December 27, 2012

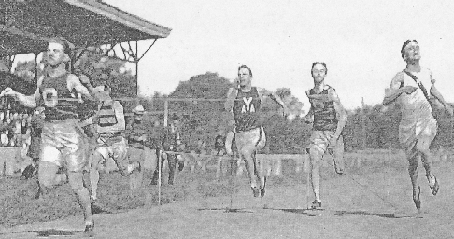

Arthur Duffey, left, set the world record in the 100 yard dash in this May 1902 race captured by photographer W.N. Jennings.

On May 31, 1902, 22-year-old Arthur Francis Duffey, a Bostonian with ties to the city’s Roxbury and Dorchester neighborhoods who was at the time a student at Georgetown University, burst from the starting line of the 100-yard sprint in the national intercollegiate track and field championships at the Berkley Oval in New York City and hit the tape 9.6 seconds later, in the process lowering the world’s record from 9.8 seconds. Duffey’s time earned him the designation of “world’s fastest human”; it was a number that would not be bested for another 28 years.

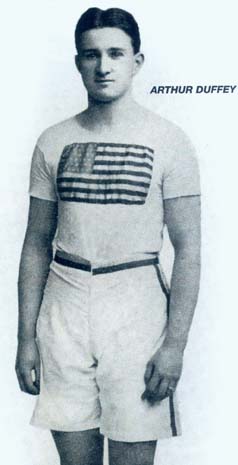

In the half decade comprising the last years of the 19th century and the first few of the 20th, an era when amateur sports dominated newspaper coverage, the name Arthur F. Duffey stood for sturdiness of purpose and excellence of accomplishment. During those years, he competed, and won, across the United States and he traveled to Europe and Australia, where he was regarded as a running superstar. “King of the English Sporting World” read the headline over a Boston Globe story about Duffey’s win in a July 1902 race held in Sheffield, England.

Then, in November 1905, the run was over; all of his records were ordered erased in perpetuity by a national amateur track organization, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), in the wake of never-confirmed reports about sponsorship money and improper dealings with a shoe company. As far as the formal world of amateur sports was concerned, Arthur Duffey had never run a race in any of its competitions. The public record of the time shows that for many track fans, the case was one where a zealous rectitude had prevailed over fairness and any sense of justice.

***

Arthur Duffey: Inducted into USA Track and Field Hall of Fame — more than 100 years after his career ended.There was minimal public notice given locally – a few lines in a Globe sports pages update on Olympic matters –to a ceremony held in Daytona early this month where Arthur Duffey was inducted into the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame. But to Arthur Duffey’s descendants, the induction was the resurrection of man and his reputation as a runner without peer in his time, something that he and they had been seeking for more than 100 years.

Arthur Duffey: Inducted into USA Track and Field Hall of Fame — more than 100 years after his career ended.There was minimal public notice given locally – a few lines in a Globe sports pages update on Olympic matters –to a ceremony held in Daytona early this month where Arthur Duffey was inducted into the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame. But to Arthur Duffey’s descendants, the induction was the resurrection of man and his reputation as a runner without peer in his time, something that he and they had been seeking for more than 100 years.

***

There is a case to be made that Arthur Duffey initiated the proceedings against himself. Shortly before the AAU’s erasure of his name and records in late 1905, he had written an article for a magazine that seemed to suggest that he had received expense money while competing as an amateur, which made him a professional in the eyes of the AAU and others.

In following the story, the Globe quoted him a few days later as saying, “If they thought that my story would end with a rehearsal of my own doings, they’ve shot wide of the mark. That was only the beginning. I know how the crooked game is played from start to finish. I know the men who have yielded to the temptation and thus violated both the spirit and the letter of all amateur rules.”

The meaning of Duffey’s words to the Globe have been taken in various ways: perhaps he was saying he went over the line, or maybe the point was that while he was very much aware of the “temptations,” he didn’t participate but would tell the public what parties were doing what.

In his 2010 book, “The End of Amateurism in American Track and Field,” Joseph M. Turrini writes that the AAU, in the person of an official named James Sullivan, stood firmly behind its decision to deny Duffey any recognition, with Sullivan saying to an interviewer: “When an athlete breaks an established law, a trial is not necessary. He has disqualified himself.”

The AAU statement announcing its decision was stark in its brevity: The organization was eliminating “every mark of distinction with which Arthur F. Duffey has been credited, these having been made on the assumption that he was an amateur, as evidenced by the signing of entry forms, etc.

“This determination by the committee displaces the following records: Forty yards (4.6 seconds) made Feb. 13, 1899, March 4, 1899, and Feb. 10, 1900, in Boston; Fifty yards (5.4 seconds) made Feb. 21, 1904 in Washington; Sixty yards (6.4 seconds) made Nov. 30 and June 7, 1902, in New York City; One hundred yards (9.6 seconds) made May 31, 1902, at Berkley Oval, New York City.

“While in every instance above mentioned, with the exception of ‘the hundred,’ Duffey held the records jointly with others, the ‘century’ mark of 9.6 seconds stood in a class by itself. By displacing this performance as best on record, the 9.8 seconds [held jointly by five others] now stands as the topmost mark at 100 yards.”

Over the next 15 years Duffey and his family and associates pressed for a hearing so that he could lay out his entire story, at one point suing for the opportunity. But, writes Turrini, a court ruled that the “AAU was a private organization and an athlete judged by it has no recourse.” Finally, in 1920, the AAU did take another look at the case, according to Turrini’s account, but it was reported that the Sullivan files had been lost in a fire, so the burden of proof was on Duffey to make his case – after he posted a $350 bond. He declined to proceed and so the matter stood for all practical purposes until the USA Track and Field ceremony this month.

***

Pursuing his cause across the years was hardly the only thing Arthur Duffey was doing. He kept up with his passion for athletics by working for almost 40 years on the sports staff of the now-defunct Boston Post, the city’s largest-circulation paper over the first half of the 20th century, and by coaching track at both Boston College and Boston College High School for a time. He also left Dorchester for Arlington where he raised a family of three sons and a daughter with the former Helen L. Daley of Neponset.

In talking with pride of his grandfather on the occasion of his Hall of Fame honor, William Duffey, the proprietor of Regal Press in Norwood, took note of how the notion of speed has carried the day in the family over the years. “In the Harvard Interscholastics of 1933, my uncle, Arthur Jr., was running in the 100-yard sprint for Exeter and he tied the competitive record time that had been set 33 years earlier – by his father.”

***

The parsing of amateur versus professional, in particular in track and field, that obtained with utmost stringency 100 years ago is now a part of history, the NCAA’s uneven and often mismanaged efforts at holding to a standard notwithstanding. The day of amateur sports organizations scouring the landscape for missteps by young athletes just trying to make their ways in highly competitive activities are mostly gone. Those who play the games have won out over those who so long controlled their lives from behind their office desks.

The AAU and the NCAA fought for years over which group would get to approve individual credentials for the Olympic Games, the Valhalla of track and field competition, often leaving athletes to cope with a morass of competing regulations. Until 1978, the AAU had the hammer and used it to control all eligibility for the Olympics. That year, the Olympic and Amateur Sports Act made the AAU/NCAA competition moot, and gave the new United States Olympic Committee the right to set all the rules and and regulations concerning amateur sports in the US going forward with guidance from individual governing bodies of each Olympic sport.

What would Arthur Duffey and James Sullivan have made of all this?

Tom Mulvoy is a former managing editor of the Boston Globe and a native of Dorchester.

Topics: