November 7, 2012

Lawrence O'Donnell, OFD: His nightly program "The Last Word" has become must-watch television for progressives hungry for a left-wing voice of reason. Photo courtesy MSNBC

Lawrence O'Donnell, OFD: His nightly program "The Last Word" has become must-watch television for progressives hungry for a left-wing voice of reason. Photo courtesy MSNBC

When the hour came to name Barack Obama as the winner of Tuesday’s presidential election, Rachel Maddow had the honor of making the announcement for the cable network MSNBC. But it was Lawrence O’Donnell— the accidental news anchor and pundit sitting two chairs away— who was called on to put the finest flourish of a writer’s touch on the moment.

Instead, as cameras panned the crowd of jubilant Obama supporters in Chicago, O’Donnell had a suggestion: Let’s watch this crowd enjoy the moment of victory.

As the hour grew late, with a Romney concession inevitable, O’Donnell found words to put the president’s historic achievement in perspective. Despite a sluggish economy and anemic jobs growth, he had managed to fend off a vigorous challenge from Mitt Romney:

“It’s about an extraordinary candidate. A candidate the likes of which I have not seen in my adulthood.”

O’Donnell, who anchors the weeknight 10 o’clock hour for MSNBC, cable’s unabashedly left-wing news and punditry channel, has reached a new height of celebrity in this election cycle. His program, “The Last Word,” has become must-see programming for the Obama generation. More than any one TV personality, O’Donnell synthesized the argument for a second term into a nightly bundle that gave aid, comfort, and informed talking points to a restless base.

“He calmed me down. He became my weathervane through all of that,” says Michael Patrick MacDonald, the author and activist who now lives in Dorchester. “He’s willing to be critical of the left when there needs to be – speaking truth to power. But Lawrence got a lot people like me back on board with the president.”

One of the reasons that O’Donnell speaks so powerfully to the ears of people like MacDonald is that O’Donnell is — to steal from a certain campaign slogan — “one of us.” He’s a Dorchester kid who got kicked out of Catholic Memorial for being an all-around punk, who was pummeled in the Combat Zone by rogue Boston cops, and who didn’t give a rat’s ass about politics until he found himself working for an iconic US senator on Capitol Hill.

Even now— as one of the country’s marquee news analysts and partisan warriors— O’Donnell isn’t quite sure how it all happened. He’s also not sure if this nightly routine of bringing a garden hose to the mouths of the thirsty left is worth all the effort on his part.

“Every single thing I’ve done occupationally has been by accident,” he said over the phone from a storm-ravaged and gridlocked New York City last week. O’Donnell lives in Los Angeles, where he works as a screenwriter and actor; but since launching The Last Word in 2011, he is in New York four days a week to produce the show. “I never asked to do a show. I’ve been cancelled more than anyone else on cable television. It’s just that no one’s really noticed.”

•••

Lawrence O’Donnell, Jr., and his four siblings came of age in the 1950s and 60s in St. Brendan’s Parish. The O’Donnell clan bounced around from a three-decker on Gallivan to a two-family on Hilltop before finally landing in a single-family house on Grayson Street, two blocks from St. Brendan’s church and the grammar school that the kids all attended. It was then, as now, an enclave of Irish-Americans whose world revolved around the parish school, church and— more often than not— a public sector job.

O’Donnell’s own dad, Lawrence Sr., was a patrolman before turning to another dimension of legal life: Using the GI Bill, he put himself through Suffolk University and the-then unaccredited Suffolk Law School at night to become an attorney. Even after his father left the BPD ranks to build his own thriving law practice, Lawrence was surrounded by role models with badges— men named Walsh and Moran— who “were real authority figures around us all the time."

“My neighborhood then had a bunch of cops in it who were the fathers of my friends. They were the toughest and scariest fathers in the neighborhood. I look back on them very fondly,” he says. “We were the kind of kids who needed to be afraid of something. The simple honor of not breaking the rules was not good enough for us.”

O’Donnell and his brothers, it turned out, needed more policing than they thought. The Christian Brothers of Catholic Memorial, fed up with their juvenile antics, dispatched Lawrence and his brother Bill (along, he says, with about 40 of his classmates) one year in an epic bloodletting of “wise guys.” Furious, their parents exiled them to a private boarding school for a three-month stretch before Lawrence’s “pleas for a pardon” were answered.

The boys landed at St. Sebastian’s, a Catholic day-hop academy then situated near Brighton’s Oak Square. At the dawn of the 1960s, St. Sebastian’s was a school for hard-cases like Lawrence and Bill O’Donnell, and it served them well.

“It was a quirky, idiosyncratic place, and that was the magic of it,” says Lawrence. “It was inadequate in every way, but when they wanted to move it to Newton years later, all of us were opposed to it. I actually think a certain amount of imperfection is where you find the charm and magic of institutions.”

When O’Donnell was accepted to Harvard— where he flourished as a writer and humorist— it was, well, “awkward,” he says.

“At that time, people in Dorchester did not say, ‘Where are you going to college?’ People would say, ‘What are you going to do next year? I found it very awkward to say ‘I’m going to Harvard.’ None of us knew anyone who went to the college. I’d never seen the campus. I had seen Harvard stadium and my grandmother lived in Cambridge, so we’d take the Red Line and then the trolley to North Cambridge.

“The awkwardness of it is, ‘Hey, don’t think you’re so great. If you hit a home run in our neighborhood in those days, when you crossed the plate, you’d hear, ‘Why didn’t you pull it to left field?’”

Still, O’Donnell acknowledges, “The burden was on me, not anyone else, for my awkwardness.”

After college, O’Donnell tried his hand at teaching and became a substitute in the Boston public schools in the run-up to the busing crisis of 1974-75. He taught at a wide array of schools, including Girls Latin Academy in Codman Square. The experience not only inspired his first magazine article, published in Boston Magazine in 1980, but it forged his thinking on public education for life.

“It made me think in terms of the individual faces I’m seeing in front of me and which of these kids can be saved,” says O’Donnell, who today serves as a board member for a Dorchester school, Codman Academy.

Meg Campbell, the school’s founder and executive director, was a Harvard classmate and friend— and O’Donnell has made the innovative charter public school (which will dedicate its new building later this month) his top local cause.

“It means a lot to have him have our back,” says Campbell. “He’s a Dorchester guy through and through and it shaped his sensibility. He’s very real. He has this sense of regular people and what’s right and wrong.”

That moral compass was forged in the neighborhood, of course, but more specifically in the tight O’Donnell family unit that still bore the wounds of tragedies endured by earlier generations. O’Donnell’s grandfather killed himself after a family dispute at their home near Franklin Park in the 1920s, leaving a young family to fend for itself. The experience clearly left an indelible mark on the O’Donnells, who found solidarity with families, even those from different races, that knew the trauma and hardship that followed such a loss.

•••

The trajectory of O’Donnell’s life — and that of his family — was changed forever in 1975 when his father decided to take on a racially charged wrongful death lawsuit involving the Boston Police Department. James Bowden, a husband and father of two, had been gunned down on a Mission Hill side street that January by a pair of Boston cops who presumed he was a robbery suspect. He wasn’t. And the cops’ account of how and why they opened fire on Bowden didn’t pass the smell test — even though the BPD’s perfunctory review of the incident had cleared them of any wrong-doing. When Bowden’s widow came to seek Lawrence O’Donnell, Sr.’s, counsel, she got it, in part, because of his memory of losing his dad in violent fashion.

Shortly after his dad filed the civil lawsuit, members of the now-infamous “TPF” — or Tactical Patrol Force— paid young Lawrence a visit at the Combat Zone parking lot where he was working nights. One of the cops clocked him over the head and two others stuffed him— handcuffed— into the back of a cruiser. The aim was pretty clear: The insular TPF crew needed a chip to horse trade with the elder O’Donnell at the courthouse the next day. Instead, a judge tossed out their trumped-up charge a week later. The message— if it was meant to intimidate the O’Donnells— had the opposite effect. Three years later, their firm scored a huge win and a $250,000 judgment for the Roxbury widow of Mr. Bowden. The TPF, which continued to wrack up brutality complaints in the years after Bowden’s murder, was itself put down by the police commissioner in 1979.

Despite his own assault at the hands of the desperate TPF crew— which included a cop who’d once coached him on a baseball team— O’Donnell insists that many inside the BPD were happy to see the “cowboy” cops who shot Bowden get their come-uppance.

“A lot of the guys that my dad had gone into the department with saw it as a case of young renegade cops watching too much TV,” he says today.

And many of his Dorchester neighbors— despite the prevailing racial animosities that were at an all-time high in mid-to-late 70s in Boston — were largely rooting for the hometown team.

“No one in Dorchester ever said, ‘What are you doing with that civil rights case?’ Even if someone else were doing it, I suspect people were cheering for us, in a much more tribal way, in the good sense of that word,” says O’Donnell. “Everybody in my neighborhood had had run-ins with the police and saw dishonesty of some kind.” Plus, O’Donnell adds, “In Dorchester, personal loyalty is everything. It’s a bigger thing than any individual action.”

Still, in choosing to represent Patricia Bowden against the BPD, Mr. O’Donnell and his family had taken a step that was irreversible. “We all knew it right away. It was very clear at the time. It’s not one of those things that you look back on. All the clarity was there at the time, right in front of us.”

•••

For his part, Lawrence O’Donnell, himself a victim of police brutality, saw that there was historically important story to be told based on the Bowden case. He began documenting cases in which cops had killed mainly black men with impunity in cities around the country. He first wrote about the subject in a 1979 New York Times op-ed piece.

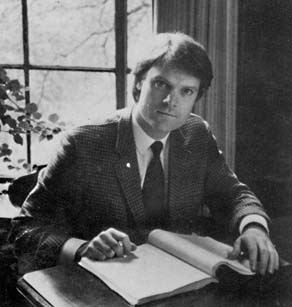

Lawrence O'Donnell, Jr.: This photo appeared on the dusk jacket of "Deadly Force", his 1983 book about the Bowden case. Photo by Frances Buckley O'DonnellIn 1983, the case became his first book: “Deadly Force” — still available locally in the stacks at the Codman Square Library, incidentally – which was subsequently adapted into a movie. It was a pivotal moment in O’Donnell’s life: he found his calling in screenwriting, even though he would defer launching that career for several more years.

Lawrence O'Donnell, Jr.: This photo appeared on the dusk jacket of "Deadly Force", his 1983 book about the Bowden case. Photo by Frances Buckley O'DonnellIn 1983, the case became his first book: “Deadly Force” — still available locally in the stacks at the Codman Square Library, incidentally – which was subsequently adapted into a movie. It was a pivotal moment in O’Donnell’s life: he found his calling in screenwriting, even though he would defer launching that career for several more years.

Despite his utter lack of interest in politics — “I never did anything more than vote for the lesser of two evils,” he says — O’Donnell caught on as an aide and a speechwriter for New York’s US Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan in the mid-1980s. He spent eight years working for the liberal workhorse, eventually topping off the experience as the staff director for the Senate’s Finance Committee.

“I thought I was ruining my writing career,” O’Donnell recalls. Of course, he was also assembling a deep institutional knowledge of the inner workings of Capitol Hill, which led to invitations to serve as a pundit on the emerging cable TV ecosystem. It also powered his writing for Aaron Sorkin’s landmark TV series, “The West Wing”— for which O’Donnell served as a writer and producer. Writing for television, O’Donnell told the Reporter, is “the only occupation I pursued seriously.”

But writing for “The Last Word” was clearly not what he had in mind. His regular gig as an MSNBC pundit— weighing in as a guest on other people’s programs — gave his biting wit and deep understanding of Washington maneuverings a national platform. But it wasn’t something he sought to make his life’s work. Clearly, it still isn’t.

“Every couple of years they’d ask me to host a weekend show. I think the first one I did was cancelled after seven weeks. The next one, I think, lasted six months. I’ve had three weekend shows cancelled that I was the host of without ever putting out a press release saying it was cancelled.”

O’Donnell says he “didn’t seek out” his current 10 o’clock post on MSNBC. But when the pilots for a pair of new television programs he was producing ran aground, his menu of options changed and “I started paying attention” to the network’s pursuit.

Today, O’Donnell writes more words per day for the 10 p.m. show than he has in his life. And yet he says: “I’ve never felt less productive.”

Like any live news show, he says, “The Last Word” “is never even going to be a re-run— it just blows away like leaves.

“I would like to have a crawl that runs throughout the show that says, ‘You are watching an unrehearsed first draft.” It offends me in so many ways that I’m doing it – and I have to force it out of my head. In the world of dramatists that I come from; it’s just so wrong.”

And yet, more often than not in this presidential election season, it has been just right— especially for MSNBC’s bedrock audience of Dems desperate for an authoritiative counter to the more dominant (ratings-wise) FoxNews propagandists. O’Donnell’s solo segment on the show —which he has dubbed “The Re-Write”— is a nightly tour-de-force that takes aim at the right’s whopper du jour. It’s often punctuated with brief video clips offered as evidence, but the sweep and craft of it is all O’Donnell.

“It’s a very peculiar writing exercise,” he explains. “I come from a filmmaking world where you don’t just write it. You physically block out and think through why they will be there. Then you shoot it. To just go out there and do it raw and unrehearsed, and I don’t even know what it looks like... I’m used to being in control.”

O'Donnell takes on Tagg Romney: Many on the right didn't get the gag, much to the anti-anchor's delight.Despite his reservations, O’Donnell was clearly in control on the night of Oct. 18 when his Re-Write segment was an eight-minute take-down of the “Romneymen.” O’Donnell ripped the candidate and his sons and, in fact, Romney’s ancestors, for never— not a one— having served in the armed forces of the United States. The piece culminated with a deliciously subversive bit targeting the candidate’s eldest son, Taggart, who had made some rather clumsy remarks that day about occasionally wanting to “take a swing” at the president for calling his dad a liar.

O'Donnell takes on Tagg Romney: Many on the right didn't get the gag, much to the anti-anchor's delight.Despite his reservations, O’Donnell was clearly in control on the night of Oct. 18 when his Re-Write segment was an eight-minute take-down of the “Romneymen.” O’Donnell ripped the candidate and his sons and, in fact, Romney’s ancestors, for never— not a one— having served in the armed forces of the United States. The piece culminated with a deliciously subversive bit targeting the candidate’s eldest son, Taggart, who had made some rather clumsy remarks that day about occasionally wanting to “take a swing” at the president for calling his dad a liar.

O’Donnell pounced on the opening:

“When I hear you talk about taking a swing and taking punches, why do I get the feeling you have never actually taken a punch, or thrown a punch. I didn’t have that luxury in the part of Boston I grew up in. But in your rich, suburban, Boston life, with your father filling a $100 million trust fund for you. I don’t know, I just get the feeling that things were kind of different for you.”

In the final few minutes, O’Donnell dropped his non-regional diction and went all native tongue on Taggart. He pushed away from his desk, strolled to the camera and with all the manufactured bravado he could muster, he started to channel Jimmy Cagney with a dash of Mark Wahlberg in “The Departed.”

“You’re mad at President Obama for callin’ your fathah a liah? Let’s get something straight: He didn’t call your fathah a liah. I did. I’ve been sayin’ all year that your fathah is a liah. You wanna take a swing at someone for calling your old man a liah? ... He closed: "Go ahead, Taggart. Take your best shot.”

Predictably, most right-wing bloggers — and even many on the left— took O’Donnell’s challenge as a legit offer to throw-down in fisticuffs. Several, evidently thinking that all Boston Irishmen must live on the “Good Will Hunting” set, jabbed at his faux “Southie” roots.

O’Donnell still gets a kick out of the fact that anyone took it seriously.

“I said, ‘Take a swing at me.’ I never said what I would do. Last time anyone took a swing at me, it was a Boston cop and I had the good sense not to swing back. I sued him and won.

“All of this is within a world that’s completely ridiculous in the first place. The trouble with American TV now is that it needs everything to be very plainly labeled.

“Long term viewers of mine knew it was a joke. The Huffington Post was careful to say I didn’t challenge him to a fight. I would never want to complete the joke.

“When in doubt, I will err on side of open interpretation. I don’t do it without knowing the risks. I was amused with the variable outcomes. There’s also a certain, ‘Aha, I get the sense this person is not content with being an anchorman.’”

•••

In a telling passage from his book— published in a different era in human history (the dawn of the Reagan administration), Lawrence O’Donnell wrote about a strange thing that happened after he was beaten by the police in that Combat Zone parking lot: For some reason, he let it go. Sure, he sued the cops who bashed him over the head, but in a small city like Boston, he’d run into the same fellows again and again— outside courthouses, restaurants, the corner store. Like them, he learned to let it go.

“I can’t explain what happened to all that anger we aimed at each other in 1975,” he wrote. "It’s a Dorchester thing, maybe an Irish thing, this ebbing of ill will— but then, so is holding lifetime grudges, something I’ve been doing with a couple of people who’ve never even hit me. I’ve seen best friends slug it out to the point of black eyes, chipped teeth, and broken jaws. As often as not, after some months of awkwardly avoiding each other, they’re suddenly friends again. There’s never an apology, just the unstated realization that what happened was stupid and no lasting harm was done.”

It’s the kind of sentiment that was in ready supply, if only fleetingly, as a tense election night turned into the day after. Will Lawrence O’Donnell and his colleagues on MSNBC bring a similar message of “get over it and move on” to their audience in the coming days? Tune in to find out.

Topics: