January 8, 2014

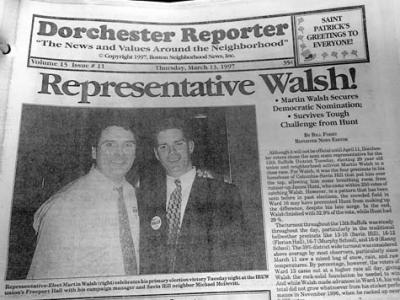

We Knew Him When: The cover of the March 13, 1997 Reporter carried news of Martin J. Walsh's special election victory. Shown with him is campaign manager Michael McDevitt. Photo by Bill Forry

We Knew Him When: The cover of the March 13, 1997 Reporter carried news of Martin J. Walsh's special election victory. Shown with him is campaign manager Michael McDevitt. Photo by Bill Forry

On Monday, the city and the region got its first extended glimpse of the political leader whom we’ve come to know, simply, as Marty. It was a good first impression and a reminder of why he won last fall: People want to like him.

They also want him to get better— to achieve more than even they thought he could. They still do. Like every one of us, he’s a work in progress. And that has been the case with him since Day One of his move into politics.

For folks from Dorchester, he is now the vessel of their own aspirations: the kid from the three-decker on Taft Street who has beaten cancer, a drive-by bullet blast, and “the disease” to grasp his city’s ultimate brass ring. Marty has become living, breathing proof that we can tame our own demons and even harness them for the purposes of a greater good— like ministering to an emerging generation of Bostonians whose futures are similarly imperiled by bullets and booze.

The confident, poised, and at times eloquent Marty Walsh who breezed through his Conte Forum address on Monday morning is a far cry from the hesitant, harried candidate I first encountered on a King Street sidewalk in the winter of 1997. He had come to Pope’s Hill—then foreign turf for the Savin Hill upstart – to give his first press conference in the special election to succeed Jim Brett in the 13th Suffolk rep’s seat. Walsh was nervous and edgy. His remarks were unremarkable – read from a 12-page “public safety” platform pamphlet — but they weren’t what was important then. He was there to fly the flag in Neponset’s Ward 16, to eat into his rivals’ base, and to project the strength of a candidate who had managed to maneuver himself into an enviable spot. Two weeks before, his principal rival from Savin Hill— Rosemary Powers— had dropped out of the contest and thrown her support to him, giving Walsh a clear strategic advantage in the upcoming March special election.

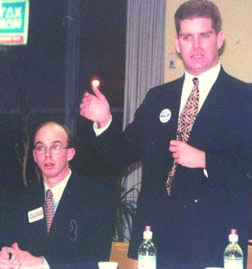

Candidate Martin J. Walsh in 1997: In a debate during the special election for 13th Suffolk state representative. Next to Walsh is candidate Jim Hunt III. Photo by Bill ForryThere were other very good candidates in the race: Charles Tevnan, a lawyer from the Ashmont-Adams area; Jim Hunt III, then a law student and State House aide from a respected Neponset family; and a thoughtful, but unknown assistant DA named Martha Coakley. All of them— and two other candidates— lived in the same Ward 16 neighborhood. Hunt emerged as Walsh’s chief rival, but the Ward 16 folks chewed each other up on election day — and Marty took home 32 percent to Hunt’s 29. His Savin Hill dominance, union support, and fundraising prowess — all orchestrated by a top-notch campaign manager, Mike McDevitt (shown on the victory cover of the March 13, 1997, Reporter), consultant Ray Mariano, and Savin Hill political king-maker Danny Ryan.

Candidate Martin J. Walsh in 1997: In a debate during the special election for 13th Suffolk state representative. Next to Walsh is candidate Jim Hunt III. Photo by Bill ForryThere were other very good candidates in the race: Charles Tevnan, a lawyer from the Ashmont-Adams area; Jim Hunt III, then a law student and State House aide from a respected Neponset family; and a thoughtful, but unknown assistant DA named Martha Coakley. All of them— and two other candidates— lived in the same Ward 16 neighborhood. Hunt emerged as Walsh’s chief rival, but the Ward 16 folks chewed each other up on election day — and Marty took home 32 percent to Hunt’s 29. His Savin Hill dominance, union support, and fundraising prowess — all orchestrated by a top-notch campaign manager, Mike McDevitt (shown on the victory cover of the March 13, 1997, Reporter), consultant Ray Mariano, and Savin Hill political king-maker Danny Ryan.

The 29 year-old Walsh was eager to make friends outside of his comfort zone. Unshackled from the tension of a hard-fought, six-way race, his natural, good-natured style began to show itself more. He threw himself into the work of being a lawmaker, but more importantly, as a go-to person for people with problems.

“Marty chose people over power and by empowering other people he empowered himself,” says Danny Ryan, his mentor and earliest political conscience. “He’s addicted to helping people.”

Under Tom Finneran, who was midway through his tenure as House Speaker when Walsh arrived, he was able to deliver big ticket items to his district, including long-delayed funding to build out the 72-acre Pope John Paul II Park in Neponset. Walsh played a supporting, but important, role in compelling the MBTA to pay for major upgrades to Dorchester’s four Red Line stations. And he put the heat — and a heaping dose of Irish guilt— on the old MDC to get Morrissey Boulevard’s crumbling Beades drawbridge (shown below) replaced, dramatically telling the Reporter in 1999: "I don't want my parents driving over the bridge when it collapses.”

As disciplined as he was in his personal life, Rep. Walsh sometimes seemed to flail about politically. In Finneran’s wake, he backed the wrong horse in two House leadership fights. In January 2002, he went public with his interest in becoming Suffolk County Registrar of Deeds — hardly a job coveted by a politician with higher aspirations. A week later, he pulled back from the brink— and despite being offered the job by Secretary of State William Galvin— opted to stay on course in the House.

"I've sat in the House chamber looking around and this job is the best job I've ever had and for as long as the people of Dorchester will have me, or until I decide to move on, this will be the best job for me," he told the Reporter.

Perhaps Walsh’s most notable local dust-up came in 2001 when Stephen Lynch left the State Senate for the US Congress. The contours of the First Suffolk Senate seat had recently been re-drawn to include almost all of Dorchester along with South Boston and Mattapan— a dynamic that eventually helped my wife —Linda Dorcena Forry — win the seat in March 2013. But in November 2001, rather than entertain the idea of a Dorchester candidacy, Walsh immediately threw his full support to South Boston’s Jack Hart — a move that cemented a political alliance with Lynch and Hart that was already strong and one that would later kick in to help Walsh dominate the votes in last year’s mayoral election.

At the time, this reporter and others were sharply critical of Walsh’s endorsement of Hart. It seemed like a rash and selfish decision— one that seemed to dismiss the notion of a Dorchester candidacy by either Walsh, Maureen Feeney, or a crossover candidate of color, including former Rep. Charlotte Richie or her successor, Marie St. Fleur.

But Walsh was unmoved by the critique.

In a letter to the editor, he defended his decision and criticized the Reporter (me) for “incorrectly inform[ing] readers that my support of Representative Jack Hart in the voting to elect a new senator from the First Suffolk District would come at the expense of Dorchester residents…. Its editors were reckless to lay the foundation for a wedge driven between the two communities who will occupy the new Senate district.” Hart cruised to victory unopposed in the special election that followed.

Despite our disagreements— and there were other, less public instances – Marty Walsh never shut off the lines of communication or sought to exact revenge on this newspaper. He can get angry— and he’ll let you know he is. But he has always come back to earth and acted professionally. He seemed grudgingly to accept— and expect— our scrutiny, and the criticism that would follow. He knew he would get a fair shot at getting his side out. It’s safe to assume that as he takes on his newest challenge, minor tussles with watchdog reporters will no doubt be counted as an important part of his political education.

More often than not, the Reporter tracked Walsh’s career with routine reports about bills filed and campaigns won. He showed guts on many occasions and defied expectations. He defied an unhappy civic association crowd that wanted to block the Pine Street Inn from converting a dilapidated six-family house on Pleasant Street into transitional housing for the homeless. In the fight over building dorms on the UMass Boston campus, he defied his fellow union chieftains and stood alongside his Savin Hill neighbors in opposing dorms. And he would tell anyone who cared to listen— well before the Goodridge decision— that he’d happily vote to give gay men and women the right to marry.

"If you want to label me a liberal because I'm supportive of people who are trying to get sober and trying to recover, and trying to stop infectious diseases, they can label me as a liberal all day if they want," Walsh told former Reporter editor Jim O’Sullivan, in a 2004 profile. "Because I'm a white Irish Catholic, people will assume that I'm gonna be a conservative, and I think that's unfair because people don't get an opportunity to talk to me and ask me my positions on the issues, or talk about issues. I think it's kind of an unfair label."

Mayor Walsh: The new mayor waved to the Conte Forum crowd on Monday, Jan. 6, 2014. Photo by Chris LovettWalsh’s best quality— the one that makes him so likeable — could be his greatest potential weakness in the mayor’s job: He’s a pleaser. He wants to leave everyone smiling. He seeks to defuse confrontation and focus on the things people have in common. This instinct makes him eminently electable, but it harbors the risk that candidate Connolly sought to define: That Walsh won’t be tough enough to say no when it counts, if it means losing a friend.

Mayor Walsh: The new mayor waved to the Conte Forum crowd on Monday, Jan. 6, 2014. Photo by Chris LovettWalsh’s best quality— the one that makes him so likeable — could be his greatest potential weakness in the mayor’s job: He’s a pleaser. He wants to leave everyone smiling. He seeks to defuse confrontation and focus on the things people have in common. This instinct makes him eminently electable, but it harbors the risk that candidate Connolly sought to define: That Walsh won’t be tough enough to say no when it counts, if it means losing a friend.

It says here that Walsh has it in him.

Topics: