July 15, 2020

Democracy wilts with low voter turnouts. When turnout is low, vested interests are typically the winners, which creates an imbalance in governance. Last year’s city council elections produced a turnout of 11.17 percent in the preliminary election and 16.5 percent in the final election, which meant that of the 402,536 people in Boston who were registered to vote at the time of the election, only 44,972 cast ballots in September, and only 67,011 voted in November. Put another way, in September, 357,564 registered Boston voters didn’t vote , and in November, 335,525 declined to participate in the election.

The main story out of that campaign was the close race between Julia Mejia and Alejandra St. Guillen for the fourth and final seat in the at-large (citywide) balloting, which was ultimately decided by one vote: 22,492 to 22,491. The scandal of the election is that while one vote determined who won and who lost, 335,525 registered voters decided not to cast a vote.

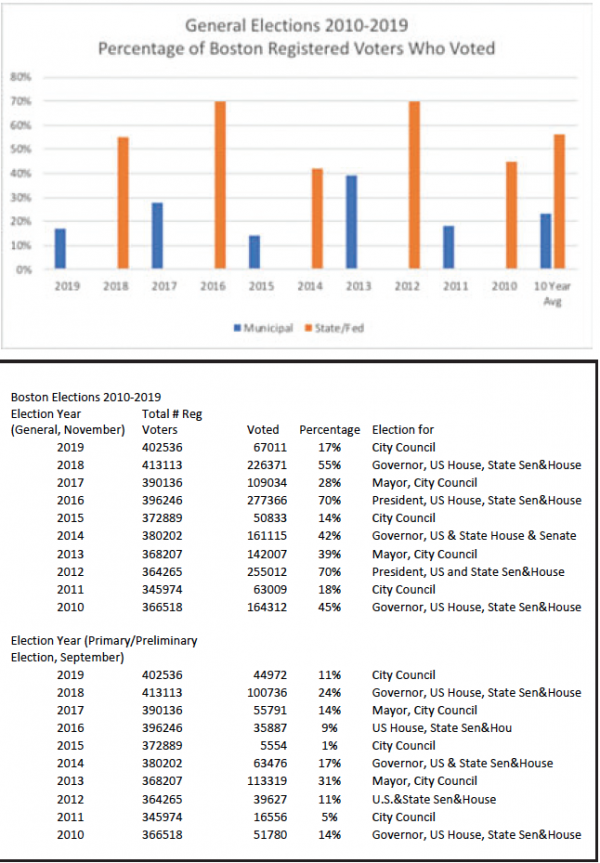

I looked at the last 10 years of voting in Boston and noted that the percentage of voters who went to the polls depended on which offices are on the ballot. While that may be obvious to most, a deeper analysis shows a way to increase turnout for municipal elections.

The data show that the November elections held in even-numbered years, when state and federal office holders are elected, averaged 56.4 percent turnout of registered voters, whereas odd-numbered year balloting, when only municipal offices are elected, averaged exactly half that, at 23.2 percent (see adjacent charts, with information from boston.gov).

Which leads me to the following conclusion: With the average number of registered voters in election years between 2010 and 2019 at 380,008, eliminating the odd-number year balloting and putting election of all offices on the ballot in even-number years would increase the potential turnout for city office elections by 88,162 on average, doubling the actual average turnouts in the last decade.

Significantly, having elections only in even years would eliminate the costs of the preliminary and general elections in odd-numbered years, estimated at upwards of $1.5million.

Having our municipal elections held in odd-numbered years dates back almost 100 years to when Boston’s Charter was amended to read: “Beginning in the year nineteen hundred and twenty- five, the municipal election in said city shall take place biennially in every odd numbered year on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November.” According to its introduction, the Charter is “a series of State statutes and not a single code.” It has been amended numerous times, as recently as 1993. So, it could be changed to determine that “municipal elections shall take place on the date of state elections.”

Coordination with state elections would be necessary. The Secretary of State’s Election Office notes that while all elections are administered by the cities and towns in which they are held, the state has responsibility for state elections (e.g., determining and printing up the ballots and overseeing the voting), and municipal election management is the responsibility of the city. So changing state election law to mandate that municipal offices be voted on at the same time and same ballot as state offices would require changes in the state election laws. But the State Election Office also notes that if there were separate ballots and systems for state and municipal offices, it would be less of a problem to have all offices elected on the same day, instead of separate years. Lastly, it would require a onetime fix: An additional year would be added to the current terms of the mayor and the city councillors so that future elections would be in sync.

Some could make the case that separating state election bureaucratic oversight from city election bureaucratic oversight was, and is, a good enough reason for why the election process is set up the way it is. However, with many changes happening, or likely to happen, to the election system, this is the time to take on the timing of the balloting. A change might even result in more competitive city elections.

Given the likely doubling of the number of Boston voters who would get a ballot for city council and mayoral races if municipal elections were held on the same date as state balloting, –and given the money to be saved by eliminating unnecessary elections – I don’t see a good reason to continue holding elections in odd-numbered years.

Bill Walczak of Dorchester is the co-founder of the Codman Square Health Center and was a candidate for Mayor of Boston in 2013. His column appears weekly in the Reporter.