February 7, 2019

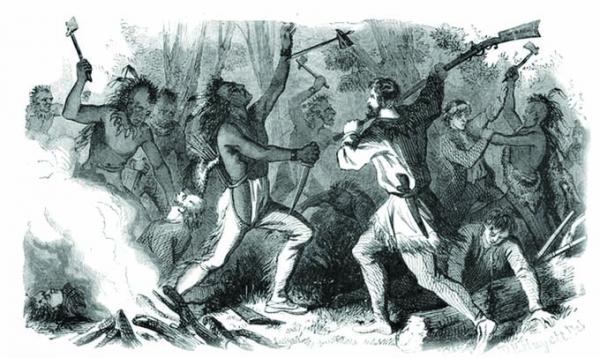

The fight at Bloody Brook. Courtesy New York Public Library

By Ed Quill

Following is the last in a series of excerpts taken from the recently published book by Mr. Quill – “When Last the Glorious Light; Lay of the Massachuset’ – a story centered on the fate of the Native American tribe called the Massachuset, from which the state took its name.

Because a genocidal war was named for him, tradition has blamed the 17th Century war on King Philip (Metacom) and, although he was preparing to start one, he wasn’t ready when that fierce and fiery rebellion broke out. There is still dispute over who fired the first shot. Moreover, the Wampanoag sachem was obviously a reluctant participant throughout.

Nevertheless, there’s no question his angry young warriors were frustrated and furious over repeated humiliations, debilitating land-takings, and injustices perceived over English-dominated court proceedings, including the hanging of fellow tribesmen thought to be innocent. At some point, there was going to be a war.

Thus, English communities were attacked, sacked and, in some towns, burned to the ground. Inhabitants – many innocent women, children and old men – were slaughtered, some in King Philip’s name, although he may not have had anything to do with these inhuman acts. Some natives were unquestionably savage in their outrage. King Philip himself never called for the brutal treatment of innocent citizenry. He himself treated captives honorably.

On the other hand, the English way of war in the 17th Century was the Cromwellian way – total destruction of whole villages with little if any regard to women, children, or old men who had taken up no arms in battle; they simply were allowed no truce or chance at parley for peace. The English way was to burn native campsites before innocents could be moved out of harm’s way. … and the newcomers had a powerful personage in charge of a genocidal war: Josiah Winslow.

So, before we blame King Philip as the great villain for starting and steering the great war that carried his name and that shattered the once all-powerful Massachuset tribe, we might want to review the activities that the Plymouth Colony Governor and allied Commander-in-Chief engaged in during this period:

• Winslow was named Commander-in-Chief of the combined Massachusetts Bay-Plymouth-Connecticut armed forces in the war and used slavery as a weapon. In one instance, when several hundred natives had been promised amnesty, they surrendered; but when they came before Winslow’s Council of War, they were convicted and shipped to Spanish Cadiz as slaves. Untold hundreds were “devoted into servitude” under Winslow’s rule.

• As commander at the Great Swamp Fight at South Kingston, Rhode Island, in a bitter February 1676, he refused amnesty, refused to parley, and ordered the attack in a massacre of 700 to 1,000 natives, mostly women and children who burned to death in their village encampment. Before this act, he told his men that, if they were victorious, they would each receive a generous reward of land. So, this wasn’t a holy war to save Christianity from the pagans, as propagandized. It was another big land grab.

• He led New Plymouth’s Council of War in ordering the forced removal of all Massachuset men, women and children to incarceration on cold, unsheltered and desolate Clark’s Island in Plymouth Harbor, where an estimated half of possibly 500 or more are certain to have perished (there are no records) from starvation, disease, and the elements of that harsh winter.

•••

In the year and a quarter of King Philip’s War, the natives attacked two-thirds of the English towns in Massachusetts Bay colony, destroying six of them. Eleven others were either burned down or else sustained serious damage. The natives had killed or captured one in every ten or eleven adult English males – an estimated 600 men killed of the 5,000 of military age. On the settlers’ side, dozens of women and children were killed or injured – mostly as a result of village burnings. Native women and children were killed or injured in campsite burnings. Some 1,200 English houses were burned and 8,000 head of cattle killed.

Thousands of Wampanoag, Nipmuc and Pocumtuck, as well as their later allies, the Narragansett – along with Mohegan, Pequot, and Christianized natives, mostly Massachuset and Pawtucket – died too, an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 in all. Untold wigwams were destroyed with all of their furnishings.

The United Colonies claimed that the war had cost them between 100,000 and 150,000 English pounds. …

We have little idea what it cost the natives in financial terms, except that, in the long run, it cost them much more than the Pilgrims and Puritans. With less land and, with their cornfields unplanted, it left them in dire consequences. And it left them under total English subjugation, with greater restrictions of movement, habitation, and legal rights.

At least one historian wrote that “no tribe had been annihilated in the war.” If not annihilated, it must be said that the war most assuredly led to the near elimination of the Massachuset people and possibly the Pawtucket, and that each to this day are not recognized by the United States government as an authentically organized tribe.

•••

After King Philip’s War, the English began to purchase property deeds from the natives at Punkapoag. Captain Ebenezer Woodward made a survey and plan of the original Punkapoag plantation in 1725, after an order was given to do so by the General Court. But by 1756, Robert Spurr, who was guardian of the natives, found himself “very much embarrassed,” or unable, to determine the boundaries between the lands of the English and the natives. It was asserted that neither the natives nor anybody else had a plot plan, and that no trace of any field notes could be found.

As a result, Spurr asked the General Court to order all English property owners in Canton abutting native land to produce their deeds, as well as pay their proportion of the fee for surveying the native lands adjoining them. The request was granted. Both sides paid for the plan, which was finished in 1760. It turned out that by this time, some 100 years after the natives had been granted 6,000 acres, they now had land amounting to 710 and three-quarter acres.2 The native-owned land at Punkapoag “would disappear entirely between 1760 and 1780,” wrote historian Daniel R. Mandell. Some five surviving natives were living there at the time, according to Mandell, who wrote: “. . . Punkapoag land was sold to pay debts arising from basic needs, and the Indians . . . relied on fishing and gathering economies and avoided extensive English-style agriculture. Even in 1768, the five Punkapoag survivors noted their ‘dispirs’d scattered manner of living.’”

•••

The Massachuset, among “the People of the First Light,” aren’t extinct – they live still, as individual persons, many active in Native American affairs. It would be quite difficult, however, for them to become a federally recognized tribe under current legal conditions, unless the criteria, as established for formal recognition by the US Congress in 1978, were changed. As of now, as historian Karen H. Dacey has put it succinctly:

• A tribe must be recognized from historical time to the present as aboriginal.

• A substantial number of tribal people must live in the same area and be viewed as a separate community from the population around them.

• Modern tribal members must be descended from the Native people who originally inhabited the locale.

• The tribe must have maintained a distinct political influence from earliest times and have a tribal government in place today.

• The tribe must not be part of any other tribal authority.

• A tribe must have a written constitution.

• It must have a set procedure for determining a tribal membership and maintain a verifiable roll of all “bona fide” members.

It should be noted that the federal recognition process has become increasingly controversial because, for one thing, some recognized tribes don’t want others attaining recognition – the reason being the increasingly narrow slices of the federal funding “pie.”

The Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs recognizes the following tribes in the Commonwealth, representing some Wampanoag and Nipmuc peoples:

Chappaquiddick Wampanoag; Chaubunnagungamaug Nipmuc (Dudley); Hassanamisco Nipmuc (Grafton); Herring Pond Wampanoag; Pocasset Wampanoag; Seneonke Wampanog

According to the Indian Affairs Commission, two groups – the Natick Massachusett and the Ponkapoag Massachuset – are native people whose heritage and histories are known and whose state recognitions were pending at the time of this book’s publication.

•••

The Massachuset – along with the Pokanoket and Pawtucket – gave sustenance to the early Pilgrims and Puritans. They helped the early settlers when asked. They fought them only when provoked. The Massachuset are known to have rebelled in a few rare cases. They took revenge against the violation of Chickataubut’s mother’s grave and when their food was stolen at Wessagusset. They shared their land and its abundance. And, with rare exception, their kindness and hospitality were not well received. What they got in return was arrogance, oppression, cruel treatment, and segregation.

The Massachuset people, the people of the Dawnland, aren’t extinct, however – they live still, not as a federally-recognized tribe perhaps, but like the grand sachem and his squaw at their seasonal villages, their powwaw, pniece and sannop, they are scattered now like the severed leaves in a southwest autumn wind. …

But the old campsites, the old lodges, wetus and wigwams atop the Blue Hills and below in the valleys – at the Neponset falls and at Shawmut (Boston), at the coastal Moswetuset Hummock at Squantum (Quincy) and Wessagusset, at Natick, Punkapoag, at Mattakeesett (Pembroke/Hanson), even Titicut – are gone now, carried into the mists of remorse.

At the range of hills – from which the tribe got its name, the Massachuset, or as the natives prefer to call themselves, the Massachuseuk – many names remain: Chickatawbut Hill and the nearby Chickatawbut Overlook; and Kitchamaken Hill, only half the height of Great Blue, and Wampatuck Hill, with nearby pathways called Squamaug and Sassamon – all within today’s Blue Hills Reservation.

Above all and highest of all, granite-encrusted Great Blue, in foggy mist or sparkling sun, stands in solemn salute to the oral tradition and remembrance of this proud and noble people.

End of series

Copyright c 2018 Ed Quill, by Silver Lake Press, Inc.

This book can be purchased through PayPal on the website quillcloud.net.