that way, too, until her own 15-year-old son Louis got caught in the crossfire of two gangs while walking to the Fields Corner T station on Geneva Avenue in 1993. Questions came at her asking if her son, an innocent bystander who was killed by the gunfire, was in a gang and dealing drugs.

“I felt what many of ‘those’ people felt – a sense of life less worthy,” Chery said.

Chery said the fact that so much support went to the Boston Marathon Tragedy and the One fund gives her hope, because it means that people are caring. The challenge is to communicate the tragedy of the continuing violence in Boston.

In the past month, there have been four homicides in Boston, according to Chery. One family has had to postpone the funeral of their son because they could not raise the $4,800 necessary for the burial.

“So we’ve got work to do,” Chery said, stating that her organization has set up a fund for the families of victims of violence.

Contributions to the fund can be sent to the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute, 1452 Dorchester Avenue, 3rd Floor, Dorchester, MA 02122-1386.

King, a longtime activist who was a mayoral finalist in 1983, talked about the power of dissent to create change. He told a story of remaining silent during the Pledge of Allegiance while a student in high school.

“The instructor was furious, and he said, ‘With all we’ve done for your people,’ and I said ‘Slavery,’” King said.

It is important to share the message of the “Boston Strong?” exhibit – that there is lots of attention and public support for the Marathon bombing tragedy, which affected many white people, but there is a lack of support for neighborhood violence that affects mostly people of color, King said.

And it is important to use that message to mobilize change, he said.

“Failure to do so means you are locked up, locked in,” King said. “And that’s a very painful place to be.”

Chery concluded by asking those in attendance to move forward and keep the conversation alive.

“This intimate gathering will fuel us to take away the question mark from the Boston Strong and to say it is Boston Strong simply because the artists found the courage to have this conversation,” Chery said.

Audience member Tara Alves of Framingham said she was happy that people spoke of making something constructive out of the tragedy and the discord.

“I’m really happy to be here,” Alves said. “I felt this was very moving and I hope everyone here finds some sort of healing before they leave here today.”

For more information about the exhibit, visit questionbostonstrong.com.

Topics: