February 1, 2012

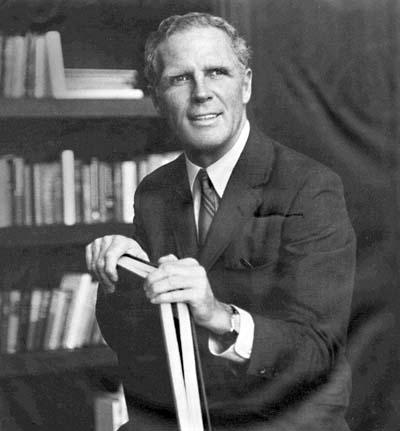

Photo courtesy of City of Boston archives

Kevin Hagan White was a man of many personas – ebullient, moody, haughty, energetic, fretful, intellectual, daring, to name a few ascribed to him during his often-tumultuous mayoral occupancy of Boston City Hall from 1968 through 1983.

White, who died on Friday, Jan. 26, at age 82, took what his immediate predecessors, John B. Hynes and John F. Collins had begun – the rebirth of a Boston that some had come to call decrepit – and added his own imaginative flourishes as the city of the Brahmins regained its long-held place among the nation’s and the world’s great cities.

But along with those flourishes came great stress and heartache, perhaps most notably the deeply felt unrest in the mid-1970s over the busing of students across neighborhood lines under a federal judge’s order aimed at ending the racial imbalance that the court had found entrenched in the city’s school system.

To hear former City Councillor Lawrence DiCara tell it, Boston was on its knees when Kevin White strode into City Hall in 1968.

“The majority of my contemporaries were bolting from Boston— and this is before the desegregation order,” DiCara recalled this week. “There was a massive exodus of people. We had Time magazine calling us the New Appalachia. And we were being compared to cities like Cleveland and Detroit.”

William M. Bulger, the former state Senate President, UMass president and political contemporary of White’s from the early 1960s, praised White’s devotion to the city and his cheerful nature.

“Kevin saw the political life as a noble profession,” said Bulger. “I think that he was always conscious of the fact that his own dad, Joe White, had been active in it and Kevin had a very high opinion of his dad. He brought to the task an enthusiasm that inspired many of us who were around him.”

White’s reputation as a “downtown” rather than a neighborhood mayor was deserved, especially towards the latter part of his 16 year tenure, DiCara said.

“He had grown very impatient with neighborhood meetings,” said DiCara. “There had been so many around the time of desegregation. He decided he’d do what he did best and the end result was pretty good.”

Still, DiCara says that White, who served until 1984, remained central on major development issues throughout the city’s neighborhoods. He factored heavily into the 1970 decision to locate UMass Boston on the Columbia Point peninsula, DiCara remembers.

The city’s current BRA chief Peter Meade once served as White’s parks commissioner and coordinated public safety during the busing crisis. Meade pointed to a number of public buildings built in Dorchester while he was mayor: the Gibson St. Police station, the Lee School, the Murphy School, the Holland School, and the Marshall School. White also oversaw the restoration of Franklin Park.

Mayor White relied heavily on a cadre of Dorchester activists and city workers who stayed loyal to him — even through two bruising election challenges from his longtime rival Joseph Timilty, a state senator who hailed from Lower Mills.

“Kevin knew he couldn’t beat Joe in his own backyard, but he always competed,” DiCara said. “I can remember joking with Bobby White— who was in charge of running the southern part of Ward 17 for the mayor’s re-election— that we had run out of kids to give summer jobs to.”

One of White’s key lieutenants from Dorchester was Eddie Sullivan, who served as White’s “vice-mayor” during the 1970s. It was Sullivan who would frequently run interference for the mayor with councillors like DiCara— polling them on tough votes coming before the council.

“Kevin trusted him like a big brother. I can recall him coming to me one time and saying, ‘Larry, we really want your vote on something.’ I can’t even remember what it was now. But, I told him, ‘I’m not sure, Eddie.’ And he said, ‘Is there anything we can do to convince you?’ I said, ‘Sure, how about building us that new library we’ve waiting for in Lower Mills?’”

Within two years, Lower Mills had the modern, new library it had been clamoring for on Richmond Street, replacing a smaller, quaint library just down the block.

“The morale of story, I guess, is that Mayor White cared enough about Lower Mills to make sure we got that new library,” DiCara said.

Another city councillor from the White era, Bruce Bolling, called the former mayor’s legacy “mixed.” Bolling ran as one of “Kevin’s Seven,” a slate of candidates backed by White, and he was the only one among the candidates who won in 1981.

“He was a visionary in the city, no question about that, and he was the primary stimulant for downtown development, the creation of Faneuil Hall as we know it now, waterfront development,” said Bolling, who also worked in the White administration. “A big blemish with Kevin White was the school desegregation process, but that blemish was not his alone. That was a stain on white leadership in the city as a whole at the time, because nobody stepped up to the plate to address school desegregation in any responsible way.”

City Councillor Charles Yancey, who was elected to the City Council at the tail end of White’s tenure, agreed when asked about White and his handling of court-ordered school desegregation.

“He had to deal with very conflicting interests,” said Yancey, who was elected in 1983. “I think it’s fair to say he could’ve done more in terms of addressing the issue, but I think the city was for the most part well served by what he did do and his efforts to reach out to all the communities and deal with the frustration many felt.”

The era that White came from is gone, according to state Rep. Marty Walsh, who recalls attending a political rally when he was seven years old and supporting Timilty.

Politics is much more personal these days, Walsh said. In the White years, the mayor and Boston’s State House delegation clashed frequently, he acknowledged.

“They had grueling battles but they were able to move on,” Walsh said.

Bulger, who frequently disagreed with White on issues like the enforcement of the controversial busing order in South Boston, said that White remained level-headed and professional throughout such racially-tinged crises.

“We would go down to City Hall frequently and we were on the same wave-length pretty much all the time,” Bulger recalled. “It was, how do we get through this and have everything intact at the end of the effort. There was a maturity and trust for the other person. He was always very kind to me in his public utterances.”

City Council President Stephen Murphy got to know White later in life, after White was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. He would accompany White and their mutual friend, former state Treasurer Bob Crane to lunch.

Murphy remembers giving White rides back to Beacon Hill, and White asking how the city was doing during the economic downturn.

White began “the process of bringing Boston into the twenty-first century, Murphy said.

Murphy also pointed to the able staffers he hired, including Barney Frank, who would go on to become a Congressman. “He brought great young talent to City Hall, and he was not afraid to let the talent run on their own,” Murphy said. “He was never afraid of giving credit where credit was due or sharing credit, which is big when you’re in elected office. He was a different breed.”

Meade said White “changed the mold of City Hall,” turning it from an enclave of largely white Irish males to a place with “people from all over the city,” and women playing a prominent role.

White looked for people who could come from either end of the Red Line, Meade said, whether they were lecturing at Harvard University or going to the Cedar Grove Civic Association.

“He didn’t have a mold where he expected that talent to come from,” Meade said.

For Joyce Linehan, an Ashmont resident who was born and raised in St. Brendan’s parish, Kevin White’s administration will always be the one that introduced her to the arts— which eventually led to her current career.

“Mayor White’s Office of Arts and Culture established ‘Summerthing,’ which presented hundreds of great concerts, performances and workshops, featuring big name national as well as local artists,” Linehan said. “I remember them being all over the place - in town and in the neighborhoods, in existing spaces.

“In the late 60s and early 70s I spent many a summer afternoon in Dorchester Park taking advantage of the arts-heavy Parks and Recreation program. It definitely colored my view, made my world a lot bigger, and I’d say set me on a particular career path,” said Linehan, who works as a publicist and promoter. “[Mayor White] clearly understood the power of the arts as it pertains to all kinds of issues - urban development, racial tension, economics and more.”

Bulger believes White will long be considered one of Boston’s best mayors.

“I just wish everyone in the political realm or thinking of it would know people like Kevin White, who gave his whole life to the task,” Bulger said. “He was an extraordinarily good person and always attentive to the task. There were no days off for Kevin.”

CORRECTION: Due to an editing error, the headline incorrectly stated the year of White's birth. It is 1929.