January 20, 2011

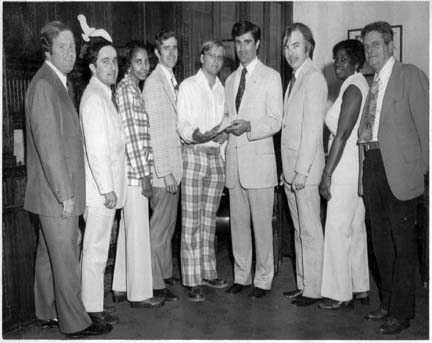

Walczak speaks in 1979. At left, Mayor Kevin White; at right state Rep. W. Paul White. Photo: CSHC.

Walczak speaks in 1979. At left, Mayor Kevin White; at right state Rep. W. Paul White. Photo: CSHC.

Give Marge Muldoon her share of the credit.

As the president of the Codman Square Civic Association, she made a fateful decision one night in December 1974 during a meeting in the basement of “the white church” — the landmark Second Church of Dorchester. She gave Bill Walczak an assignment that changed his life and, eventually, the course of history in our neighborhood.

Marge Muldoon told Bill Walczak to go for broke on his dream of locating a health center in the square. And he believed her.

At the time, Codman Square was experiencing just about every form of urban decay imaginable. Arsonists fueled nightly blazes that pock-marked the side streets west of Washington as the outfall from the notorious B-BURG housing program marched across the neighborhood. Gangs of young men — black and white— battled with knives, guns, and fists for control of parks, basketball courts, and street corners. The Boston Globe proclaimed the area Boston’s Badlands and the faded photos and news clips suggest that the headlines were far from hyperbole.

Marge Muldoon and her mostly white civic group first convened days after the 1973 slaying of 21-year-old Robert White, Jr., who was ambushed — along with a group of friends— behind the old Dorchester YMCA near Roberts Field. White’s murder— at the hands of a gang of black assailants— marked a new boiling point in Boston’s festering race cauldron. And this was the year before a federal school busing plan sparked the still-infamous clashes in South Boston, Roxbury, and Charlestown.

Into this environment marched Bill Walczak, the son of union factory workers from Iselin, New Jersey, a blue-collar community at the crossroads of northern Jersey’s then-pulsating industrial pipeline. Unlike most of his neighbors, young Bill attended a Jesuit boys school and won a scholarship to Boston University, becoming the first in his family to go to college.

In 1974, he was a long-haired, 20-year-old upstart who was viewed as a “punk” by some longtime residents. He had dropped out of BU to help Cesar Chavez fight for migrant workers’ rights in Colorado. Joining him there was a like-minded Dorchester girl, Linda Johnson, whom he had met while hitchhiking home from a Cape Cod weekend. Soon after, she invited Bill and his buddies to help her move into a Lyndhurst Street apartment and then to a Halloween party. It was a short trip from the party to love and marriage in St. Gregory’s Church in 1973; they were both 18.

The newlyweds— whose first date was a trip to a counter-inaugural to Richard Nixon’s in 1972— moved into an unheated apartment in a three-decker on Edwin Street and did what came naturally: They got involved, and busily so. Linda was attending UMass-Boston and Bill had landed a job working as a spray painter at the Raytheon plant in Waltham.

But, they couldn’t shake the activist bug. Inspired by Chavez and the Catholic Workers Movement, the Walczaks were deeply moved by the injustices and civil rights abuses unfolding all around them.

Down Talbot Avenue from Codman Square, Charlie O’Hara was raising his own family on Ashmont Hill when he noticed Walczak at one of the “white church” meetings. The young man was hard to miss.

“Bill was a 20 year-old radical with long blonde hair hanging down over his shoulders,” O’Hara recalls. “Everyone knew him because he had an awful lot to say.”

During one meeting, as homeowners called out for more police to crack down on vandals and muggers, some— like O’Hara— wanted to talk about a related problem: The rapid flight of family doctors.

“Medical care in those days were family doctors, who usually lived in the second-floor of a Victorian house and had an office or exam room on the first floor. There were three of them at one point on Ashmont Street between Peabody Square and Washington Street. But they were getting better deals to get office space elsewhere in Quincy and at Carney Hospital and there was a dearth of doctors in this area. All these guys left. So people were saying, ‘My doctor’s gone and nobody wants to come in here.’ People were literally packing up and leaving because, honestly, Codman Square was a nasty place back then.

“Bill got up and said, ‘Let’s start a health center!” O’Hara remembers.

Two old-timers in the front row chuckled, said O’Hara. One turned to the other and cracked, “Jesus Christ, another one of his crazy ideas.”

“The president [Muldoon] had a way of dealing with people like Bill,” O’Hara says. “Anything she didn’t think would fly, she’d put that person in charge. So, she entertained a motion to elect Bill to head the health center committee. He had no support, nothing. Bill got up and said anyone who wants to volunteer to be on the health committee, stay around after the meeting. I kind of felt bad for him.”

As O’Hara puts it today, “Too bad we don’t have more of those crazy ideas. And it really was, but he persisted and he was a pit bull. We spent the first couple of years trying to calm him down.”

Walczak and O’Hara were joined by a small but tenacious band of residents who mostly bought into the health center idea. One was Seaborn Scott, who now lives in Medford, but then had a home on Peacevale Road, about one block from the health center’s present site.

“The abandoned businesses — block after block. That’s why I and others really doubted that we could do that much with it,” said Scott. “But he was extremely adept at using his political science skills in terms of getting grants. He’s almost a magician.”

Walczak and his team— including Linda, who was still at UMass but volunteered extra time for strategy sessions— met around a centuries-old table at the Blake House, Boston’s oldest standing house, where the couple lived for five years as caretakers. For a few years, the Blake House was the mailing address for the Codman Square Health Committee, raising eyebrows from the mailman, as Linda recalls.

Codman Square Health Center Incorporated: April 1975 ceremony. Pictured, l-r, State Rep. W. Paul White, City Councillor Larry DiCara, Doris Brown, John MacNeil, Bill Walczak, Secretary of State Paul Guzzi, Craig Wall, Mona Scantlebury, and Charles Murphy.By 1975, Walczak and the committee had fixed their sites on a potential home for the clinic: A mostly abandoned city library at the corner of Washington and Norfolk streets that had recently been vacated. Mayor Kevin White’s administration had retrofitted the space inside the library to house a satellite office of the city housing department, but Walczak argued that the city should make room for the fledgling center. The neighborhood largely agreed, fearful that the old brick landmark would —like so many other empty structures— go up in smoke. Walczak also found some allies among local residents who worked inside the city’s Boston Redevelopment Authority— young turks like Bob Rugo, John Coggeshall, and John Weis. But the mayor’s inner circle was cool to the idea and, according to O’Hara, soured on the health center model after a failed experiment on nearby Harvard Street.

Codman Square Health Center Incorporated: April 1975 ceremony. Pictured, l-r, State Rep. W. Paul White, City Councillor Larry DiCara, Doris Brown, John MacNeil, Bill Walczak, Secretary of State Paul Guzzi, Craig Wall, Mona Scantlebury, and Charles Murphy.By 1975, Walczak and the committee had fixed their sites on a potential home for the clinic: A mostly abandoned city library at the corner of Washington and Norfolk streets that had recently been vacated. Mayor Kevin White’s administration had retrofitted the space inside the library to house a satellite office of the city housing department, but Walczak argued that the city should make room for the fledgling center. The neighborhood largely agreed, fearful that the old brick landmark would —like so many other empty structures— go up in smoke. Walczak also found some allies among local residents who worked inside the city’s Boston Redevelopment Authority— young turks like Bob Rugo, John Coggeshall, and John Weis. But the mayor’s inner circle was cool to the idea and, according to O’Hara, soured on the health center model after a failed experiment on nearby Harvard Street.

“They were gun shy and when we approached them they were really reluctant to get involved in another failure,” O’Hara said.

But, with a contested mayoral election on the horizon in 1979, Walczak’s radical instincts kicked in and served the group very well. He planned to hold a press conference outside the old library and blast the incumbent mayor for ignoring the plight of the poor and the elderly. He and his team would shame White into acting on their plan.

It worked. A day after the press conference, the mayor caved and permitted the fledgling health committee to move into the library’s basement.

It’s one of the great ironies of the Codman story that Walczak — the group’s ring leader— missed that historic press conference. His father, a World War II veteran who had spent his life building Buick Wildcats — had suffered a massive coronary the day before. Bill raced home and said his goodbyes. His dad died the day that, in some respects, the Codman Square Health Center was born.

Soon after, Walczak was elected director of the newly-opened institution. It was a nice title, but there was a catch: He was also the receptionist, head nurse, dental assistant, maintenance man, and painter.

“That guy would have paint all over him whenever I’d go to see him,” says Seaborn Scott. “He would even plant the trees around the center and do small carpentry jobs.”

Thanks to the Carney Hospital and a Daughter of Charity leader who bought into Walczak’s ideas — Sr. Kathleen Natwin— the new clinic received funding to pay for an internist and a pediatrician to see patients in the basement.

“They were so far ahead of their time in working out these arrangements in low-income neighborhoods,” Walczak says of the Carney leadership of that era. “They set up this whole array of health centers. These are things that people are talking about doing today.”

Charlie O’Hara helped the center score state funds to pay for a dental clinic. Eventually, the city surrendered the upper floor of the old library — since restored and renamed the Great Hall— and the center began a pattern of expansion that continues to this day. In the 1980s, the center bought an old nursing home next door — using every penny it had assembled over the previous decade— and then secured mostly private funds to renovate it into the space it occupies today.

The constant throughout, everyone agrees, has been Walczak, whose passion for Codman Square, the health cause, and his adopted hometown remain intense.

O’Hara has seen Walczak change— but only a little. “He has mellowed. He’s more politically savvy than he was at that time. When he saw something going wrong, he wanted to set it right, right away, but there are a lot of things in government that aren’t fair.

“But his leadership ability and his tenacity and fervor for health care and that community-oriented attitude” all served him well, O’Hara concludes. “And he was very fair in his dealings – and terribly honest, almost to a fault. Those are the qualities I’ve always liked about him. He attracted people, too, and was very faithful and he seemed to be able to work with all types of people.”

Linda Walczak says her husband struggled mightily with the notion of leaving Codman Square for Carney Hospital last month, even though he’s confident that the team he has assembled — led by current chief operating officer Sandra Cotterell— is more than up to the challenge. “It’s funny. He’s known for change and innovation, but for him personally he doesn’t like to change things up too much,” she said.

Charlie O’Hara puts it a bit more colorfully: “I think he figured they’d carry him out in a box from the health center.”

Seaborn Scott is certain that the 56-year-old Walczak will make his mark at Carney, much as the 20-year-old New Jersey transplant did all those years ago.

“Bill is, to me, more than qualified to run a hospital. He knows the business and finance part of it. He knows doctors and dental care, the politics. He has really traveled that road,” Scott said. “As the poet Robert Frost said, ‘He took the road less traveled — and that has made all the difference.’ “

Villages:

Topics: