October 8, 2014

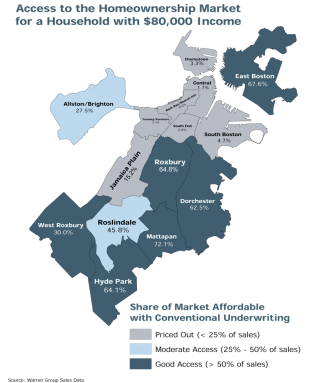

City Housing Report 2014-2030: A graphic from the city report characterizes "access to the Homeownership Market" by neighborhood. Image courtesy City of BostonThe Walsh administration released its first housing plan this week. The 140-page document is titled “Housing a Changing City: Boston 2030” and lays out the major challenges and goals for meeting the demand for new housing for a population that is on the rise. The plan anticipates that the city’s population will surge past the 709,000 mark by 2030 — a growth from today of some 91,000 people.

City Housing Report 2014-2030: A graphic from the city report characterizes "access to the Homeownership Market" by neighborhood. Image courtesy City of BostonThe Walsh administration released its first housing plan this week. The 140-page document is titled “Housing a Changing City: Boston 2030” and lays out the major challenges and goals for meeting the demand for new housing for a population that is on the rise. The plan anticipates that the city’s population will surge past the 709,000 mark by 2030 — a growth from today of some 91,000 people.

The report notes that the last time Boston was home to 700,000-plus people was in the 1950s. Back then, large families often lived in a single unit — like the classic Dorchester three-decker experience. In today’s Boston, this report notes, “fewer people inhabit each unit of housing, making our current housing stock insufficient to accommodate this growth.”

Insufficient is putting it mildly. Even in Dorchester, which is categorized in this report as one of the city neighborhoods with “good access” to middle income housing, it is becoming increasingly difficult for people to find affordable homes or rental units.

The report is candid in saying that “given the constraints of space, the high cost of land, declining federal funding, and a finite amount of City dollars available, we must acknowledge that the City cannot build its way out of this problem.” But, build we must. The Walsh plan pledges to produce 53,000 new units of housing between now and 2030 – a growth of 20 percent in terms of the number of households.

They’ll reach this number, according to this document, through a series of initiatives, including:

• Encouraging more on-campus housing (dorms) for the city’s 152,000 students — of whom 36,000 currently live in off-campus units. The plan calls for 16,000 new dorm units, reducing the number of off-campus students by 50 percent.

• Improving the city’s permitting process to “unlock greater housing production”— with a new, universal online application portal to allow developers to track status of permits. The importance of this is emphasized repeatedly in the report, which notes that 73 percent of all private housing starts in Dorchester between 2011-2014 have been small projects — characterized as 1-9 units. These are described as “a critical part of the city’s efforts to promote middle-class housing production in lower-priced neighborhoods.”

• Critically, the Walsh team plans to “allow for more as-of-right support for housing and re-zoning around transit hubs”— a pledge that bears watching as current plans for new units in Savin Hill and Ashmont are weighed at the community level.

• Increasing the annual city budget for affordable housing starts from roughly $31 million to $52 million. The document anticipates that one way to do this will be to “increase the cash-out obligation from developers, especially in high-end developments.”

• Reducing the number of foreclosures, which has already dropped precipitously since the crash of ’09, to less than 20 per year and encouraging existing “bank-owned” properties, which today number around 200, to be cycled back into the market.

The report also details some interesting facts about the current housing situation in the city — and specifically here in Dorchester, which has the largest share of total households in Boston with 31,098. Of those, 18 percent get some kind of Boston Housing Authority assistance — also the largest amount in the city. The report notes that the average monthly rent in 2013 in Dorchester was $1,600— a sum shared with neighborhoods like Roslindale, West Roxbury, and Roxbury. That’s compared with average rents of $1,900 in Allston-Brighton and $2,300 in Fenway-Kenmore.

City Housing Report— 2014-2030The Housing Task Force that has been told to put this plan into action by Mayor Walsh will have its hands full. The report serves as an excellent overview of the current landscape and gives a much-needed road map for moving forward. The report concedes that the city “does not have good systems” in place to offer the transparency and efficiencies that this plan envisions.

City Housing Report— 2014-2030The Housing Task Force that has been told to put this plan into action by Mayor Walsh will have its hands full. The report serves as an excellent overview of the current landscape and gives a much-needed road map for moving forward. The report concedes that the city “does not have good systems” in place to offer the transparency and efficiencies that this plan envisions.

But proper execution of this plan will necessitate immediate progressive reform within city government, particularly in permitting and zoning practices. These will not come without a share of neighborhood pushback on individual projects. The Walsh administration must send a clear message in the near term that they won’t let parochial objections stand in the way of the city’s overall goals.

Topics: