October 18, 2018

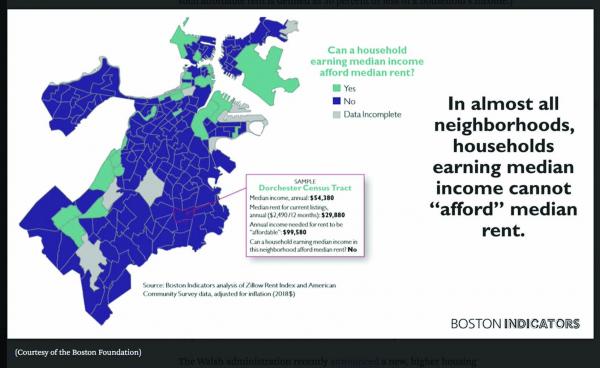

A graphic courtesy of the Boston Foundation displays rent affordability, or lack thereof, in Dorchester.

A growing Boston added tens of thousands of households from 1990 to 2014, according to a recently released Boston Foundation study, while at the same time, the report’s authors say, the city’s middle class was shrinking overall.

In that time frame, the study states, the number of high-income households in Boston jumped by 43,000 and the number of low-income households increased by 30,000 while the tally of households at the middle of the income distribution fell by 15,000.

The foundation’s figures mirror findings on the national level that show a decline in the household share of middle-class Americans.

The report cites the growth in the share of high-income households as a reflection of Boston’s addition of higher-wage jobs in health care and informational technology sectors; it also notes that high housing costs play a key role, as well, in who lives where in a growing housing market.

“As demand to live in Boston dramatically outpaces the production of new housing, higher-income households are the only ones equipped to stay and pay market rates,” the analysis states.

The Boston Foundation has advocated for an increase in housing production in the area as a way to moderate housing costs. A new coalition of 15 municipal leaders that includes Boston Mayor Martin Walsh just last week called for the creation of 185,000 new housing units by 2030.

The report — titled “Boston’s Booming ... But For Whom?” — collected data from a number of sources on a variety of economic indicators for the city and region, including income inequality, poverty, economic mobility and home ownership.

As the Boston Foundation’s president and CEO, Paul Grogan, writes in introducing the study,”there is some encouraging news” in the analysis, such as Boston’s overall prosperity and relative strength in economic mobility, compared with peer cities.

Nevertheless, the report focuses on the area’s inequities along lines of race and class.

Boston does well, compared to other cities, for women and people of color. That comparison point is critical. Although Boston ranks first for black mobility relative to the 99 other largest commuting zones in the US, within the city itself black men rank lowest in economic mobility across race and gender groups.

“Finding ways to better leverage our economic boom for the benefit of all residents and all neighborhoods has become the central challenge of our time,” the authors conclude.

The analysis adds another sobering statistic to Boston’s issues with housing affordability: In just 20 of the city’s 170 census tracts, households earning the median income can comfortably afford the area’s median rent. (In this report, such affordable rent is defined as 30 percent or less of a household’s income.)

“It’s striking,” the analysis states, “that wide swaths of several neighborhoods that were once thought of as affordable actually are not. ... In 2018, every single census tract in Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan is unaffordable to households earning median incomes.”

For all of Boston, median monthly rent is $2,613, per the report — a total that’s 51 percent of median household income in the city.

Families who need to spend more than 30 percent of their income to live in their neighborhoods, the report notes, make critical adjustments, like living in less desirable units, doubling up with other friends or family, and going into debt.

Suffolk County has been more affordable for extremely low-income residents than comparable counties, the report states, but that is still not enough to meet demand. The Foundation cited a report that found Boston has made 61 affordable units available for every 100 “extremely low-income” households in Suffolk County. The US average is to make only 45 units available per 100 such households.

The Walsh administration recently announced a new, higher housing production target, saying it is outpacing its original goal, which was announced in 2014.

The focus of the housing plan, Walsh told reporters two weeks ago, is to “make sure that people can stay in the city of Boston.”

The city has said it expects to have about 100,000 more residents by 2030.

This article was originally published by WBUR 90.9FM, Boston’s NPR News Station on Oct. 10. The Reporter and WBUR have a partnership in which the two news organizations share content and resources. The Reporter’s news editor, Jennifer Smith, contributed to this version of the story.