September 4, 2013

Larry DiCara memoir: Co-authored with former reporter Chris BlackIt’s the rare political memoir that earns a place in the Boston canon before it’s even sent to the printer. It’s rarer still when its author’s name hasn’t appeared on a city ballot in three decades.

Larry DiCara memoir: Co-authored with former reporter Chris BlackIt’s the rare political memoir that earns a place in the Boston canon before it’s even sent to the printer. It’s rarer still when its author’s name hasn’t appeared on a city ballot in three decades.

But Larry DiCara has frequently defied convention in his half-century turn on Boston’s political stage.

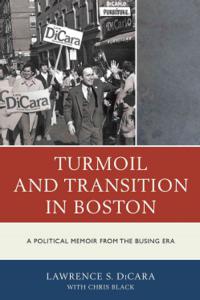

His new book, “Turmoil and Transition in Boston: A Political Memoir from the Busing Era” focuses on his years as a member of the Boston City Council— from his 1971 election as a 22-year-old reformer to his fourth-place finish in the 1983 mayoral race. As the subtitle suggests, DiCara offers a refreshingly candid insider’s take on the school desegregation crisis that roiled the city throughout the ‘70s and beyond. DiCara finds ample fault on both sides of the busing divide and, in doing so, steers a course towards a more nuanced, mature, and accurate understanding of the era – a time when Boston damn-near scuttled its own ship.

A first-generation Italian-American who emerged from Dorchester’s then-Irish-dominated Ward 17, DiCara retired from politics after placing fourth in the 1983 preliminary election for mayor. During his stint on the council, DiCara became a master of the often mundane – but always essential – machinery of city government. Today he is one of Boston’s most respected and wired attorneys – particularly sought-after by clients with business before the city’s various review bodies, such as the Zoning Board of Appeals.

DiCara’s loss in the 1983 contest was a disappointing finish for a wunderkind who was elected to the council at age 22. A Boston Latin School and Harvard graduate, DiCara was the first baby-boomer to win a spot on the council. His unexpected 1971 victory buoyed the earnest and ambitious pol’s dream of becoming the city’s first mayor of Italian descent.

A proud progressive in the tradition of one of his political heroes, New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, DiCara was noted for his early support for gay rights and for aggressively courting voters in marginalized black precincts. Yet he was also old-fashioned in his own immigrant boot-strap way: a straight-laced, frugal, bookish kid who hawked newspapers outside of St. Gregory’s Church and who recoiled at the sight of elderly gamblers who’d blow their Social Security checks at the weekly parish hall-turned-gambling parlor. He was even more offended by the hackneyed, wink-and-a-nod antics of the petty pols who dominated his era in City Hall. (Think Albert ‘Dapper’ O’Neil, the often vulgar at-large councilor whom DiCara had to tolerate as both a colleague and constituent.)

DiCara cultivated a coalition of voting blocs that propelled him onto the council – and once helped him top the citywide council ticket – but that proved to be an ultimately unsturdy rung on the climb to higher office. In retrospect, DiCara chalks some of his career setbacks to bad timing: He quickly found himself out of step with large chunks of his base, who were sharply split over the court-ordered desegregation plan. DiCara identified with the plight of black school kids and understood that the path to the 1975 flashpoint crisis was cobbled together – stone by stone – by the intransigence and dead-up bigotry of many voters and their elected officials.

But like many moderates, and even some progressives of the time, DiCara was also a sharp critic of the plan ordered by US Judge W. Arthur Garrity to remedy Boston’s blatant segregation in its schools. DiCara preferred a compromise plan drafted by former state Attorney General Edward McCormack to the Garrity-sanctioned scheme that ultimately prevailed. The Garrity plan, authored by two Boston University professors, “pitted the poorest white neighborhoods against the poorest black neighborhoods” with predictable consequences, he writes. (DiCara himself tried to advance a “metro” approach that included suburban communities, a non-starter both then and now.)

Despite his reservations about the judge’s plan, DiCara was singular among Boston city councilors in avoiding the more radical elements of the anti-busing movement. He eschewed any outward signs of support for the “Restore Our Alienated Rights” (ROAR) group that came to define the mainstream white opposition to the busing plan. While DiCara acknowledges that he was “no profile in courage,” his aloofness cost him votes and, perhaps, hobbled his more lofty ambitions for statewide office or the mayor’s perch on the Fifth Floor.

He writes, “People whom I had known my entire life refused for the first time to post one of my campaign signs in their front yards. Neighbors looked me in the eye and said they could not vote for me. The bad feelings from that campaign lingered so long that some old neighbors from the parish have not spoken to me for nearly 40 years.”

DiCara’s book offers keen insights into a bygone Boston without the hard-to-swallow nostalgia that sometimes seeks to mask our lesser tribal roots as some backwards badge of honor. The author discerned at an early age that the irrational fears of “the others” remained a powerful force in a city with a long history of ethnic division. One of his great contributions to city government was his role in changing the city charter to adopt district seats, thereby assuring more diverse representation on Boston’s governing body.

In an afterword, DiCara marvels at the demographic changes that began to show during his time in office and now portend the possibility of a first-ever mayor of color, perhaps as soon as January 2014. But DiCara has learned to keep his powder dry when it comes to making any hard-and-fast predictions about election outcomes. He is content to lean back on the sage observations of Dot-bred journalist Theodore White, who wrote: “There is an ethnic ballet, slow yet certain, in every big American city that I have reported, which underlies its politics.” In his memoir, Larry DiCara reminds us that Boston’s ballet is capable of some unexpected encores.