March 31, 2011

Dot Demos: Click for larger version.

Dot Demos: Click for larger version.

The face of the Dorchester community has gotten more diverse, and there are more of us living here, according to the 2010 Census data released March 20 and analyzed by the Reporter.

Already Boston’s largest neighborhood, Dorchester experienced a 1.9 percent rise in its population over the last decade to an estimated total of 134,496.

Mayor Thomas M. Menino claimed the growth is reflective of the overall Census figures for Boston. “That’s the trend in the city,” he said. “It’s not just new housing, it’s because people want to live here,” he added, while on his way out of a Dorchester Board of Trade luncheon at the Phillips Old Colony House on Tuesday. “It’s a place where they can raise their children, send their kid to a school near their home.”

The city’s official planning agency, the Boston Redevelopment Authority, arrived at a set of figures for Dorchester that differed greatly from the Reporter’s numbers: The BRA calculated a population of 91,982 for Dorchester and 36,480 for Mattapan. Those figures are based on maps of the city used by the BRA that transferred sections of Dorchester into both Roxbury and Mattapan, a controversial decision that has raised questions in all three neighborhoods. See related story.

The Reporter’s analysis of the Census numbers showed that Mattapan lost both residents and diversity. In the decade since 2000, the neighborhood lost more than seven percent of its population, including more than 500 white residents, a 32 percent decrease. The black population, which makes up more than three-quarters of Mattapan residents, also went down by nine percent, and the number of people who listed themselves as “two or more races” in 2000 was cut in half by 2010, to just over 600.

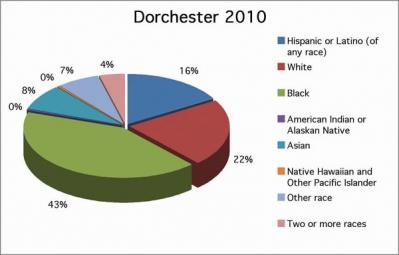

In terms of demographics, the greatest change in the Dorchester population is a 20.7 percent rise in Hispanic/Latino residents, and a 70 percent rise in people – 9,535 – who list their race as “other” – that is, they do not consider themselves black, white, Hispanic, Asian, Hawaiian, American Indian, or Alaskan native. Potentially less noticeable changes include the white population decreasing by 6.5 percent, a decrease in the black population by 5 percent, and an increase in the Asian population by a little more than 8 percent.

But the racial shifts are more subtle than they are earthshaking, said Dan Larner, director of community organization at St. Marks Area Main Streets.

Though the Hispanic population rose slightly, Larner said, the community has not changed much. “If it went from 14 to 30 percent, it would be noticeable,” Larner said. “The changes on those levels, I don’t think they’ll be perceptible on the streets.”

The array of races and countries of origin that now make up Dorchester presented an unlikely problem for Dorchester House, the community health center in Fields Corner. About a third of the center’s patients are Vietnamese, but people of Hispanic, Cape Verdean, Haitian, and other descents also walk through the door daily. The multitude of languages employed means signs marking anything from the bathrooms to the radiology department would have to include five languages to be useful.

“We had limited ourselves to translating the signage to only Vietnamese and Spanish, only because of amount of space it takes up,” said Ira Schlosser, the director of planning and community affairs.

Instead of ordering colossal signs or confusing non-English speaking patients, center officials decided to paint signs with universal icons instead of words and give patients a “cheat sheet” – a brochure that translates icons into English, Spanish, Vietnamese, Haitian Creole and Portuguese Creole. The translations will also be displayed on a large sign near the entrance.

Thomas Callahan, executive director for the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance, said his organization has considered altering its educational offerings to accommodate the rising Hispanic population.

“We’re definitely seeing more Latinos in Dorchester; there’s more of a need for [classes in Spanish],” Callahan said. “It’s something we are looking at – do we need to increase the number of Spanish classes we offer?”

State Rep. Marty Walsh, a Dorchester Democrat, attributed the figures to an increase in housing, as well as larger Hispanic and Vietnamese families moving into the area. The numbers also reflect a nationwide trend of an increase in Hispanic residents.

Walsh said the Boston area could also gain part of a state representative seat, a reversal from the city losing a representative seat during the last Census and redistricting effort. (The late Kevin Fitzgerald, who represented Jamaica Plain, decided to retire.)

“What happened ten years ago, I don’t see that happening,” Walsh said. “We certainly could gain part of one.”

Citywide, Boston as a whole grew by 4.8 percent, according to the Census data, and now boasts of being home to 617,594 – the highest population for the city since the 1970 Census. Demographically, the biggest increases were among Hispanic/Latino population (26.8 percent) and Asian population (24.6 percent). The white population fell by .4 percent, and the black population by 1.6 percent. Those who listed themselves as being of “two or more races” dropped from 18,174 in 2000 to below 15,000 in 2010. And those who described themselves as “some other race,” went up by almost a quarter, to now just over 10,000 individuals.

Bill Forry and Gintautas Dumcius contributed to this report.